Susan Straight, a novelist based in Riverside, California, maintains a “fence library” along her front sidewalk. People are free to donate and borrow books, making for an ever-evolving inventory of volumes. The donated books are sometimes brand new; some are recent fiction and nonfiction and some are classic children’s books and novels from decades ago. Most tend to fly quickly off the sidewalk shelves.

Susan happens to live about three blocks from Christian Harder, an editor at Esri Press.

About five years ago, Susan, who was aware that Christian worked for a mapping company, asked him for a blank map of the United States. When he asked her why she needed a blank map, she showed him a collection of paper scraps, Post-it notes, and notepad lists documenting the locations of hundreds of American works of fiction — all compiled in strictly analog form.

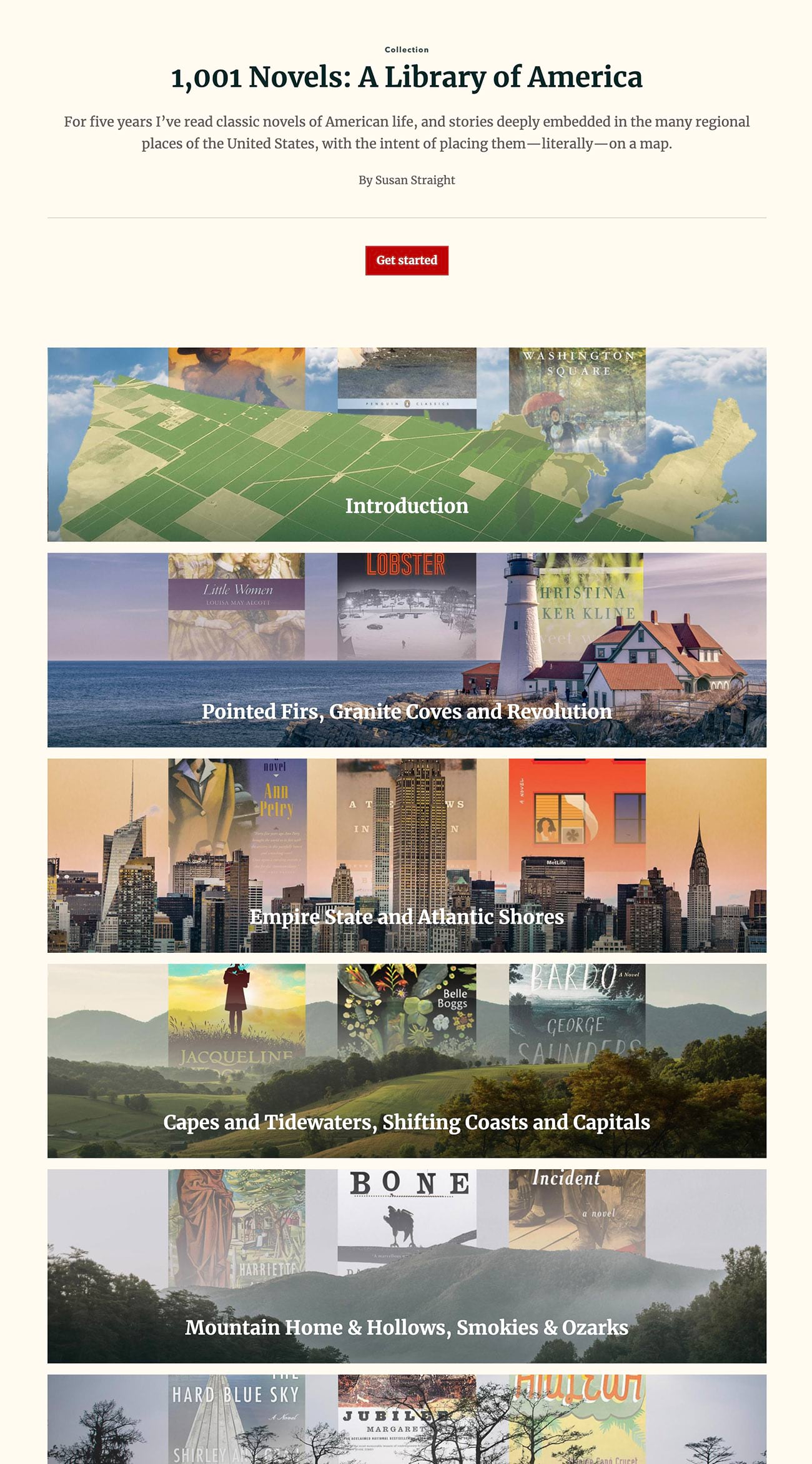

As Susan recollects, Christian asked her why she was collecting locations of works of fiction. She replied, “I don’t know, just seems like a good thing to do.” Christian’s immediate response was to suggest that the project could be done digitally, as an ArcGIS StoryMaps production. Soon thereafter, Christian introduced Susan to me, and thus was born a multi-year effort that is now published as a StoryMaps collection called “1,001 Novels: A Library of America.”

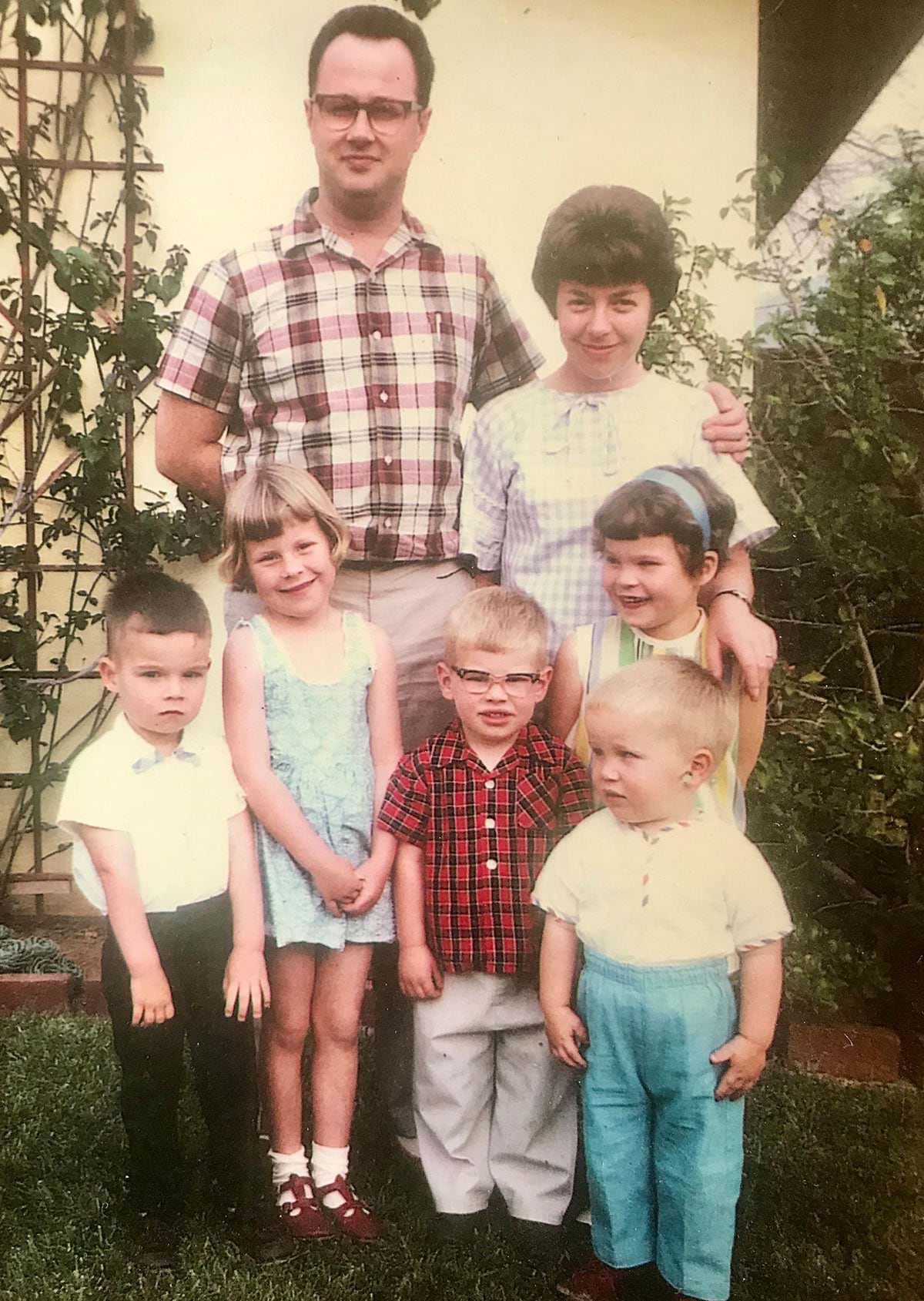

Born and raised in California’s Inland Empire, Susan is a successful novelist (and professor at UC Riverside) whose most recent opus, Mecca, is on the Washington Post’s list of the Ten Best Books of 2022. She grew up with an unusual dual obsession: books and geography. She credits her mother, an immigrant from Switzerland, for her love of books. “She took me to the Riverside Public Library and I read so much and I read so constantly and I was so obsessed with books that by the time I was five, there were three books that shaped me and made me want to do this map and become a writer.” The three: Little Women, Anne of Green Gables, and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Why? In part because all of them were about geography, vividly depicting locales that were dramatically different from Susan’s semi-arid, Southern California surroundings. “My stepfather was from Maritime Canada,” Susan says, “So he gave me Anne of Green Gables, and that book is huge because Anne also wants to be a writer.”

Susan’s stepfather also took her on road trips, a camper in tow. “My dad owned three laundromats, so we cleaned the laundromats on the weekends. He and my mom had five kids. There’s my two siblings and me, and then we had two foster kids. We’d go camping in a little trailer. We always had auto club maps and a road atlas. I was always obsessed with maps. I was the one that he would ask to read the maps because no one else cared. So I loved getting out the road atlas…we went to the Grand Canyon, we went to Yellowstone, we went to Yosemite.”

The result of these childhood influences? “The combination of literature and the road atlas just became ingrained in my mind,” Susan says.

There may not have been a single “Aha!” moment when Susan’s passions were forged into an actual project. But, Susan says, “I think it was after the election in 2016, when everybody was talking about red states and blue states and saying that we have nothing in common. And I just kept thinking it’s so strange to be reading all this beautiful fiction and thinking that we were not two Americas.”

Eventually, Susan’s dual preoccupations — books and geography — came together as a single obsession: populating a map of the U.S. with book titles.

Once Christian had put Susan together with my team, we settled on a structure and approach: Susan would write an introductory, autobiographical essay; she’d dissect the country into a handful of regions suggested by landscape, history, and culture as expressed in novels; she’d introduce each regional section with a brief essay; and team member Lee Bock and I would turn her lists into a series of map tours, one for each region.

Building the stories

Given that this was an ongoing project that involved multiple installments of information, the key requirement for managing the content was flexibility. Susan delivered the book titles, descriptions, and metadata as a series of Word docs. Lee then transferred the information to a spreadsheet, which offers crucial tools for tracking changes.

With the spreadsheet established as the definitive data source, some further automated steps brought the data into a form usable by the ArcGIS StoryMaps system:

- Each novel was assigned to its literary region, as defined by Susan;

- The order of the books in each U.S. state was optimized by proximity to other books, so that the reader’s browsing path through the bookscape would be as smooth as possible; and

- A final process (repeated as necessary) loaded the spreadsheet data and accompanying book cover art into an ArcGIS feature layer with attachments.

The project went through several fits and starts. Its original title was “737 Novels: A Library of America.” Then it evolved into “909 Novels…” somewhat arbitrarily based on the Inland Empire’s area code. A final burst of creative energy upped the count to 1,001, a number with rich literary overtones.

Susan frequently consulted with her novelist compatriots to refine location information. On some occasions she would parse text to determine what real locations might have inspired authors’ descriptions of fictional settings. One of her ground rules was to feature only one book per author, to the chagrin of a few who hoped that several of their novels could find places on the map.

But…why?

So, what, I asked Susan, would she like people to learn or gain from this project?

She didn’t immediately have an answer. Clearly, the exercise in itself was a personal challenge, a joyful pastime. But then she added, “There is very little in the world like reading an actual physical book [and] learning about someplace new through your imagination. But in this particular time of America right now, just to think about reading somebody like, you know, Flannery O’Connor, and then reading somebody who’s writing about Georgia now in a different way, like Tayari Jones.”

“Everything is contained in that. You’re learning history, geography. You’re learning empathy. You’re learning about your fellow Americans or you’re learning about someone who is an immigrant. I think, as a child of an immigrant, my mom found this wonder in America. My mom gave me that joy. It was as if America was a new country for me, too.”

“So…maybe…a little bit less cynicism about this place. And maybe a little bit more about the beauty of this country. It is absolutely astonishing.”

Article Discussion: