When you are trying to choose a coordinate system for your map, are you sometimes confused by the options?

What is the difference between a geographic coordinate system (GCS) and a projected coordinate system (PCS) anyways?

Here’s the short answer:

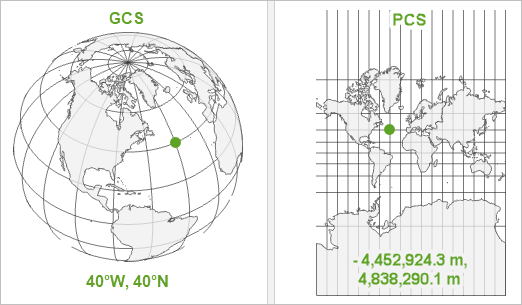

- A GCS defines where the data is located on the earth’s surface.

- A PCS tells the data how to draw on a flat surface, like on a paper map or a computer screen.

- A GCS is round, and so records locations in angular units (usually degrees). A PCS is flat, so it records locations in linear units (usually meters).

Where: Geographic Coordinate Systems

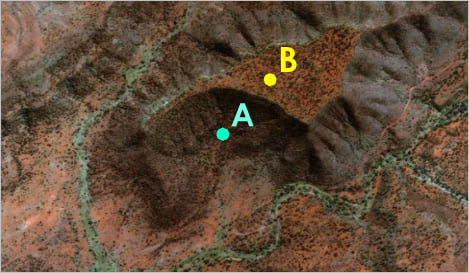

You are part of a search and rescue team looking for an injured person in the Australian outback. The point location you have from her satellite phone is 134.577°E, 24.006°S. Where is she located?

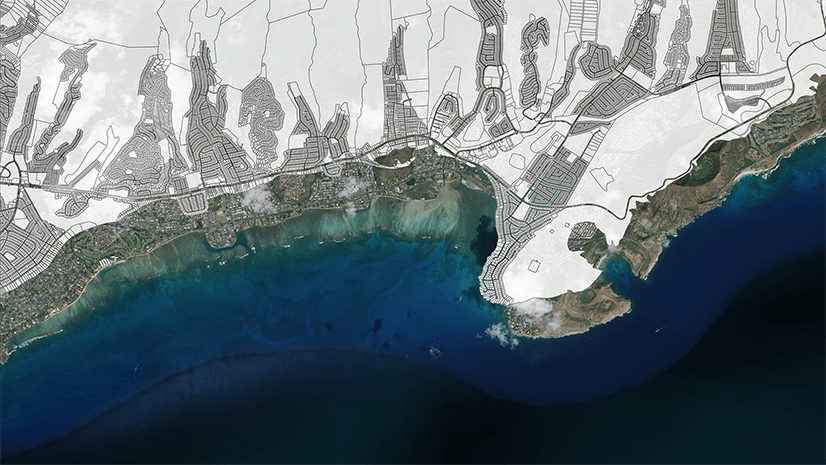

Both location A and B in the above image are correct. A is 134.577°E, 24.006°S in one GCS (Australian Geodetic Datum 1984) and B is the same coordinate location in another (WGS 1984). Without knowing which GCS the data is in, you don’t know if the hiker is on top of the plateau or if she has fallen off the cliff.

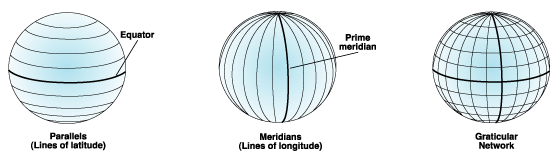

A geographic coordinate system (GCS) is used to define locations on a model of the surface of the earth. The GCS uses a network of imaginary lines (longitude and latitude) to define locations. This network is called a graticule.

So why isn’t knowing the latitude and longitude of a location good enough to know where it is? How can location A and location B in the Australia example both be correct?

Well it turns out the earth isn’t a perfect sphere. It’s a lumpy, bumpy, and uneven rounded surface. There are high mountains and deep ocean trenches. Because the planet spins, the poles are a bit closer to the center of the earth than the equator is. But in order to draw a graticule, you need a model of the earth that is at least a regular spheroid, if not a perfect sphere.

There are many different models of the earth’s surface, and therefore many different GCS! World Geodetic System 1984 (WGS 1984) is designed as a one-size-fits-all GCS, good for mapping global data. Australian Geodetic Datum 1984 is designed to fit the earth snugly around Australia, giving you good precision for this continent but poor accuracy anywhere else.

The GCS is what ties your coordinate values to real locations on the earth. The coordinates 134.577°E, 24.006°S only tell you where a location is within a geographic coordinate system. You still need to know which GCS it is in before you know where it is on Earth.

How: Projected Coordinate Systems

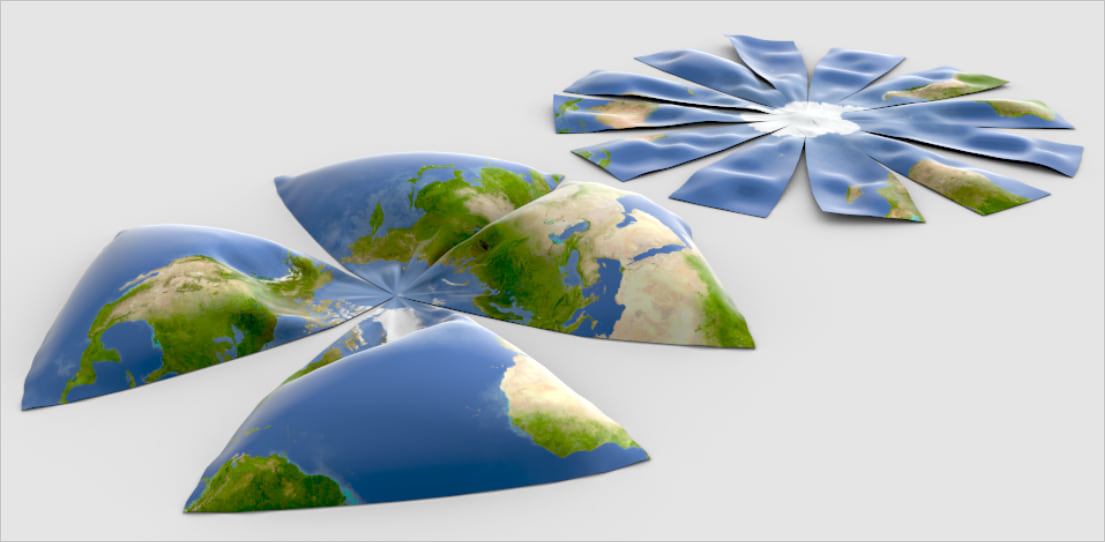

Once your data knows where to draw, it needs to know how. The earth’s surface—and your GCS—are round, but your map—and your computer screen—are flat. That’s a problem. You can’t draw the round earth on a flat surface without deforming it. Imagine peeling an orange and trying to lay the peel flat on a table. You can get close, but only if you start tearing the peel apart. This is where map projections come in. They tell you how to distort the earth—how to tear and stretch that orange peel—so the parts that are most important to your map get the least distorted and are displayed best on the flat surface of the map.

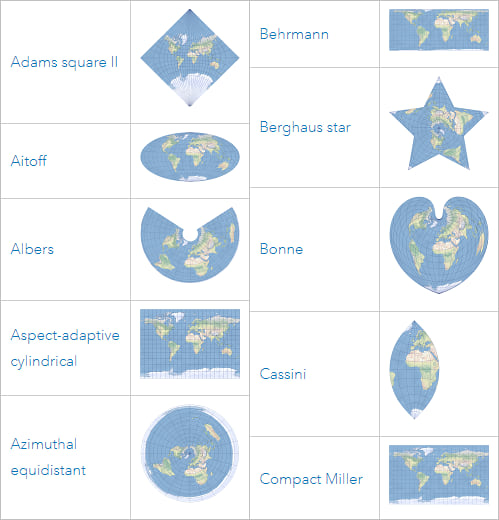

You’re perhaps already aware that there are many different map projections and that each displays the earth in a different way. Some are good for preserving areas on your map, others at preserving angles or distances.

A projected coordinate system (PCS) is a GCS that has been flattened using a map projection.

Your data must have a GCS before it knows where it is on earth. Projecting your data is optional, but projecting your map is not. Maps are flat, so your map must have a PCS in order to know how to draw.

Next, let’s take a look at how these coordinate systems (geographic and projected alike) are put together.

Coordinate System Construction

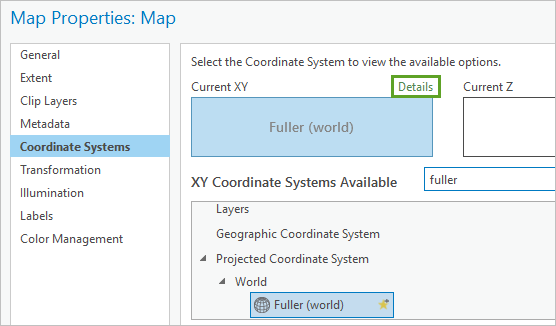

In ArcGIS Pro, you can view the details of any coordinate system in the Map Properties window, on the Coordinate Systems tab. Click the green Details link.

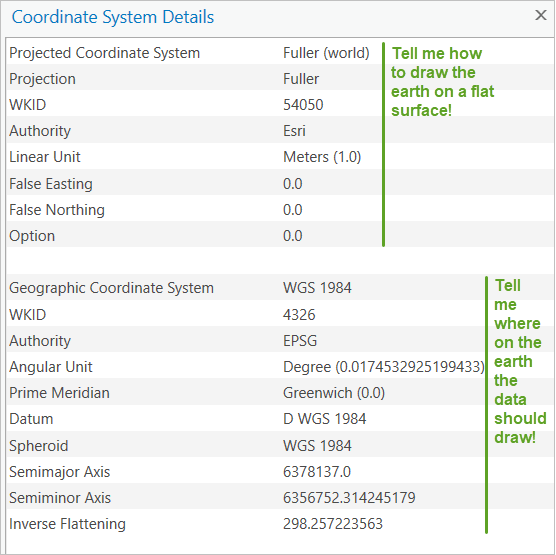

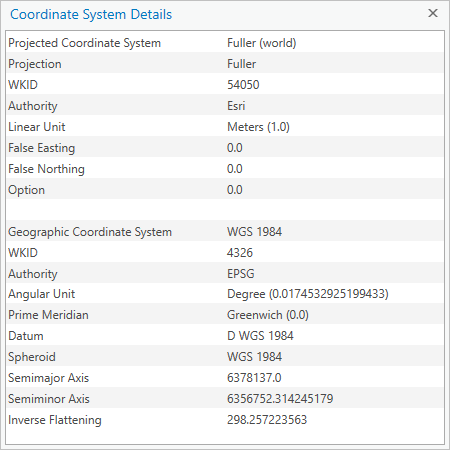

The image below shows the Details page for the Fuller (world) coordinate system:

- The first line tells you that it’s a Projected Coordinate System, as opposed to a GCS.

- A PCS, by definition, uses a Projection. The second line tells you that this PCS uses the Fuller projection, which was invented by Buckminster Fuller in 1954.

- WKID is a unique identifier number for the PCS, defined by its Authority.

- Coordinates in a PCS are recorded in a Linear Unit, often meters.

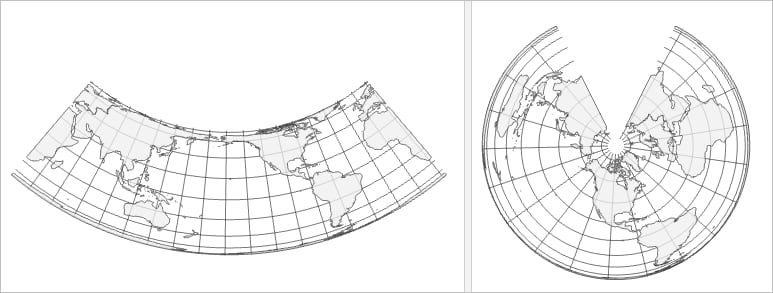

- False Easting, False Northing, and Option are parameters specific to the Fuller projection. Other projections have parameters like Central Meridian, Standard Parallel, and Latitude of Origin. You can often modify these parameters to center the PCS on a specific location. Below are two different PCS: Hawaii Albers Equal Area Conic and Canada Albers Equal Area Conic. They both use the same projection but different projection parameters.

- A PCS also contains a Geographic Coordinate System! In this case, it’s WGS 1984.

Remember that a PCS is just a GCS that has been projected. Let’s look at the properties of the WGS 1984 geographic coordinate system:

- It has a WKID (and Authority) as well.

- Coordinates in a GCS are recorded in an Angular Unit, usually degrees.

- The Prime Meridian is an arbitrary line of longitude that is defined as 0°. It typically runs through Greenwich, England, but it doesn’t have to.

- The Datum defines which model is used to represent the earth’s surface and where that model is positioned relative to the surface.

- The Spheroid is the regular model of the irregular earth. It’s part of the datum. Semimajor Axis, Semiminor Axis, and Inverse Flattening define the size of the spheroid.

But wait!

Can’t we choose a GCS for our map instead of a PCS? I’ve made maps before that were in WGS 1984 and they drew just fine, didn’t they?

Let’s try it out.

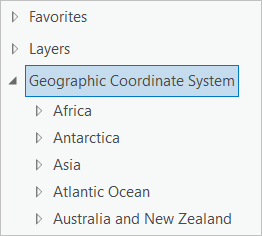

In Map Properties, expand the Geographic Coordinate System list and choose any one. Click OK.

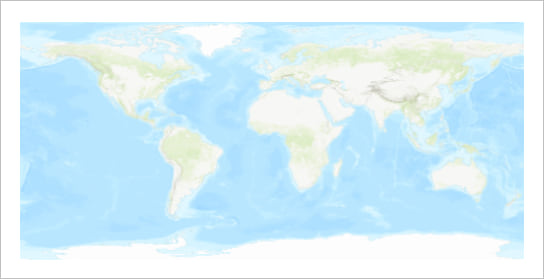

Your map will look like this, regardless of which GCS you chose:

Remember that it is impossible to draw the round earth on a flat surface without a projection. So when you tell ArcGIS to make a flat map with a GCS, it is forced to choose a projection! So it draws using a pseudo Plate Carrée projection. This is just latitude and longitude represented as a simple grid of squares. It is called pseudo because it is measured in angular units (degrees) rather than linear units (meters). This projection is easy to understand and easy to compute, but it also distorts all areas, angles, and distances, so it is senseless to use it for analysis and measurement. You should choose a different PCS.

Summary:

- You can store your data in a GCS. But you can’t draw it on a flat map without a PCS.

- The GCS tells your data where to draw. The PCS tells the map how to stretch the GCS out flat.

- Which GCS you choose depends on where you are mapping.

- Which PCS you use depends on where you are mapping, but also the nature of your map—for example, should you distort area to preserve angles, or vice versa?

Most of the time, you don’t need to choose a GCS. Your data was already stored in one and you should just stick with that. But often you do need to choose a PCS. Read the lesson Choose the Right Projection to learn how to pick the right one.

There are plenty of other resources that help to explain coordinate systems in greater depth and in different ways. If you want to learn more, try some of these:

- Coordinate systems, projections, and transformations

- Basics of Map Projections

- Map Projections in ArcGIS

You can also read these other articles that I have written about coordinate systems:

- Coordinate Systems: What’s the Difference?

- Projection on the fly and geographic transformations

- Define Projection or Project?

- Transformation warning: What does it mean and what should I do?

Cloth globe image by Charles Preppernau.

Many thanks Heather Smith. The concept of pseudo Plate Carrée projection is now clear to me.

The where vs. how framework you constructed here is useful for distinguishing geographic coordinates from their projected counterparts. Thank you for sharing it so effectively. I take issue, however, with the paragraph that defines geographic coordinate systems and graticules as equivalent (i.e., as a grid of lines). A GCS definitely is NOT a grid of lines. I’m disappointed to see this misconception presented as fact in an Esri sponsored blog because it takes so long to get students to relinquish it. A GCS is a continuous and 3-dimensional {lon, lat, AND either radius, height, or depth} coordinate system that’s useful… Read more »

Thanks Scott for this clarification!

I have edited the text to reflect your point about referring to a GCS as a grid.

Regarding heights, you are correct. There are many 3D geographic coordinate systems like NAD83(2011) which also record the height or depth of locations, making them three dimensional geographic coordinate systems. This article is restricted to the simpler 2D GCS, defining positions on the earth’s ellipsoidal surface. Prior to the development of GPS, all GCS were only two dimensional, for example NAD27.

Thank you for considering my comment. If I may, I respectfully challenge your assertion that all GCSs prior to GPS were two dimensional, for it is impossible to project distances or areas to scale without knowing the radius (sphere) or the radii (ellipsoid). See John Snyder’s treatise on map projections (every equation). Longitude and latitude are not what makes a GCS geographic; rather, it’s the length(s) of the radius(ii). The Selenographic coor.sys (moon), the Aerographic coor.sys (Mars), and my basketball coor.sys all use {long,lat} pairs to describe where something is on those 3-D objects, but it’s the radius of each… Read more »

Great explanation and examples for the definition of the GCS and PCS. This is by far the best I have read! Thank you.

Great explanation… I take advantage of your PCS knowledge to ask you which kind of projection (must be Equal area) would you use for the Ocean Indian area that EAST to WEST goes from Suez to Philippines and NORTH_SOUTH from coastline to the Equator? Thank you!

Hi Luigi,

I recommend a couple of resources for making this decision: Quick Notes on Map Projections in ArcGIS, and Projection Wizard. I think Cylindrical equal-area would be an appropriate projection for this case. You can create a custom PCS in ArcGIS Pro or ArcMap using the projection parameters suggested by Projection Wizard.

Hi Heather, thank you for the answer. The Projection Wizard suggest me the Cylindrical equal-area projection for regional maps with an east-west extent, Standard parallel: 15º 38′ N, Central meridian: 078º 39′ E for my area of interest. In ArcMap is the World_Cylindrical_Equal_Area, WKID: 54034. Do you think I should modify it acoording to the standard parallel and central meridian calculated?

Hi Luigi,

Yes, I would modify 54034 with the new values if I were you.

I’ve also written a new lesson Choose the Right Projection , which shares some different methods and resources for making this kind of choice, and explains how to modify coordinate systems in ArcGIS Pro.

Thank you for explaining it so well. I understood it finally

I loved this article from start to finish and like some other reviewers here found it to be the best explanation of GPS vs. PCS. Looking forward to some of your other articles.

My university cartography course instructor assigned this piece of reading to us and I found it was incredibly clear (and fun to read!) for both exam review and practical understanding purposes. Thank you so much for this contribution, Heather!

Thank you!! this is one of the most straight forward and simple explanations of the difference between GCS and PCS! appreciate your contribution Heather! keep adding 🙂

Hey Heather,

Can you please tell me which PCS is used in the third figure (comparison between GCS and PCS)?

It is Web Mercator.