I recently sat down with Diana Yassanye and Dr. Ranelle Brew, co-founders of Parasol Health Consulting, to discuss the transformative potential of funded public-private partnerships for public health. Our conversation delves into the nuances of collaboration, the value of data, and the role of geographic information systems (GIS) in addressing critical public health challenges. Before I share our conversation, let me introduce Diana, Ranelle and their organization.

Parasol Health Consulting, LLC is a strategic consulting firm. Co-founder, Diana Yassanye, is the former Public-Private Partnerships Lead for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and co-founder, Dr. Ranelle Brew, founded the accredited Master of Public Health program at Grand Valley State University. Their company provides innovative scientific and technical solutions to advance national priorities in science, education, security, and health. Through teams of specialized subject matter experts, Parasol Health Consulting works with federal, state, local, academic, research, and commercial customers to advance public health priorities and serve public interests.

Diana: Este, at the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) Preparedness Summit in April 2023, colleagues and I discussed public-private partnerships. While the session emphasized non-monetary collaborations, you approached me afterward and highlighted the importance of funded partnerships in extending public health knowledge and preparedness. Can you elaborate on this?

Este: Absolutely, Diana. Funded partnerships often carry a stigma of being purely transactional, which can hinder trust. Yet, these relationships can be incredibly impactful when approached as true collaborations. Many private sector organizations employ industry experts who bring invaluable knowledge and serve as trusted advisors. While financial exchange is involved, it’s essential to remember we’re all working toward shared goals of improving health outcomes. How does that happen? My view is that public-private partnerships, at their best, bring together the expertise of public health professionals, who understand the specific challenges and objectives, and private sector advisors, who contribute tools, methods, and analytics tailored to address those needs. This is when innovative solutions emerge.

Ranelle: In schools of public health, we discuss the importance of large data sets to inform public health efforts and overall community health assessments. Can you share examples of non-emergency data that helps track community health and enhance decision-making for public health initiatives?

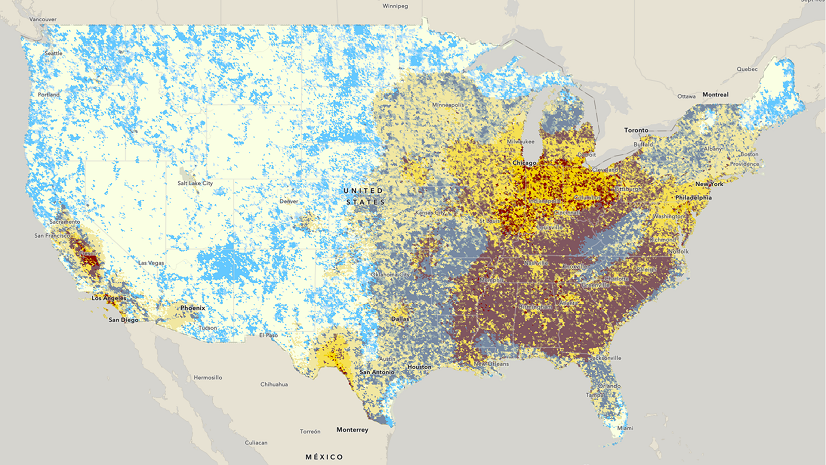

Este: Certainly. Non-emergency datasets are critical for proactive public health efforts, especially when they are geo-enabled, meaning they are ready for mapping and visualization. We believe that public health organizations should systematically collect and maintain these key datasets for ongoing needs so that they are available when an emergency happens (we built a lesson on how to do this – see it here). Here are some examples of what I consider foundational data:

- Demographics (race, ethnicity, age groups, income, education, and so on)

- Labor statistics (unemployment and employment)

- Social vulnerabilities (transportation access, health insurance coverage, poverty, disabilities, predominant language spoken, access to broadband, and more)

- Healthcare facilities (hospitals, urgent cares, nursing homes, etc.)

- Other facilities (schools, day cares, shelters, public health departments and so on).

- Transportation networks and infrastructure (roads, helicopter landing zones, public transit stations, railways, ports, airports, etc.)

The span of non-emergency datasets relevant to health is broad and goes well beyond what I’ve noted. Some great places to get at most of these datasets include Esri’s Living Atlas of the World (free open data from authoritative sources) and Homeland Infrastructure Foundation Level Data (HIFLD open data site).

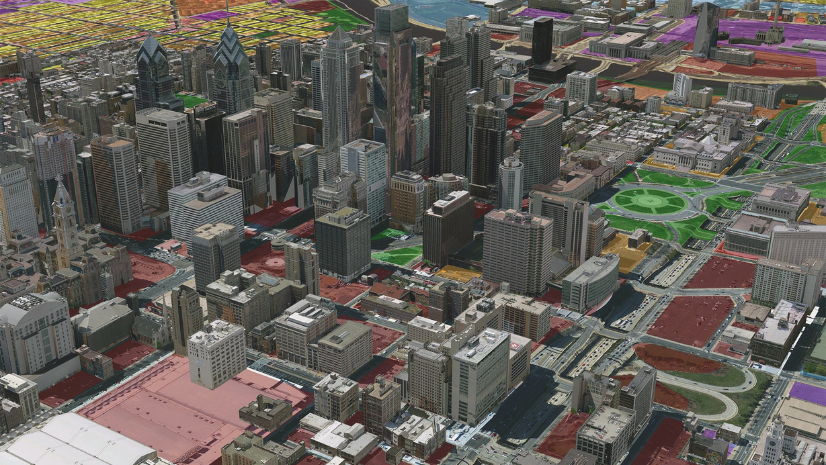

I should also mention that health departments can geo-enable (i.e., include a mappable location) their own data from spreadsheets or other systems, allowing for more detailed analysis and visualization. And for certain tasks, like Community Health Assessments, data needs to be collected efficiently. We built a Community Health Assessment solution that facilitates household-level surveys (using the CASPER methodology), preloaded with the most common questions. It’s customizable and empowers public health departments to combine locally collected data with broader datasets to identify health trends and prioritize interventions.

Diana: Coming from the government, I was struck by the attitudes towards all for-profit companies. Even after I facilitated the establishment of the agency-wide conflict of interest review panel for public-private partnerships, there was still a lot of hesitancy to collaborate with the private sector. In reality, the private sector and the public sector need one another and already do collaborate in transparent and supportive ways all of the time. Can you share a specific example of how Esri has collaborated with public health agencies to address pressing challenges?

Este: Transparency and shared purpose are key to successful collaborations. During the pandemic, we collaborated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) by supporting an effort to help state public health departments standardize their COVID-19 dashboards. This would help states and the CDC respond more effectively (learn more here). Later in the pandemic we collaborated with CDC again on a project intended to improve vaccine confidence (see press release). That work has now evolved into their GISVaxView application that goes beyond COVID-19 vaccination to include influenza and RSV vaccination coverage as well.

Another example is our collaboration with health-focused trade associations. We co-create educational materials (here’s an example about health equity created with NACCHO), ensuring members have the tools and knowledge to leverage GIS for public health challenges. Even in sales relationships, we see ourselves as co-creators, working alongside public health agencies to solve pressing issues.

Ranelle: Workforce development is a focus for Parasol Consulting. How do you see university program collaboration, such as schools of Public Health and geography departments working together? Do you think there are opportunities within schools of public health to build out the next generation of the health workforce with ArcGIS training and skill building?

Este: The opportunities are immense. The pandemic revealed gaps in public health informatics training, leading to initiatives like the Office of the National Coordinator’s (ONC) grant program for public health informatics. Through this program, Esri collaborates with the California Consortium for Public Health Informatics and Technology (CCPHIT, one of the ONC grantees), providing GIS training to students and professionals. I’ve personally taught nearly 400 learners in the internship program.

Additionally, we’ve developed a free Health GIS Curriculum (available here), tailored to health organization needs. It features real-world use cases and offers flexible lessons ranging from 15 minutes to two hours. This resource, available in seven languages, complements other learning opportunities through the Esri Academy and publications like GIS Jump Start for Health Professionals, written by a Carnegie Mellon professor and published by Esri. These collaborations ensure the next generation is equipped with the skills needed to harness GIS for impactful health initiatives.

Diana: I’ve worked on public health responses since 2005. Having visualizations of where vulnerable populations were, disease prevalence, environmental factors impacting populations, and available resources were (and still are!) crucial tools to inform public health and a “whole community response,” especially when public health officials have limited resources and a clear mission to support the entire population. I’d love to hear one of your favorite anecdotes about Esri’s collaboration during a public health emergency response.

Este: One standout example comes from early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Health departments urgently needed data on hospital bed capacity, including ICU and ventilator availability. We facilitated a partnership with Definitive Healthcare, a commercial health data provider, to create a freely available, geo-enabled dataset. Public health officials used this to visualize capacity constraints and plan surge responses, such as setting up temporary hospitals. This effort exemplified a private-private-public partnership where everyone’s strengths contributed to the greater good.

Ranelle: As a timely example, with the California Wildfires impacting our communities, I often think of social determinants of health and the contextual/environmental factors that impact a community and individuals. For example, how childcare options, transportation, and even clean air and water can all factor into the health of a population. Can you describe a hypothetical scenario where public health officials and Esri could work together to review multiple factors for population health?

Este: Absolutely. In the context of California wildfires, public health officials could use GIS to evaluate the compounded effects of environmental and social factors. For instance, GIS can help visualize near real-time air quality data to identify areas where residents face prolonged exposure to unhealthy air from wildfire smoke (learn more about street-level air quality data here). By overlaying this information with data on vulnerable populations—such as children, elderly individuals, those with pre-existing health conditions or electricity dependency (learn about HHS Empower Program)—officials can pinpoint communities most in need of interventions.

Beyond air quality, GIS can assess transportation accessibility, ensuring evacuation routes are viable and identify areas where additional shelters may be necessary. Public health officials can also integrate datasets on childcare availability and water quality to address broader health impacts. Harris County, Texas used GIS to share boil water alerts after Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Tools like Esri’s wildfire dashboards (listed below) and the Social Equity Analysis solution help operationalize these insights, enabling targeted resource allocation and effective community support in the face of environmental challenges.

Palisades Fire Damage Inspection Dashboard

Palisades Fire Structure Status Instant App

Eaton Fire Damage Inspection Dashboard

Eaton Fire Structure Status Instant App

Palisades Damage Inspection (DINS) layer

Eaton Damage Inspection (DINS) layer

Diana and Ranelle: Thank you, Este, for sharing these insights. It’s clear that public-private partnerships, when approached collaboratively, hold immense potential for advancing public health.

Este: Thank you both for the opportunity. Partnerships like this conversation itself exemplify how collaboration can lead to meaningful progress. Together, we can address public health challenges with innovative tools and collective expertise.