Have you ever taken a survey that made you feel confused, or even frustrated? Or have you given a survey that respondents ghosted halfway?

Survey participation is a crucial part of success with surveys. Yet survey design experts cite sensitivity to the information provided as a common reason for non-response. Survey ethics is a way to increase trust by being sensitive to information which respondents share. For example, ensuring respondent privacy and confidentiality can help build trust with your respondents. By incorporating ethics in both recruitment and design, completion rates can improve while helping everyone do the right thing.

First, do no harm

A good place to start are the Human Subjects Research requirements outlined for federally-funded research, which are followed by many other research organizations. At their core, these guidelines can be paraphrased as two golden rules:

- The benefits/knowledge to be gained must outweigh risks (and adequacy of protection against risks). For example, ensuring respondent privacy and confidentiality can help build trust with your respondents.

- Survey respondents should be informed of risks and must voluntarily consent to participating. For example, ensuring respondent privacy and confidentiality can help build trust with your respondents. Informed consent can also entail what data is being collected, stored, and used.

In other words, survey participation should be voluntary and there should be a stated benefit for the respondents. Other professional organizations have their own ethics guidelines, such as the National Association of the Practice of Anthropology, and the American Association of Geographers.

Recruiting respondents

Recruiting voluntary participants can be challenging, but not impossible. The first step in ethical surveying is making sure that you are reaching out to the people who can truly benefit. Some issues to carefully consider are:

- Representation: Are your survey respondents representative? Your pool of participants should be representative of the larger population you are trying to learn about.

- Selection Bias: Has your pool of respondents been sampled to avoid selection bias? For example, if you are posting the survey’s QR code in libraries, you might overrepresent from those who frequent libraries. You also might get overrepresentation from those who have a phone that can scan a QR code.

- Correct Sample: Are you surveying the wrong people? If you’re recruiting through a clinic or a school, but you’re interested in underserved populations, you might be missing people.

- Compensation: Is compensation appropriate? If this survey is going to take some time to fill out, or if you’re surveying people for whom time is scarce, you might consider compensating respondents for their time. Examples could include being entered into a raffle for a gift card, a digital download of some e-book or other information product, or a discount to a product you offer. (Offer too much and it can be perceived as coercive.)

- Trust Building: If your survey is sensitive in nature, how will you gain trust? If answering your questions could trigger painful memories, will you provide a number to call such as a domestic violence hotline, or HIV hotline?

Survey design

Another important aspect of ethical surveying is ensuring the validity of the survey design. Wording and ordering of questions is important. Some examples of how this can go wrong are listed below:

- Specificity: “Do you like fried chicken?” is not the same as “Do you like KFC?” Personally, I love to eat fried chicken from a local BBQ restaurant by my apartment, but I actually do not like KFC. If you ask me, “Do you like fried chicken” and I respond “yes,” it would be false to conclude that I like KFC. Don’t overestimate the insights that you’re actually getting from your respondents.

- Loaded Meanings: Generational, gender, and cultural differences all factor in to how people interpret and respond to survey questions. For example, Americans are more likely than other populations to rate themselves “above average” for things like intelligence, health, driving ability, and so on, and men more likely to do so than women.

- Regional Assumptions/Biases: Geographical/regional differences can also play into different interpretations of questions. A question such as “What do you like to do on snow days?” won’t make much sense to people in warmer areas who haven’t experienced snow days.

- Question order: Psychologists often talk about priming as a phenomenon that can affect behavior, in this case, survey response. Priming is when current actions are influenced by very recent information. For example, if a school is interviewing a group of parents and places a question such as “What is the most pressing issue facing our school today?” right before “How well do you think our school principal is doing?,” respondents will be primed to think of the principal’s response to the issue they just chose right before. Early items in your survey could have an effect on later responses.

- Testing and Translation: Testing and getting translation right can take some care. Survey123 surveys can be translated into any language, and can even be configured to support multilingual surveys. See how this Taylor Shellfish Farms configured a survey in both Spanish and Khmer so that their farmworkers from Latin America and Cambodia were better able to respond to their Farm Debris Monitoring Survey.

Asking sensitive questions

Some factors that can undermine question sensitivity are social desirability bias, or virtue signaling. For example, when asking about gambling habits or activities, it may trigger defensive responses such as “Of course I don’t gamble!” or “Me, smoke? Goodness no!” There are ways to ask these types of questions that improves the overall response rate, and the quality of responses such as:

- Be as specific as possible when defining sensitive terms. Does gambling just mean trips to casinos, or does it include lotto ticket purchases and fantasy sports leagues? What about church or school raffles as fundraisers?

- Instead of asking, “Do you gamble?” simply assume people do, and ask, “How many times have you gambled in the past (specific time period)?” Be sure to provide a none/zero option.

- Consider making sensitive questions optional. This might cause this question’s response rate to decrease, but it could help to decrease people leaving your survey altogether.

Configure these survey questions

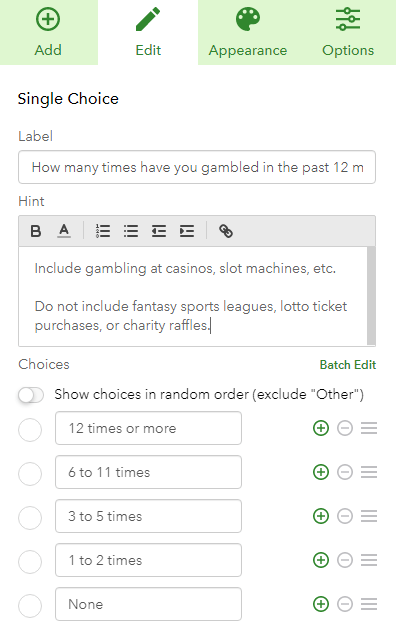

Step 1. Add a Single Choice question. Then the configuration options will appear.

Step 2. Type in the direct, timebound question in the Label, and any specific definitions in the Hint. Be sure to include a zero/none option.

Notice I listed the choices in decreasing order. I did this deliberately so as to prime people to see 12+ times as the initial point of reference, and subconsciously think, “oh, I guess I don’t gamble that much, I can answer honestly.”

I can preview my new question in my survey:

You’ll notice that there is no red star at the end of this question, indicating that it is optional (not required). This means that my respondents will be able to advance to the next question without submitting an answer should they choose to do so.

Order randomization

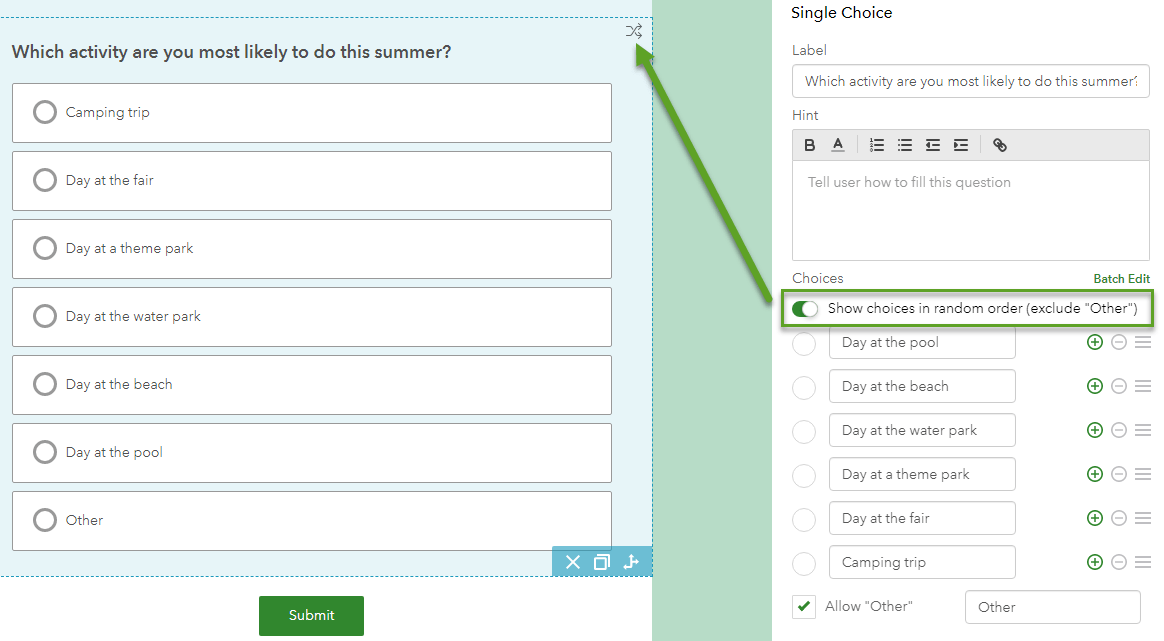

Similar to question order affecting responses, choice order can also bias results, as people tend to choose the first choice they agree with. If you have a survey question with choices that are not in a natural order, for instance, a non-ordered list of options about summer activities, consider randomizing the question options. When creating your survey, simply toggle on the “Show choices in random order” option, and you will see an icon of two intersecting arrows appear at the top of your question.

Pro tip: Consider doing a pilot test of your question in which half the respondents get a randomized list of choices, and half get the list in the same order. Compare the results and see if people in the non-randomized group are more likely to choose options higher up in the list.

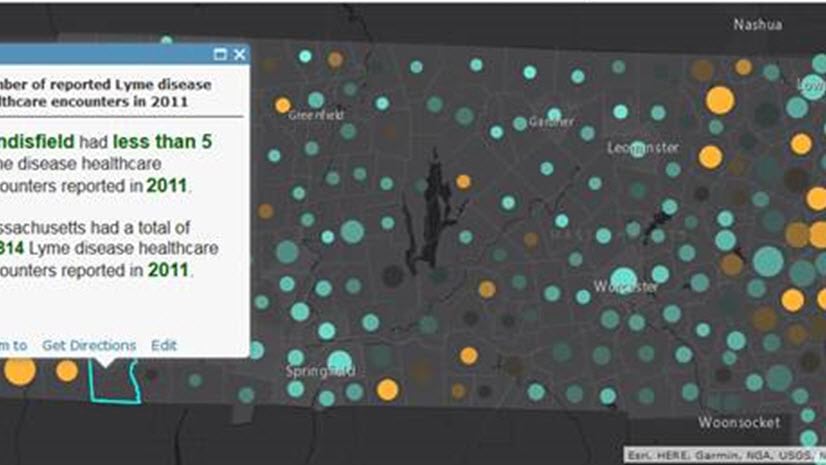

Presenting results while protecting privacy

Privacy and confidentiality requirements are very real, because geography is possibly the easiest way to identify someone. Even if someone’s name or address is not available, individuals might be able to be identified if they have unique responses to the survey, especially when responses to multiple survey questions are combined. For example, a certain neighborhood might only have one same-sex couple household with a child, only one widow who drives an electric vehicle, or only one 25-year-old female who is divorced. Depending on the survey topics and questions, I might be able to learn all about that person’s employment and earnings, medical information, and more.

When presenting your survey results, you may have to suppress low counts so that viewers of your public data and maps only see something like “3 or fewer” rather than the specific number. Another option could be to aggregate your survey points up to coarser levels of geography so as to protect respondents’ confidentiality, such as census tracts instead of block groups, or coarser categories, such as ages 18 to 34 rather than 18 to 24.

Some data visualizations in Survey123 are only enabled once a specific number of respondents complete the survey, such as the Word Cloud. A Word Cloud is a great way to visualize responses to open-ended/qualitative survey items, and requires a minimum of 20 respondents to appear.

If your respondents are likely to have an ArcGIS Online account, consider including a note to encourage respondents to sign out of ArcGIS Online before starting the survey to ensure anonymity, as Survey123 automatically captures information from ArcGIS Online accounts.

Additional resources for learning more

Survey123 resources

Have you ran a survey in which you incorporated some of these considerations? Share your work, or browse through the work of others, and exchange questions and ideas with the Survey123 user community.

Qualitative GIS resources

Article Discussion: