About the author: Megan Harris is Senior Reference Specialist for the Veterans History Project (VHP) at the Library of Congress. She helps researchers and the general public access over 110,000 unique collections in the VHP archive, and is passionate about using historical materials to inspire a sense of connection to the past and an appreciation of the infinite stories it contains.

Robert Horr’s flight log is about the size of a steno pad. Beneath its brown, pebbled cover the log is filled with neatly hand-printed lists of locations, dates, and types of aircraft. Flipping through the pages, its contents might not catch your attention. That is, until you get to the last entry, dated June 6, 1944, which proclaims in big block letters, “INVASION STARTED.”

Horr’s flight log, which chronicles his training as a glider pilot in the months leading up to D-Day, is one of hundreds of thousands of items held by the Veterans History Project (VHP) at the Library of Congress. Created by Congressional legislation in 2000, VHP’s mission is to collect, preserve, and make accessible the personal accounts of U.S. veterans who served from WWI through the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. We at VHP invite the general public to contribute the stories of veterans in their lives and communities by donating materials ranging from oral history interviews to personal correspondence, diaries, scrapbooks, photographs, and even artwork.

A familiar story told in a new way

In late 2018, looking ahead to the 75th anniversary of D-Day in June 2019, my colleagues and I searched for an innovative way to interpret our holdings related to the invasion of Normandy. For an archive rooted in individual stories, what better way to explore D-Day than through a story made with Esri Story Maps?

The result is D-Day Journeys: Personal Geographies of D-Day, 75 years later (which, coincidentally, has been named the Story Map of the Month for June). In the initial stages of its creation, we pondered how to present a new perspective on such a well-known and monumental historical event, and how to create a navigable and cohesive narrative out of source material derived from thousands of D-Day accounts in our archive. In the end, we decided to tell the larger story of D-Day by zooming in on four individual stories.

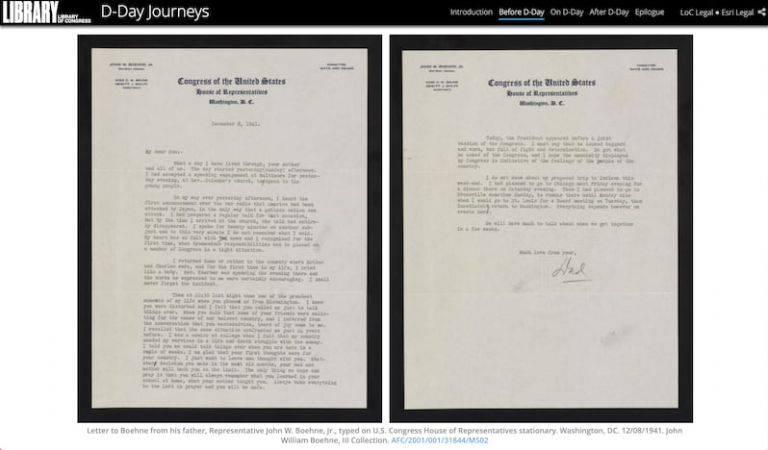

We focused our story map on the wartime journeys of Preston Earl Bagent, a combat engineer; Robert “Bob” Harlan Horr, a glider pilot; Edward Duncan Cameron, a rifleman; and John William “Bill” Boehne, III, a sailor. Instead of simply discussing what they endured on D-Day, we mapped their service experiences from start to finish, from basic training to the end of the war.

This choice was based on the premise that for those who landed in Normandy, World War II was about more than just June 6, 1944. Privileging what happened on a single day—albeit a very important day—over what came before and after excludes important parts of the participants’ narratives. Shifting our attention from D-Day itself to these veterans’ complete experiences let us design a story map that represents more fully what the invasion of Normandy meant to those who took part.

Digging deeper with personal narratives

Limiting our view to four veterans also freed us to do a deep dive into four singular stories, and to explore the full range of primary sources in these veterans’ collections.

Consider the case of Bob Horr’s flight log. I’ve used this object in a number of exhibits, pointing viewers toward its gripping final entry, which narrates Horr’s experiences on D-Day, including the loss of his best friend, Claude R. “Buck” Jackson. But it was not until we incorporated the log into the story map that I realized the full scope of the story it contains. My colleague Samantha (Sam) Meier undertook the painstaking task of mining location data from Horr’s log and the other primary sources we utilized, marshalling the source material into a cohesive narrative, and then formatting our extracted data to create individual maps that show each veteran’s locations before, on, and after D-Day.

Presented this way, alongside original photographs from his collection, Horr’s flight log takes on a new life. Instead of a confusing mix of unfamiliar place names and aeronautic terminology, the log now offers an intimate view into the life of a young glider pilot as he crisscrossed the country on training flights and made side trips to visit the young woman who would become his wife.

Mapping the places that Horr and the other three veterans visited also viscerally conveys the arduousness of their travels. We used a 3D web scene to illustrate the veterans’ travels from the U.S. to their overseas deployment. While at first glance, this seems like just another fun, eye-catching feature, it also demonstrates just how much ground the men covered during the war as they traveled from camp to camp and country to country.

More than just four journeys

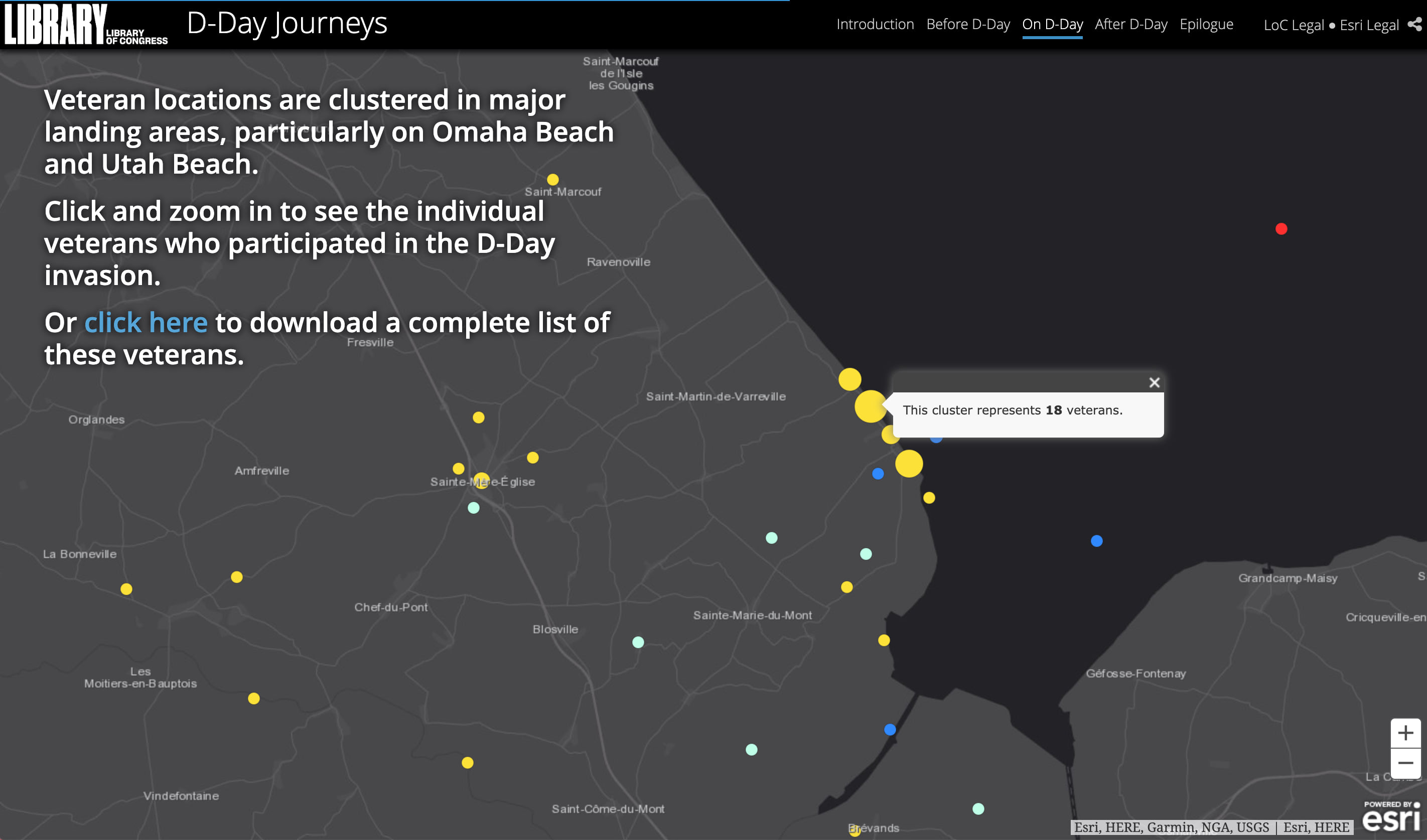

Though we chose to follow the journeys of Bagent, Horr, Cameron and Boehne, we also wanted to illuminate the experiences of other D-Day veterans whose stories are preserved in VHP’s archive. First, we scoured our Normandy collections to determine the veterans’ exact locations on D-Day. Then, we visualized this data in a map, featured in the “On D-Day” section of our story map, which includes data points for over 238 individual veterans. To improve the legibility of this map, we clustered the data points to show broad location trends while still allowing users to narrow in on a particular veteran’s experience.

Ultimately, the process of constructing “D-Day Journeys” took us on our own journey through these four veterans’ narratives and collections, during which we made a number of unexpected discoveries. For example, Sam unearthed the record of a veteran whose name was eerily familiar—Claude R. Jackson. Though Horr had reported Jackson’s death in his flight log, in fact, he had been evacuated to a hospital in England, surviving the invasion. Tragically, Horr was killed in a glider accident a few weeks after D-Day, and never knew his best friend’s true fate. Both Horr’s and Jackson’s collections were donated to the Veterans History Project by Horr’s daughter, who was born four months after Horr’s death.

Discoveries such as these are part of the joy of archival research. The beauty of Esri Story Maps, and the Story Map Cascade template in particular, is that they invite the reader to engage in this process of discovery simply by scrolling through the story. We hope that our story map helps to forge a new understanding of D-Day, of the power of individual stories, and of the importance of preserving oral histories and archival material through the Veterans History Project.

Article Discussion: