There are almost always going to be people who know a lot more than you do about the story you’re trying to tell. By sharing their experience, sources can help fill subject knowledge gaps.

From experts, a storyteller can gain knowledge about an era, events, cultures, places, and trends. It’s not just the legwork they have done as part of their training or education, but also their unique perspective they’ve gained through experience.

When subject matter experts bring their accumulated history to a story they can help you see a subject the way they see it—the way they’ve been involved with it. That guidance and context can make for a more exciting, more enriched story experience. When combined with one’s own research and data collection, expert interviews can also help provide a more accurate, relevant, and reliable story.

This blog post is intended to help you identify and engage with subject matter experts successfully. We’ll start by looking at a few stories that the StoryMaps team has produced where key sources were instrumental.

An expert source can help figure out what threads to pull/aspects to focus on

Picking apart the school lunch is a story about a subject that people think of as complex.

What the experts did here was help identify the key bits and help uncomplicate a range of subtopics. School nutrition directors and policy experts from groups like the School Nutrition Association and Full Plates Full Potentialhelped navigate the U.S. Government’s acronym soup and help pull out the subtle details that make it a compelling story. They provided unique perspective, vital information, and another layer of credibility.

Sources helped the storytellers cultivate other reliable sources and provided introductions. Further credibility was built up through this process.

These sources were also instrumental in helping decipher the mountain of data surrounding school lunches.

They can lend their own credibility to make the story stronger

In the story Opportunity on Two Wheels, members of the StoryMaps and ArcGIS Living Atlas teams set out to examine how the presence of bike infrastructure (or lack thereof) in Washington, D.C., makes it possible for residents of different parts of the city to access everyday needs and amenities. They did so through innovative geospatial analysis—but all the data in the world is only meaningful if you can also provide insight into the why of both the approach and the results.

Fortunately, two representatives of the local bicycle advocacy group in D.C. lent their expertise to the project. Their input helped the storytellers pinpoint the important things to consider in their data analysis, while also providing enlightening insight into the output of the analysis, revealing and explaining some of the more surprising outcomes. In doing so, they lent an additional level of credibility and accuracy to the story and helped the writers avoid assumptions and generalizations.

They can provide personal context

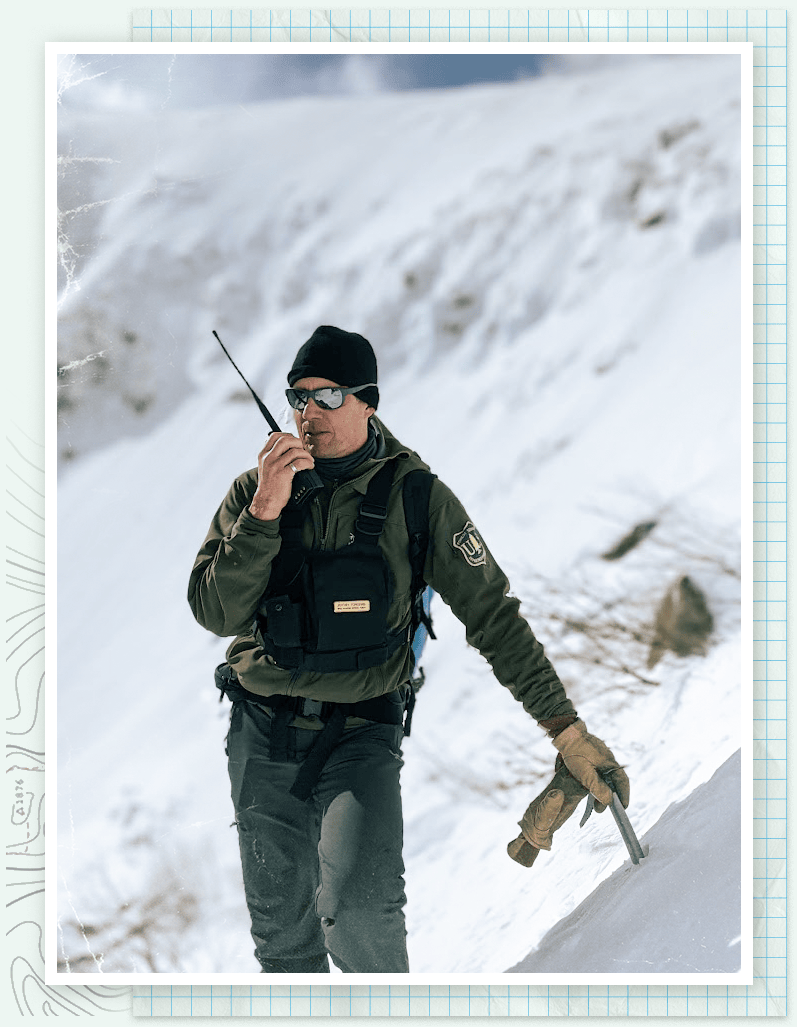

For Answering the call, a story about wilderness search and rescue, talking with people like Jeff Fongemie, acting director of the Mt. Washington Avalanche Center, and Rick Wilcox, former director of Mountain Rescue Service, was essential. These individuals have led, coordinated, and participated in hundreds of rescues over an extended period of time. Their unique perspective makes the story more intimate with their situational knowledge.They understand the critical thinking involved in wilderness searches and rescues and were able to convey that thought process in powerful and engaging quotes.

Jeff and Rick were able to provide situational context based on how they approach their work, which automatically makes the story more inviting. Based on participating in hundreds of search and rescue operations, Rick knows first-hand what it’s like to be on the call around the clock in all kinds of weather. He knows what he and other search and rescue team members are up against when he says:

“We understand time is our enemy. The longer it takes to get to someone, the more chance there is they’re not going to make it,” – Rick Wilcox.

Jeff and Rick are accomplished mountaineers with an intimate knowledge of the White Mountain National Forest in New Hampshire where the story is set. Their awareness of the terrain and weather helped contextualize the landscape as they see it, as people who interact with it every day do.

“To the rescue teams, it doesn’t necessarily feel any more risky than what they do in their daily job as guides,” – Jeff Fongemie.

These quotes, packed with key background context, helped breathe life into an exacting and challenging story.

Finding the right expert sources

The first step is doing research to get at least a baseline handle on the subject you are telling a story about. From there you can begin identifying what sub-topics consistently come up and what questions you may have that are not being answered. With more information gathering you can begin to determine what roles subject matter experts will serve in the telling of this story.

Do you need someone with encyclopedic knowledge to help provide background? What about someone who is personally connected to add experiental knowledge and an emotional touchstone. Maybe you need someone like a statistician who you can call on to help explain why the data you are finding works the way it does.

Often it’s most effective to talk to more than one individual with exceptional knowledge of the subject. This can be especially true when you want to create more depth and perspective, or perhaps offer differing viewpoints.

Interviewing tips

Communicating with interviewees: When scheduling the interview be clear about how much time you will need. If you’re going to be recording the interview let the interviewee know in advance and make sure they are comfortable with it – and-specify whether the recording will entail both audio and video.

Logistics and preparation: Choose your location wisely—do you need to book a quiet room or is sitting outdoors at a picnic table okay?

Do your homework and familiarize yourself with the general subject matter and the person to be interviewed—as relevant to the story. This research should help you figure out and arrange questions and ultimately develop some trust—you’ve shown you are invested.

Construct 10 to 20 meaningful but open-ended questions that encourage the person you are interviewing to talk freely. However, do not ask more than half of them. The interview should be more of a conversation.

When arranging questions, prioritize them according to the goal of the story. Build up to tougher and more personal questions. Be willing to deviate from the list depending on how the interview is going.

Embrace the silences. As difficult as this may be for the interviewer, it is important to let the conversation breathe. Sometimes the person being interviewed needs time to think through what they are going to say or fully recall an experience.

The ideas discussed in this post are intended to provide a solid foundation for understanding and working with expert sources. We hope you will try some of the strategies in your stories. We can’t wait to see what you create.

Cover photo by alesmunt via Adobe Stock, © 2023 (all rights reserved).

Article Discussion: