How GIS Mitigates the Impact of Vacated Office Space

What Is the Doom Spiral?

One of the most damaging and lasting economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increase of unused and vacated office spaces. This has almost exclusively been driven by the immediate need for remote work, followed by the slow (some would say “glacial”) pace of return to work in the office. A Wall Street Journal report from a few months ago cited the number of remote work listings were beginning to “rapidly dwindle”. Regardless, this slow return to the office has caused economic downturns in areas that have a domino effect for local businesses, further hindering economic development efforts. This event is called a “doom spiral”.

First, if employees aren’t in the office, there is less foot traffic around neighboring businesses, such as restaurants, stores, and other service providers. CBRE, considered by many as a global leader in commercial real estate services, conducted a study of this effect noting a nearly 60% reduction in average foot traffic in business districts during the first two years of the pandemic. Less foot traffic leads to lower spending. Think of the lack of lunchtime and after-work visits to nearby restaurants and bars. Lower spending invariably leads to local business closures and downsizing.

Second, this excessive supply of unused and vacant office spaces puts considerable pressure on the local commercial real estate market. An Investopedia article in April 2023 noted that “Across the U.S., office vacancy rates averaged 16.9% at the end of the first quarter, up from the 12.4% average vacancy rate in the first quarter of 2020.” If the office space is vacant, it leads to a declining value of commercial real estate. This affects the owners and investors, as well as the banks that are holding the loans for these properties. This can lead to loan defaults, which leads to reduced property tax revenue, which leads to reduction in municipal services, and ultimately, economic stagnation.

How Can Cities Reverse This Trend?

The “simple” fix for this is for employers to require a return to office work. Currently, that’s a slow process, primarily because labor shortages give some people demanding remote work some temporary leverage. But planners and city leaders must be more proactive and long-range with their strategies. Dealing with vacant office space provides an opportunity to rethink land use in urban areas. In other words, if companies are not going to make full use of allocated space, how can cities promote changes in uses that meet the changing needs of its residents.

As stated many times in this space, the need for housing (both market and affordable) has not slowed nationally. Planners can look to vacant offices as space that can be repurposed for affordable housing. Buildings that are currently single purpose towards commercial or office use can be re-zoned to mixed use developments. This supports the concepts of economic mobility, whereby residents are within walking distance (or reasonable transit access) to jobs, services, healthcare, education, and so forth. Another option is to redefine the permitted types of commercial or office space that could be used. Instead of traditional office space, using the vacated areas for collaborative (or shared) workspaces or a small business incubator might be viable options. If this concept sounds vaguely like a type of zoning reform, that’s because it is exactly that. It is altering the zoning ordinance of a city to meet the modern needs of its residents. This kind of effort requires a geographic approach to planning.

GIS to the Rescue

We’ve highlighted the five facets of the geographic approach to planning here many times, and all of these apply to efforts to reverse the doom spiral of vacated office and commercial spaces.

- Understanding neighborhood characteristics. Where are demands for housing? Where is vacant office space and what are the demographics in the area? Would changes to the land use in these spaces address affordable housing and economic mobility issues?

- Deriving business intelligence from permitting. Where are we seeing the most demand for residential growth? What trends and patterns can we see over time that might identify a vacant office building as a viable (or non-viable) choice for repurposing? Where are the more disadvantaged locations that could benefit the most from impactful changes like this?

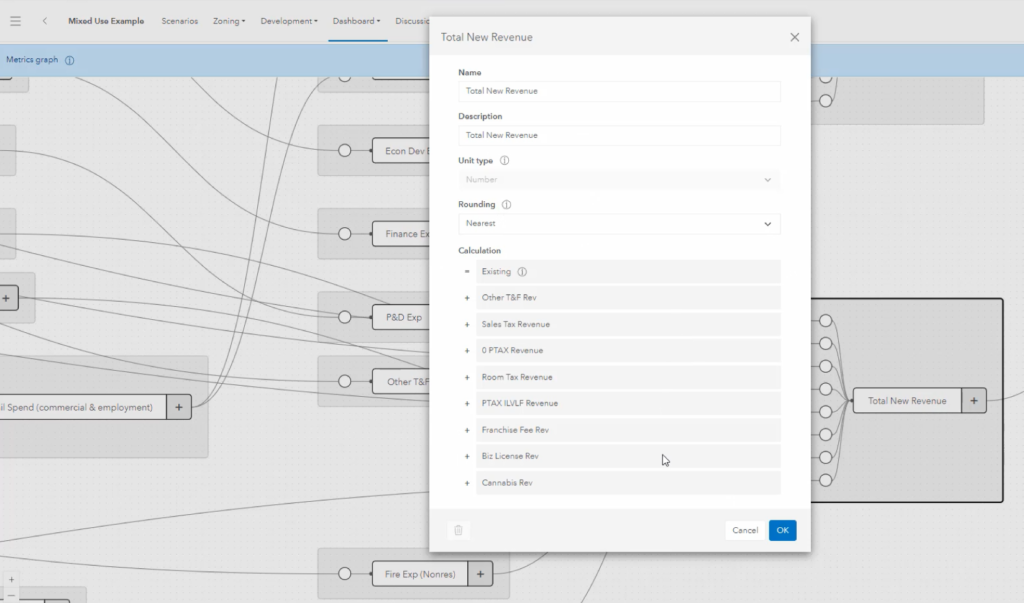

- Generating sustainable policies. What is a reasonable amount of office/commercial space that we could repurpose for viable uses? Would economic incentives be helpful in attracting a business incubator or a developer to design a mixed-use development in the space? What would be the impact on tax revenue in the area?

- Supporting civic inclusion. This kind of long-range planning cannot occur successfully in a vacuum. What do local residents think about these potential changes? What opportunities do developers see for this vacant space?

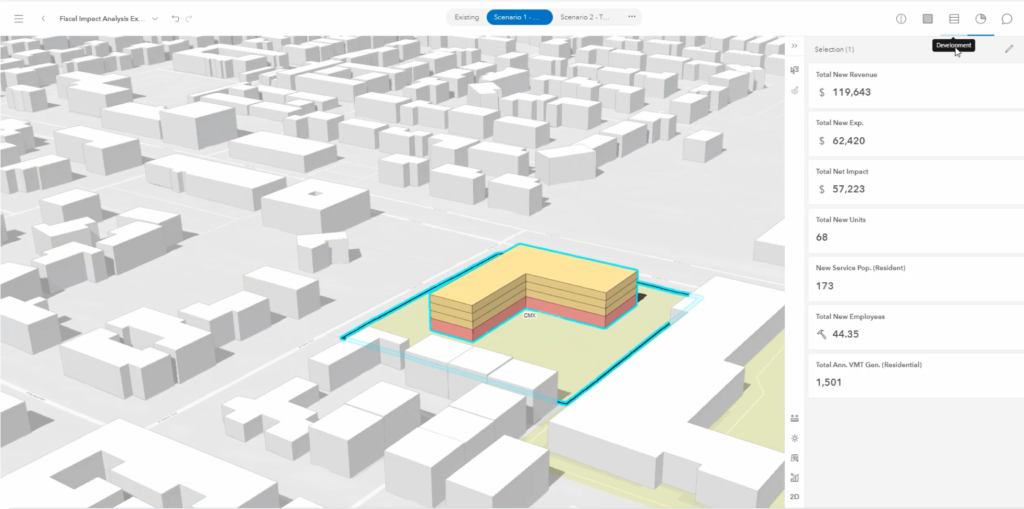

- Empowering scenario planning and design. What would a redesigned building look like if it were changed to higher-density housing? What would the fiscal impact of ensuring 10%, 20%, or 30% of the housing be designated as affordable? What if we change the property to mixed-use? What are the potential new developments that could occur around this project?

These are all questions that ArcGIS can answer. Location is at the core of all things planning-related. ArcGIS provides the platform for a timely data-driven approach to sustainable economic development, rather than one that is anecdotal. It helps establish buy-in from city leaders, planners, developers, and the public for ways to repurpose unused space to meet the needs of a community.

The economic doom spiral is a reality for many cities big and small. But more and more cities are looking to ArcGIS to counter this trend and design sustainable, thriving, and equitable projects and neighborhoods. In the coming months, we’ll have some relatable and repeatable stories about some of the projects that these cities have tackled.