Last weekend, I decided to step away from the computer for a while and go for a drive-in picturesque San Bernardino National Forest. Located just an hour east of Los Angeles, the series of mountain trails and campsites is one of the few remaining bastions of sparsely developed landscapes in Southern California. On my way into the forest, I was greeted by an American icon—I’m talking, of course, about Smokey Bear. For decades, Smokey has stood vigil at the entrance of every national park and forest, reminding visitors to be wary of accidentally starting forest fires. Like many of you reading this, I’ve been a huge fan since childhood!

In Southern California, where I’m from, Smokey is a particularly powerful figure. Wildfire exposure is just a fact of life, something that’s always in the back of residents’ minds. In 2020 alone, there’ve been about three too-close-for-comfort moments in my family. That was certainly the case on this particular drive, because something about Smokey stood out to me in a new way.

Smokey is almost always accompanied by a sign indicating the current potential for fire danger. The scale—which typically ascends from low to moderate to high, finally ending at extreme—offers a glimpse into the conditions that lead to most wildfires. When I was looking at the sign that day, I began to wonder whether this particular way of thinking about wildfires—or any peril, for that matter—effectively communicates the actual danger as it relates to the unique attributes of an area, or whether it is oversimplified.

You may have noticed something, especially if you live in the Southwest: it seems like the wildfire danger is always high. Also, it’s not uncommon for a place like Mount Rainer National Park, in Washington State, to have the same categorical rating as a place like San Bernardino National Forest, despite the latter and its surrounding area having statistically more frequent and severe wildfires year after year. These two points are oddly linked.

Don’t get me wrong, I completely understand that the purpose of Smokey and the sign in question is to serve as a public service announcement to visitors, and this categorization is a valuable way of communicating those dangers to increase public awareness. Nonetheless, this reflects a troubling trend that I’ve seen in the insurance industry: oversimplified or overgeneralized risk scores being provided to decision-makers without valuable context.

Clarity versus Simplicity

Before coming to work at Esri nearly five years ago, I graduated with distinction from a government-sponsored master’s program around national security. It was in that program that I was introduced to formalized intelligence methodology and the field of metacognition, which is the understanding of how someone’s way of thinking influences their perceptions and ultimately the decision-making process. This is where I came across the notion of executives and analysts alike having categorical biases.

Picture an intelligence analyst briefing a key decision-maker on a high-stakes situation (my go-to is always the scenario in the movie Independence Day). After the analyst presents their briefing, the decision-maker asks how sure the respective agency is in its assessment. In many scenarios, you’d expect to hear the analyst share some type of category such as having low, medium, or high confidence in the assessment—and therein lies the problem. I experienced firsthand how these categories actually don’t add value but lead to confusion. To quote a line from the movie The Princess Bride, “You keep using that word; I don’t think it means what you think it means.”

What does the term medium confidence actually mean? When presented with three categories (or four, in the case of Mr. Smokey), the decision-maker should logically divide those categories up evenly based on 100 percent. This would mean that medium confidence would be 33–66 percent. However, since this is open to interpretation, some decision-makers may, in fact, assess medium confidence to be 70–85 percent; this would mean that low confidence is 0–69 percent, and high is 86 percent and above. This is because of one type of categorical interpretation being used to interpret another.

In this particular example, the decision-maker is using academic grading scales to interpret the confidence level because of a qualitative understanding based on what low, medium, and high mean to that person. Low is often associated with something bad or failing—imagine D+ and below. Medium can be fairly good but not necessarily desired, like C- through B. Finally, high is reserved for the best, from a B+ to the top mark. This categorical bias essentially leads to decision-makers coming to drastically different conclusions from those of their analysts, based on subjective experiences and unconscious biases. Maybe medium isn’t that good—or do I mean bad?

The issue is not that Smokey Bear uses a categorical rating to assess the fire potential. The problem is that decision-makers have become so accustomed to this way of thinking that deep contextual meaning is completely lost, leading to a higher likelihood of miscommunication. When it comes to complex situations like assessing wildfire risk to a portfolio or making underwriting decisions, decision-makers need clarity, not simplicity.

The Move toward Dynamic Risk Accumulation

So then, why is it that two federally managed lands, like Mount Rainer and San Bernardino, can have the same wildfire risk rating despite having significantly different attributes and relative exposure? Why is it that areas in California are deemed constantly at high risk despite some seasonal conditions that make wildfires statistically unlikely? The answers to both of these questions are the result of categorizing the risks based on static risk models, meaning varying interpretations based on different situations.

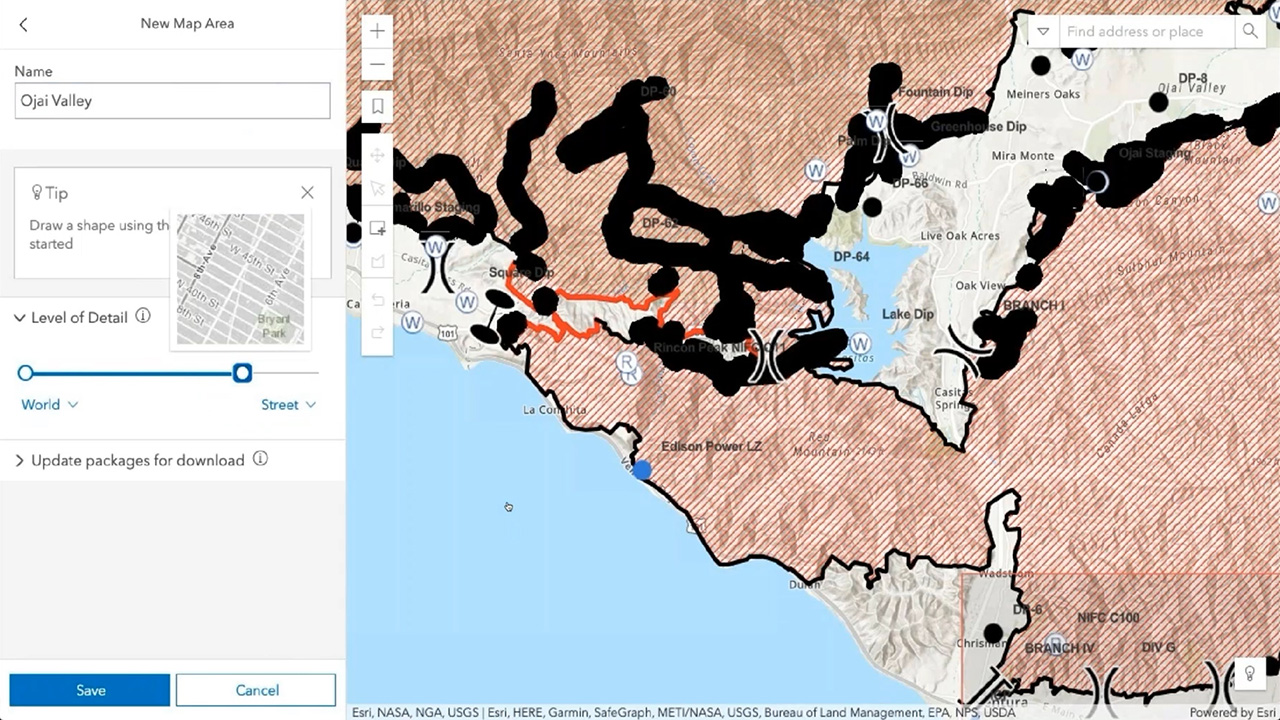

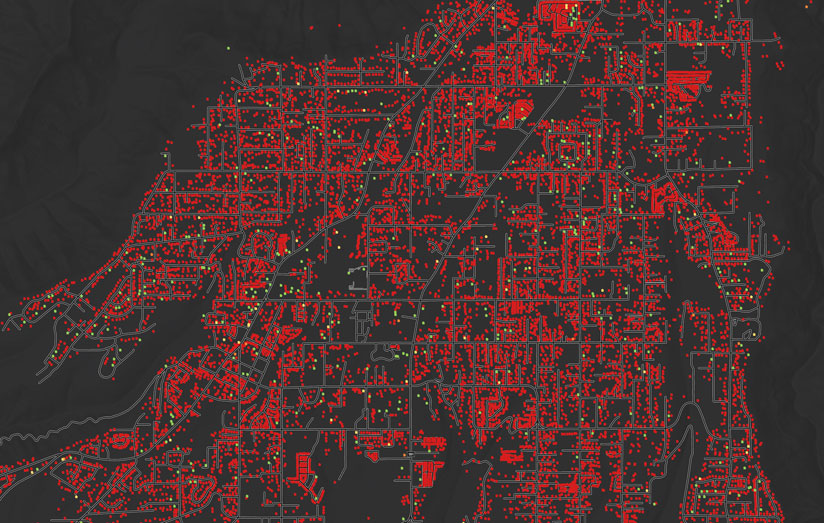

Insurance companies don’t have to be stuck with these static risk models. Recent advancements in 4G and 5G technology have led to significant innovations in risk accumulation that fundamentally alter the conversation around risks and perils. By using location intelligence as a foundation for core spatial analyses, many of the insurance customers I work with are ingesting large quantities of disparate datasets to create more accurate models that clearly communicate the real-time exposure of an area to a specific peril.

Location intelligence empowers risk and exposure teams to combine real-time data—from weather forecast, humidity, wind speed, sun intensity, and vegetation reports—with information on static conditions—like soil composition, forest density, elevation, and wind dynamics—to create a new class of risk models that are kinetic. Think of these living models as digital twins of the natural world, bringing clarity to complex situations.

Kinetic risk models provide iterative updates based on several key variables that determine the relative exposure, taking into account oftentimes missed variables—for instance, whether higher-than-usual rainfall this year has created more ground brush. Instead of seeing San Bernardino National Forest as always being at high risk, analysts within the insurance industry can unleash the full potential of their data to see how statistically likely a wildfire is, based on historic trends. By shifting the narrative, the conversation moves from saying, “This area is at high risk,” to making assessments such as, “Based on current conditions, this area is 30 percent more likely than usual to experience a wildfire and 60 percent more likely to conform to the average exposure in the United States.”

As perils like wildfires, hurricanes, and floods continue to grow in both frequency and severity, insurance companies will need to embrace this kinetic-data approach to stand up living maps that accurately represent the situation on the ground and promote statistically sound decision-making for underwriting, pricing, and catastrophe response. The alternative is to roll the dice and continue with categories that can lead to costly mistakes.