Geography is Destiny

I recently listened to a series of podcasts about the upcoming redistricting process. The host of the podcasts reviewed a collection of stories examining the many legal battles concerning redistricting over the past several years. Eventually, the host used a phrase that grabbed my attention. While describing the winners and losers in redistricting, he said, “Geography is destiny.” Isn’t that fitting? Credited to Napoleon and his geopolitics theories, he supposedly said this phrase just before his army invaded Russia. Hmmm, we all remember how that turned out. All the same, I think the phrase — as applied to redistricting — is a good one. Isn’t everything about redistricting a geographic problem?

4th Grade Civics Hasn’t Gotten More Interesting

In truth, the process of redistricting is somewhat straight-forward but based on tremendously detailed data. On April 1st of 2021, the Census Bureau will release their Public Law data (P.L. 94-171) files. These files contain the population data at the Census Block level with 288 race tabulations; this is where redistricting becomes both tedious and laborious. The State of Maryland, alone, has over 145,000 Census Blocks that are collected into eight, near equal, congressional districts, 47 state Senate districts, and 141 House districts. Added to this, the process is filled with procedural rules that differ based on each state’s constitutional requirements and 40-years of case law. The process can be mind-numbing.

Re·dis·trict (present participle)

1. To divide or organize (an area) into new political districts: See Gerrymander

Redistricting, in and of itself, is not a nefarious process. Still, its history is filled with examples of people – read: political parties – using the process for gaming the system for their advantage. A quick read of Wikipedia provides a little perspective. Four-times as much text is dedicated to describing the gaming of the process — Gerrymandering — than defining the process of redistricting itself.

Mention the word “redistricting” in conversation at any social setting and talk of “gerrymandering” will soon follow. It is almost like the word has a direct line to our brain’s fear center, like a fear of snakes or frogs…

Back to the Podcasts

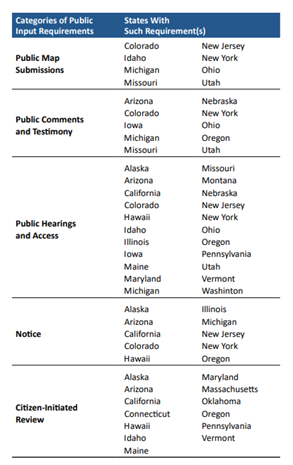

Let me distill these ideas covered in this podcast to a single thought. Over the last two years, over 28 legislative bills focused on redistricting addressed the public’s wants and desires to lessen the excesses of redistricting and increase the public’s ability to weigh into the process, themselves. The bills run the gamut from seeing the results of proposed plans before their passage, to removing all elected officials from the process, to establishing a ‘non-partisan’ body. This spectrum falls neatly into five groups; providing notice about meetings and the plans they propose, public access to hearings, the ability to provide public comments and testimony, citizen-initiated review of proposed plans, to the power of citizens to provide public map submissions.

If one steps back and considers this legislative trend, the obvious first question is, why? Redistricting has always been a part of U.S. civics, but it has never really been that important a topic. Redistricting has always been one of those civic processes that we learn about in school, but only briefly. For example, my son’s high school social studies textbook contained a single paragraph, less than 100-words, describing redistricting. It had three paragraphs, well over 700-words with two pictures, discussing Gerrymandering. But there it is, that word Gerrymander, again.

The Only Thing That Can Kill a Gerrymander is Sunlight

To a great extent, when we see convoluted lines and odd-shaped districts, we sense that something is wrong, but is that correct? The Civil Rights Act of 1964 did much to enable fairness in representation by protecting communities of interest and enabling the “carving-out” of districts that could support candidates more represented of their communities. When collecting people into districts, whether you are carving-out a community of interest or a political territory, it is nearly impossible to tell the difference after the fact. As humans, when we see things that should be somewhat straight-forward but look odd and convoluted, we get suspicious. Add this new suspicion to an already declining trust in our government institutions, and the word Gerrymander pops to mind.

This is Where Transparency Enters the Conversation

The idea that the public should be provided some level of participation is not new. Over 42 states have incorporated some level of participation into their redistricting process in their constitutions, and as I said above, 28 states did this in the last two years.

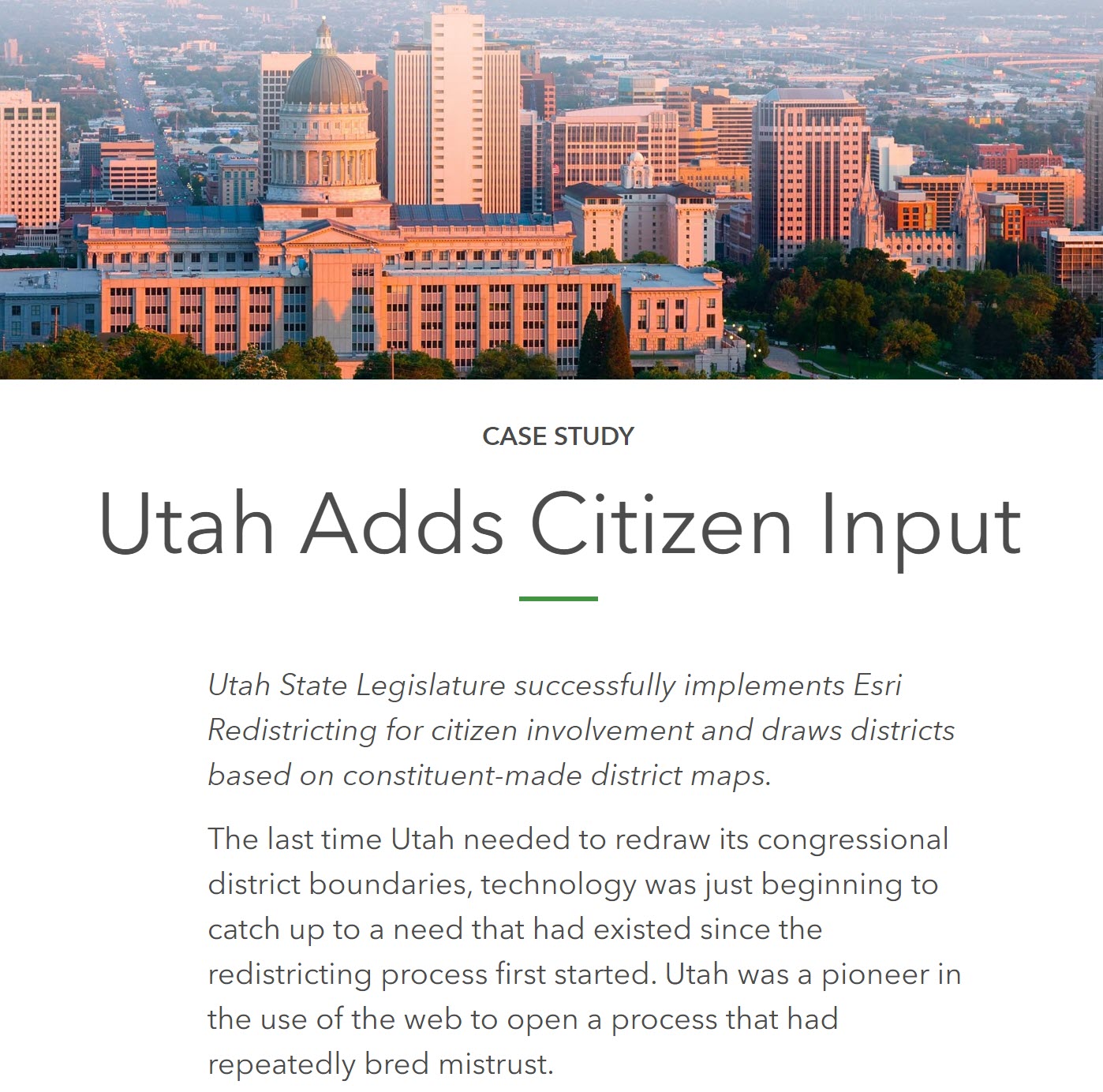

The state of GIS technology is such that it is feasible for a community to deliver Census data and GIS tools used in redistricting and provide public access to the process. As data-heavy and computationally complex the redistricting process can be, it is possible to deliver the data and the necessary tools along with an intuitive interface, both to the professionals and the public.

If transparency and public engagement are important elements in your community, I encourage you to watch Esri’s recent webinar recording and learn how our complete software solution can make the redistricting process easier for you.