To me, what can be scaled up here is the idea of being really honest about what’s possible [in environmental conservation] and what works for local people. I think ArcGIS StoryMaps has been a really good medium to explore that complexity.

What do a household name in the world of guitar manufacturing and a central African sustainable development initiative have in common? It’s understandable if your first instinct is to answer that with “not very much.” Yet, since 2016, Taylor Guitars and the Congo Basin Institute (CBI) at UCLA have been engaged in an innovative partnership in rural Cameroon. To date, they have planted over 40,000 ebony trees and 20,000 fruit trees while fostering local, community-based development. And together, in 2024, they used ArcGIS StoryMaps to put together a report summarizing the project’s goals, progress, successes, and future.

Virginia Zaunbrecher, the Managing Director of the CBI, and Scott Paul, the Director of Sustainability for Taylor Guitars, sat down with Esri’s StoryMaps team to provide a peek behind the curtain at their ongoing collaboration on the Ebony Project.

Q: Can you each talk about your backgrounds and how you came to be where you are today?

Virginia: I have an undergrad in molecular biology and history, and then I went to law school, where I focused on the intersection between science and policy. After one year as a corporate lawyer, I spent five years in international development, mostly working with communities on food security, agriculture, health, water, and sanitation. I moved to academia a little over a decade ago, and I really like bringing together the three things that are part of my background: science, policy, and what I call “practice,” which is what communities on the ground are doing on a day-to-day basis.

Scott: I have a similarly nomadic background. Most of my career has been in environmental policy and advocacy. I spent fourteen years at Greenpeace, worked at the White House, and spent a lot of time following United Nations forest policy. I befriended [Taylor Guitars co-founder and president] Bob Taylor through some work Greenpeace was doing in Alaska, and some years later he offered me a job as Sustainability Director at Taylor Guitars, a position that I believe is wholly unique in musical instrument manufacturing.

Q: What led Taylor to become interested in sourcing ebony from the Congo Basin, and how did the CBI get involved?

Scott: Ebony has always been very important for stringed musical instruments because of its exceptional durability, smooth surface, and aesthetic appeal. Taylor has been using ebony for its fretboards and bridges since 1974. In 2011, we had the opportunity to purchase an ebony mill in Cameroon, and a couple years into [owning] it, Bob Taylor started asking some seemingly very basic questions: How much ebony is there? How does it reproduce? No one seemed to really know. Bob’s original thought was “let’s develop a planting program” to give back to a resource that has been supporting our industry for over a century. And then we met UCLA.

Virginia: The matchmaking was done by the U.S. embassy in Cameroon. The ambassador at the time told Bob Taylor, “you own this ebony mill, you need to meet this professor — Dr. Tom Smith from UCLA — who’s been doing research in the area for thirty years.” They met under a flagpole and, by all accounts, hit it off. They formed the kernel of the idea that would become the Ebony Project and shook hands under that flagpole.

Scott: [Dr. Smith] convinced us that to successfully plant, we need to understand some basic ecological underpinnings behind the species, so we added that component. And then “Dr. Zac” [Tchoudjeu], an agroforestry expert, got involved and persuaded us that to be successful working at a village level, where food security is a huge issue, that we should also plant fruit trees. Dr. Zac’s life work has been to identify the fruit trees that are most desired by different communities across the Congo Basin. So we added that, too. Put it all together, and that’s the Ebony Project.

Q: How has the somewhat unorthodox partnership behind the Ebony Project been an advantage in the project’s success?

Virginia: I often conceptualize it as Bob [Taylor] and Taylor Guitars being investors at the high risk stage, which allowed us to work out a lot of kinks [that other funders may not have].

For example, in order to plant a lot of ebony trees, you have to grow a lot of ebony saplings. Early on, we were excited about the possibility of tissue culture as a way to grow ebony at scale. But after a couple of years of trying it, we kept running into technical hurdles, and it turns out it’s exceptionally hard to reproduce tropical hardwoods successfully from tissue culture. We ultimately took an approach that sounded crazy in the beginning, which was finding ebony trees in the wild and collecting thousands of seeds from them every year.

Scott: I remember UCLA coming to us, saying “I know we promised you tissue culture and we really tried. It’s just not working but we now know that we can get the numbers through seeds” and we were like “Okay, that’s cool. If that’s the way to go, no worries. You tried, you failed, you learned. We’re moving on.”

[The project has had] a business startup mentality, which Virginia confessed to me she’d never experienced in a funder before. Traditionally, multi-year projects like this establish goals and milestones and criteria at the beginning of a project and must be adhered to, even if you later realize the idea was slightly flawed, or you learned something new along the way.

Another example [of this flexible approach] is, we were told that plants would be grown in village nurseries for six months, and then we would plant them. But almost two years into it, Dr. Vincent Deblauwe, who runs the project on the ground in Cameroon, told us he feared that 25 percent weren’t mature enough, and if we planted them, the survival rate wouldn’t be great. He seemed really concerned because CBI had told us, the funder, that they would be planted after six months. And when I heard this, I was like, “Well, duh. Hold them back, let them grow another year and then plant them. If they’re going to die, don’t plant them.” It felt like our flexibility was alien to them.

Virginia: It’s completely true. That mentality has allowed the project to grow and evolve in ways that it couldn’t without adaptive management, which is built on our relationship and the honesty and the willingness to say “Hey, this isn’t working, let’s try something else.”

Now we are working with funders who say “you told us there would be this many plants in the ground by this date,” and the reason we can meet those objectives is because Bob [Taylor] and Taylor Guitars were willing to accept the up-front cost of figuring out how to do it.

Q: Can you talk about the process of working with local communities? How do you build trust with those communities?

Virginia: Our team will go visit the community, introduce the concept of the project, and leave some information about it. They’ll return about a month later and discuss it again with the community, and if there’s a critical mass of people there who want to participate, we’ll go over a memorandum of understanding (MOU). In order to have a valid contract, both sides have to contribute something, so both the project and the communities co-invest. We’ll leave again and let the community review the MOU and think about whether they want to sign it. We’ll return a third time, and if the community is game to go forward, we’ll schedule a signing ceremony with food, and the project gets started in earnest.

Once the community has decided that they want to participate, they’ll set aside land for the nursery, they’ll nominate nursery managers, and then individuals are welcome, but not obligated to participate, because everything is planted on individual farms. Participation is totally voluntary, but we’ve found that the program is popular enough that neighboring villages will witness it and often ask if they can participate. Funding is the main limitation to how many communities we can work with.

Scott: We had a reporter who went to four or five villages to interview the people who were planting, and asked the same question to each of them: It will be 100 years before these ebony trees are ready, so why are you doing this, apart from getting some monetary payment for the first few years? And a major response point from each person was that it helps with traditional land tenure issues; it helps clarify who owns what. We’re dealing with areas where land tenure can be confusing, and it can get political, but if someone is actively working the land, whether it’s agriculture or reforestation, everyone in the community understands. Everyone notices, everyone sees it, so the project has been helpful with establishing this informal understanding and it conceivably deescalates future tensions between communities.

Virginia: Fast forward a generation or two, and how do you prove that your parent or grandparent planted the tree? In the beginning, Dr. Zak had the idea to create silvacultural booklets for every farmer who participated, with the GPS location of all the trees that they planted. We even got a Cameroonian ministry to stamp [the booklets], but we had no idea if it would be respected in the future. A new forestry law passed this summer actually recognizes the silvacultural booklets as a way to move towards land tenure recognition, which is an exciting step forward.

Q: What made ArcGIS StoryMaps an ideal medium for putting together your report on the Ebony Project?

Scott: We got connected with Esri because a few folks at Esri were frankly Taylor Guitars fans and were intrigued by some of the stuff we were doing with the Ebony Project. They suggested that we use ArcGIS StoryMaps to tell the story of the Ebony Project, and graciously offered guidance and help, as we needed it. Virginia and I were already responsible for putting together the Ebony Project annual reports, which we felt were a little dry and static, like a million pages in size seven font. How many people were we reaching with those? So we thought hey, let’s give this a whack. Let’s see if we can reach a non-traditional audience, a broader audience through a “comic book” version of our annual report as opposed to another text-based annual report.

Virginia: I came up with four acts pretty quickly, and became attached to the idea of these four “epochs,” as I call them: The historical context, the genesis of the project, the present, and then the future. And then Scott was obliging enough to make that work within the stories he wanted to tell.

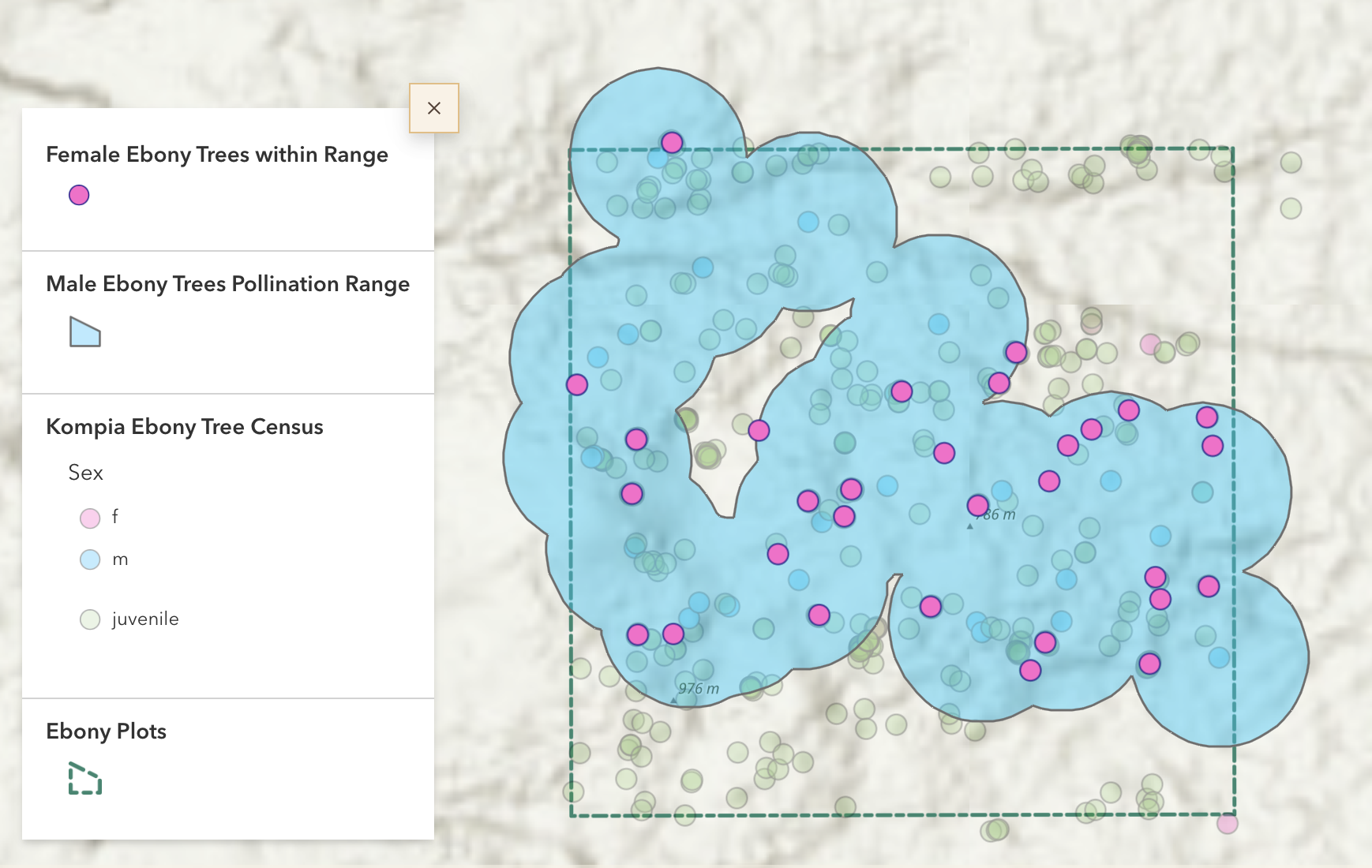

Scott: There was so much that we both wanted to express, we could have easily had eight chapters, or twenty. Virginia was attracted to the science and wanted to explain our research distinguishing male and female trees and the pollination distances between them, and I wanted to explain why Taylor was doing any of this in the first place. Why is ebony important to a luthier, and the rapidly changing global dynamic of sourcing wood to build guitars? But in the back-and-forth creative tension that comes naturally to [Virginia and I], we were able to distill it down to the key storytelling elements that we need to convey.

Q: Looking forward, how can the lessons you’ve taken from working on the Ebony Project report be applied in the future or on a larger scale?

Virginia: Tropical rainforest conservation is both exceptionally important and hard to do well. There are a lot of factors fighting against conserving rainforests, factors that all of us participate in, factors that local populations participate in, and global forces that are causing wide scale destruction. To me, what can be scaled up here is the idea of being really honest about what’s possible [in environmental conservation] and what works for local people. I think ArcGIS StoryMaps has been a really good medium to explore that complexity.

Scott: When we were working on the [ArcGIS StoryMaps collection], we kept asking ourselves, “Who’s the audience?” And as we wrestled over that, we realized that, frankly, the primary audience was the international funding community. The Ebony Project is succeeding beyond our wildest dreams. We’re in 13 villages, and with time and careful growth, we could double, we could triple, we could quadruple. But Bob [Taylor] can’t pay for this forever. Virginia and I know that the international funding community has coalesced around a general framework of deliverables, the multitude of aspects that they want to see projects address. The Ebony Project ticks a lot of boxes and we wanted to show that. Honestly, that’s why the [collection’s] conclusion says “hey, we check a lot of boxes.” It’s because we need to attract more funds to sustain and grow this project.

This featured storyteller interview was prepared as a part of the January 2025 Issue of StoryScape℠ | Reporting for storytelling duty.

For more interviews and articles like this one, be sure to check out StoryScape℠, a monthly digital magazine for ArcGIS StoryMaps that explores the world of place-based storytelling — with a new theme every issue.

Article Discussion: