You have data, but that’s not enough to make a map. You also need a purpose. There’s no point in making a map unless you have something to say.

Making a map means making many decisions. Making decisions without guidance is hard. Making decisions toward a goal is easier. Consider these common questions:

- What should I title this map?

- Which color scheme should I use?

- Should I include this layer on the map?

- Do I need a legend?

- Should I include a chart in the pop-ups?

- What should be the extent of this map?

- What medium should I use to share this map?

Until you’ve decided on your map’s purpose, answering these questions will remain difficult.

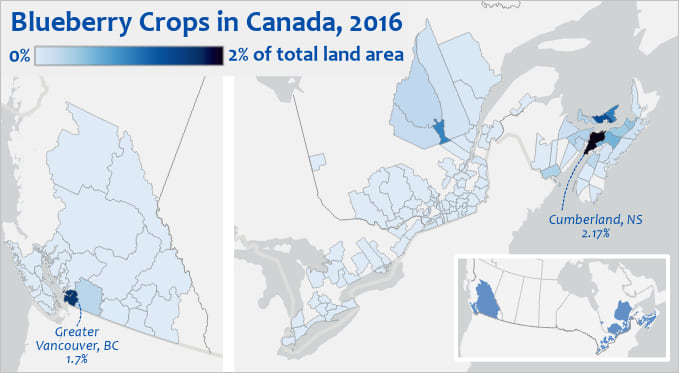

I made the map above without knowing what I wanted to say. My lack of intent resulted in an uninteresting map.

That’s ok! Experimenting with symbology, making charts, and exploring the attribute table are all important methods that you should use to become familiar with your data. Never assume that you already know what your data says, or what you want to say with it. Making different maps is one method for arriving at your intention.

But it’s important to distinguish between the maps you make for yourself—to help you explore your data—and the maps you make to share with others. The maps you make to share should be purposeful.

If I stopped my experimentation here and called the map complete, what messages would be communicated to the reader?

- Blueberries are not grown in the middle of Canada.

- Cumberland County, Nova Scotia, grows a lot of blueberries considering its size.

Your map will always convey some message. It’s important to assess if it’s the message you intended.

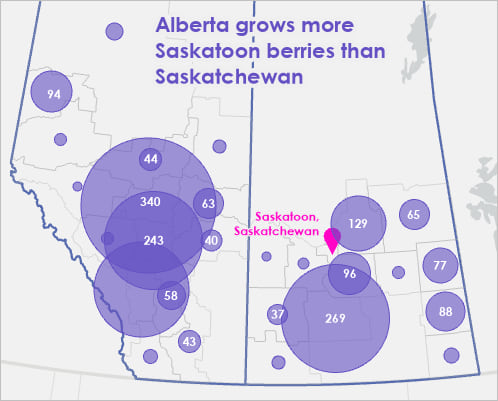

You can communicate your intended message more clearly if you design the map with it in mind. If the messages listed above were intentional, rather than accidental, I might arrive at this map:

I made the map above knowing what I wanted to say. This goal led to the following decisions:

- I added text to emphasize Cumberland County and to compare it to its closest rival, Greater Vancouver.

- To make it easier to compare the relative colors, I zoomed in on the blueberry-growing regions and cut out the empty middle of the map.

- Removing the middle of the map also helped to emphasize the lack of blueberry crops in Central Canada.

- The map is a bit disorienting with its middle missing. To compensate, I added a locator map. This also emphasizes the empty center.

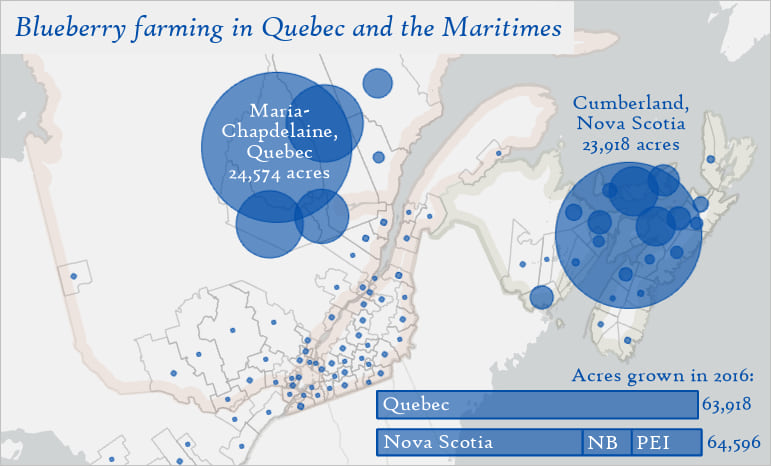

Consider a different map intention: to determine which region grows more blueberries, Quebec or the Maritime provinces.

This intention is narrower and more focused. It results in a more effective and interesting map.

With the exceptions of basemap and projection, every decision I made for this map differs from the previous two maps because I was guided by a different goal.

- Quebec is large, so showing blueberry crops as a percentage of total land area didn’t do it justice. Switching to proportional symbols allowed me to show Quebec as a major player in the blueberry industry.

- In 2016, Quebec and the Maritimes were almost perfectly tied for dominance in blueberry farming. I added a chart to illustrate this.

- British Columbia and Ontario also grow blueberries, but they are not relevant to this map’s goal, so I didn’t show them.

- The title is about the intent of the map, not the contents of the data.

- I outlined the regions that are being compared. The colors are faint, so they don’t compete with the primary data.

- I chose a font that softens the tone of the map, to avoid the appearance of competition between the two regions.

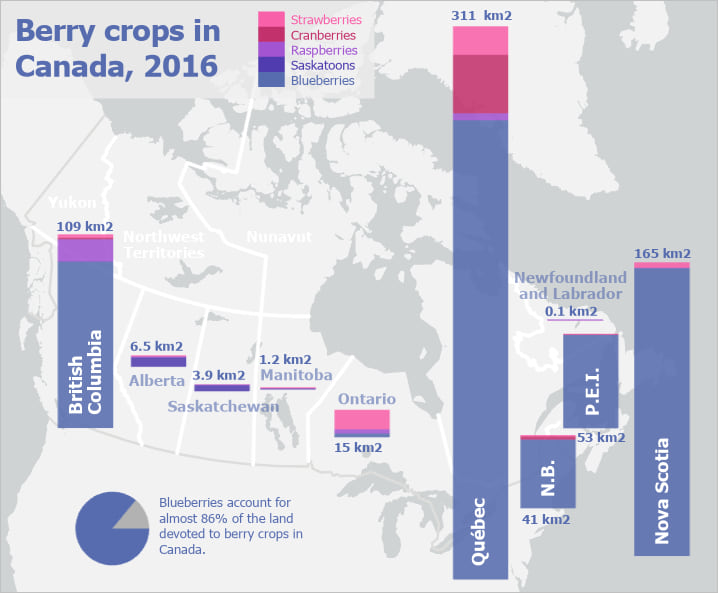

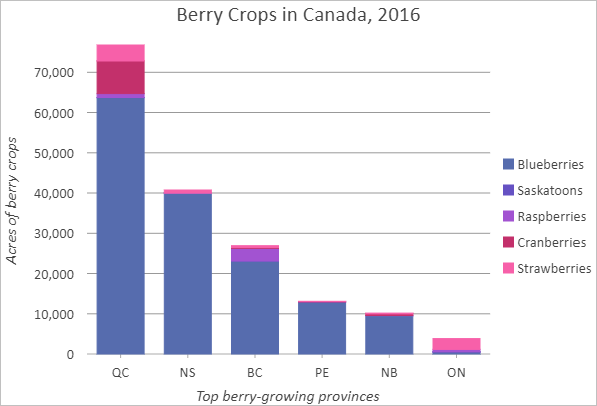

Consider one more intention: to show that blueberries are the dominant berry crop grown in Canada.

For this map, comparing blueberries to other berry crops was important. Symbolizing by charts allowed me to do that.

Should you even make a map? If you find that you’re fighting with your map to make it say what you want it to say, consider other methods of presenting your data. In the example above, do I need to show the geography? Could a single stacked bar chart convey my message more clearly?

In all of these examples, shifting the intention resulted in different choices and different maps. What is the intention of your map? Why are you making it? What do you want it to say?

You can phrase it as a goal:

- Help campers find their campsite and the nearest bathroom.

- Convince councilors that a new commercial development in your town will be beneficial.

- Educate children about the history of colonialism.

You can phrase it as a statement:

- Our company offers better shipping services than our competitors.

- This is a remote region with great natural beauty and few services.

- This lake has been shrinking since 1965.

You can phrase it as a question:

- Where are sensitive ecosystems most at risk in this country?

- Where should you locate a new health clinic?

- Which intersections have the most traffic accidents?

Make sure that your map doesn’t just ask the question—it should also answer it.

Gone are the days when maps merely stored information. We have computers for that now. A good map has something to say.

You can download MappingWithPurpose.ppkx to view all of the maps shown in this article and see how they were constructed in ArcGIS Pro. The primary dataset used in these maps is the Census of Agriculture 2016 – Crops layer from ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World, sourced from the Government of Canada 2016 Census of Agriculture.

You can find more cartography tutorials on the Introduction to Cartography page.

Article Discussion: