Great storytelling rarely happens by accident—it’s the result of thoughtful, intentional choices about content and structure. ArcGIS StoryMaps makes it easy to assemble narrative text, maps, and other multimedia elements into place-based stories. But if those elements aren’t structured in an inviting and logical manner, the story may fail to engage or resonate with its intended audience.

This challenge isn’t unique to place-based storytelling with ArcGIS StoryMaps; after all, even a star-studded cast can’t save a film from a loose, meandering screenplay. Fortunately, we can draw insights from other storytelling disciplines—including journalism, content strategy, and even screenwriting—to shape stronger narratives.

This post explores three common narrative structures—the pyramid, the inverted pyramid, and the kabob—that can serve as useful guardrails when creating place-based stories with ArcGIS StoryMaps. Rooted in millennia of Western storytelling traditions, these structures offer time-tested approaches to organizing content in ways that keep audiences engaged. We’ve gone one step further and refocused these narrative structures on place-based stories—i.e., those that focus on particular geographies or geographic themes, often using maps and spatial context to enrich understanding.

The best structure for your story will depend on your goals, audience, and key messages. This is not an exhaustive list, and you should think of these structures not as rigid rules, but as helpful guides. By arranging your content with intention—and by removing elements that disrupt the narrative rhythm—you’ll create a more compelling experience that resonates from start to finish.

Keep reading to learn more about each of these three structures or use the links below to jump ahead. We’ve included several illustrative examples for each structure, along with a template to jump-start your own story creation.

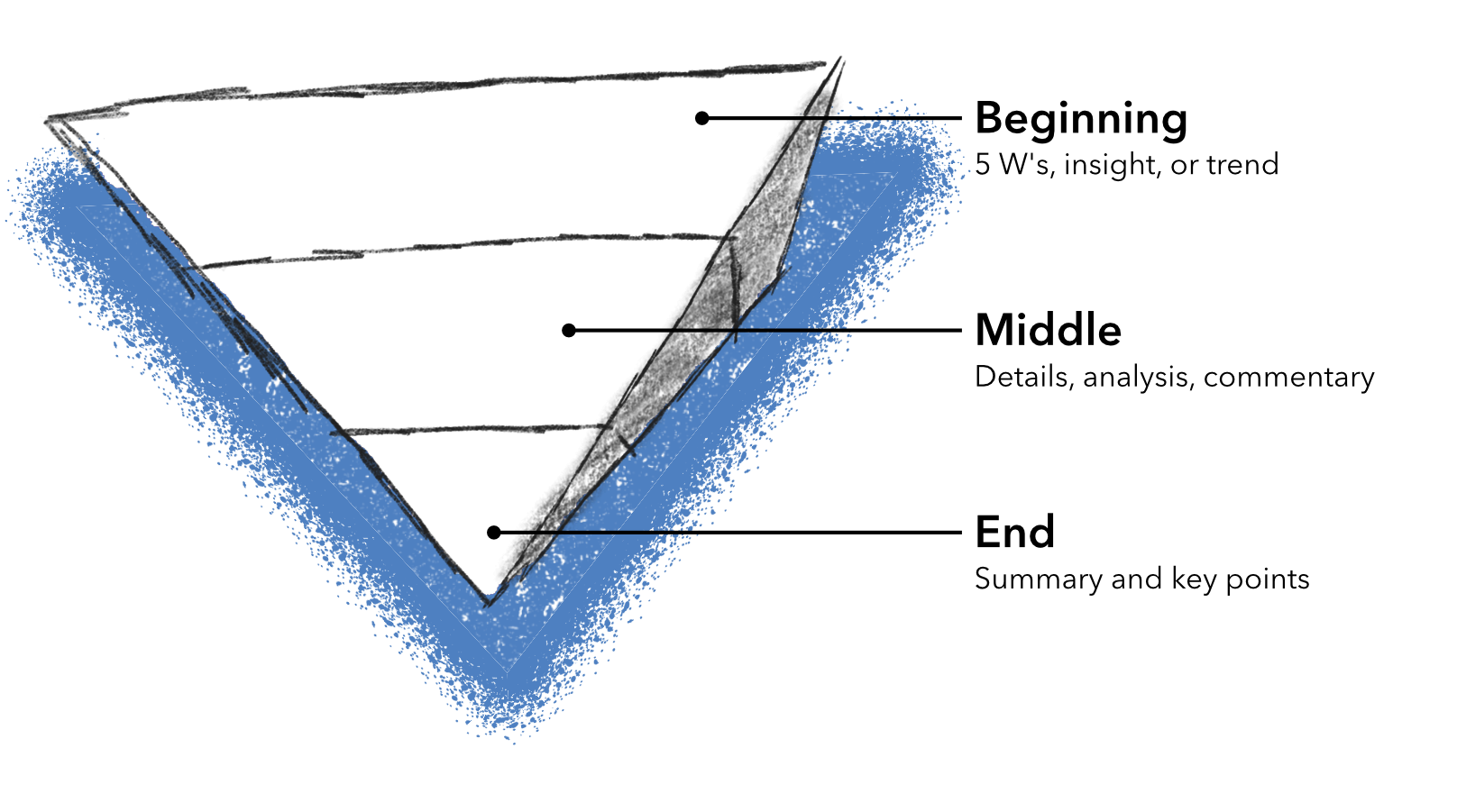

Inverted pyramid

The inverted pyramid is a front-loaded storytelling structure that positions the most important information at the very beginning of the story. This structure prioritizes immediacy, ensuring that readers can grasp the key messages or insights right away. Supporting details and context follow, with the least critical (but still relevant) information placed at the end of the story.

Basic structure

- Beginning: Starts with the most vital information—the “who, what, when, why, and where.” Depending on the focus of the story, this initial insight could be a major geographic trend or insight, or a specific event or record, often illustrated by a thematic map.

- Middle: Provides additional details, such as more geographic data, historical background, or expert analysis or commentary.

- End: Wraps up with supplementary resources or a summary. Often reiterates key points for emphasis but rarely introduces new concepts or ideas.

Common use cases

- Communicating breaking news or urgent insights—for example, mapping like the immediate effects of a natural disaster or public health crisis.

- Engaging audiences with limited time or attention, who may lose patience for longer-form storytelling.

Limitations

- This structure can feel abrupt when applied to nuanced topics or stories that benefit from a more gradual narrative introduction.

- It can also lack emotional engagement, as the introduction often prioritizes facts and takeaways over more evocative storytelling devices like anecdotes or suspense.

Examples

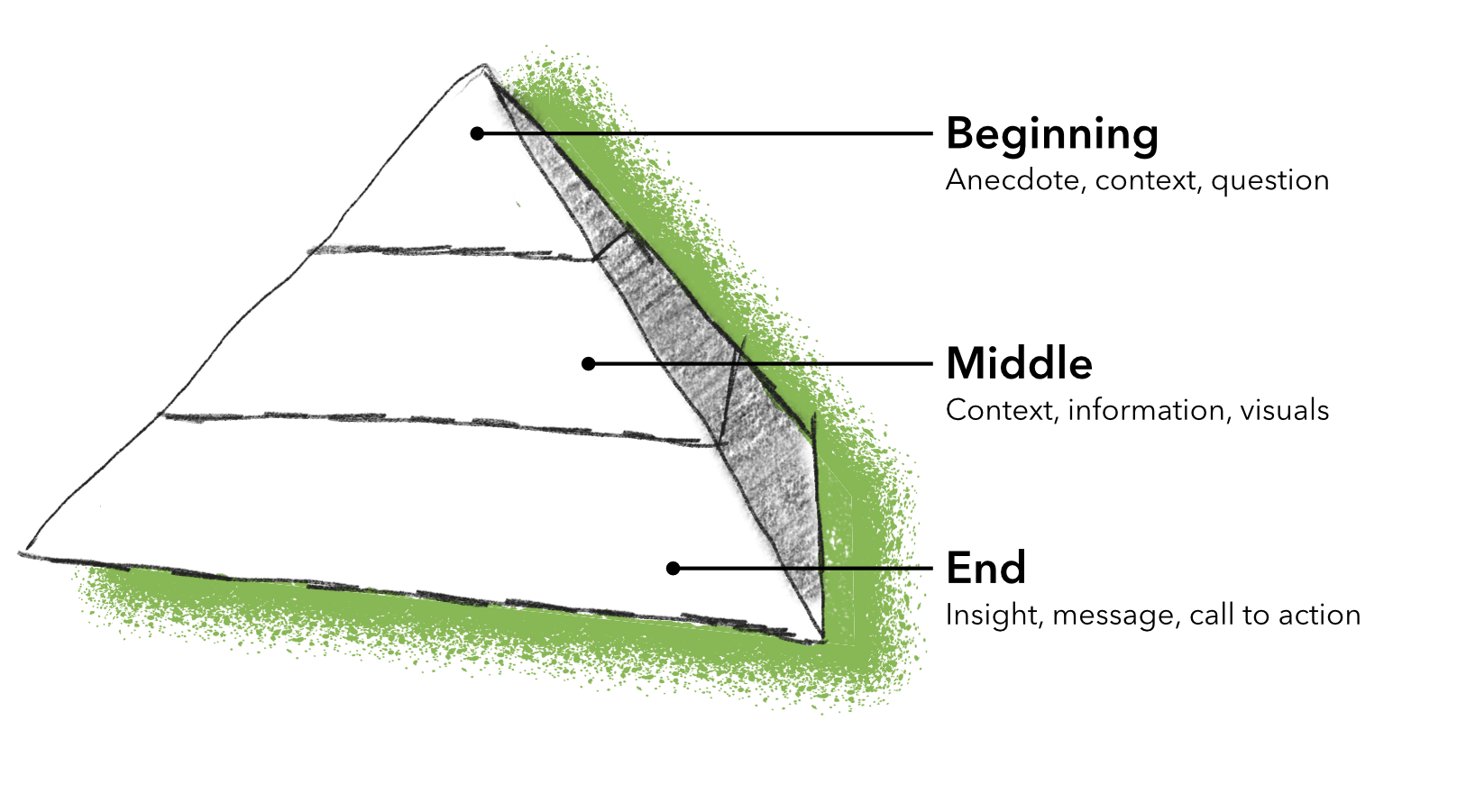

Pyramid

The pyramid (not to be confused with Freytag’s Pyramid, a different narrative model) is a climactic storytelling structure that begins with context and background information (including simple reference maps to help orient readers) before gradually building toward a central insight or conclusion (often communicated through thematic maps). This structure emphasizes suspense and narrative flow over immediate insights, making it a great fit for complex or exploratory stories that require significant up-front context or explanation.

Basic structure

- Beginning: Opens with a compelling anecdote, big-picture context, or thought-provoking question. Uses reference maps to establish the story’s geographic scope. Sets the stage for the story but doesn’t reveal its conclusion.

- Middle: Introduces and weaves in additional layers of context and information, often using thematic maps, charts, or other data visualizations to develop the story.

- End: Delivers the most important insight or call to action (sometimes in the form of an exploratory map), leaving readers with a clear understanding of the story’s key messages.

Common use cases

- Explaining complex geographic insights that require significant up-front context.

- Introducing exploratory data visualizations, such as dashboards.

- Persuading readers to engage with an issue or take action.

Limitations

- If the opening isn’t engaging—or is too long—then readers may leave the story before they reach its key message.

Examples

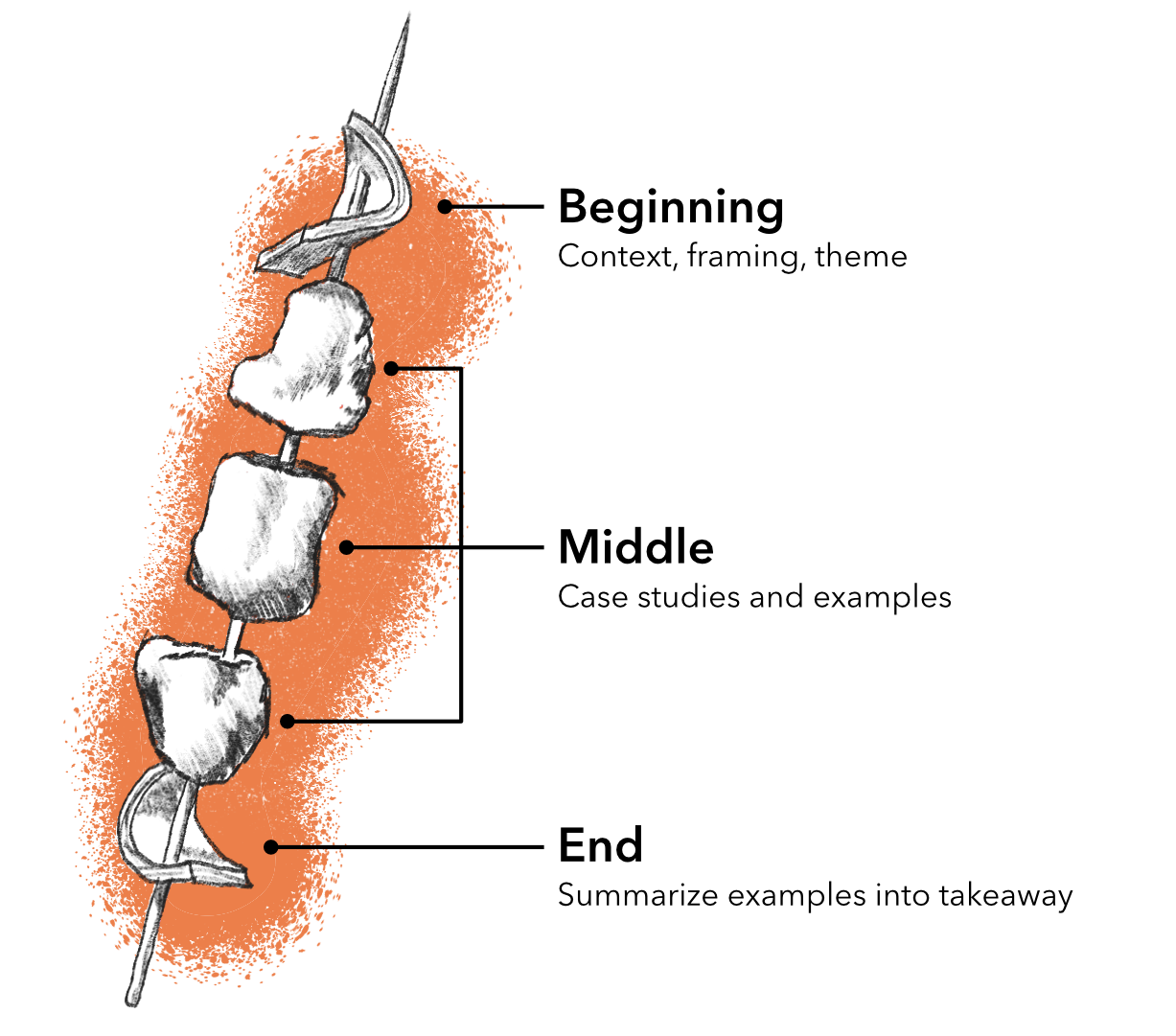

Kabob

The kabob structure is a list-driven storytelling structure where the basic narrative consists of a central theme or message supported by multiple examples or case studies. These examples are typically visualized using thematic maps and are often sequenced together using map choreography. Each example is of equal importance and ties back to the overarching message. This structure is well-suited for data-driven or comparative stories that seek to highlight multiple perspectives.

Basic structure

- Beginning: Begins with high-level context or framing. The key insight may or may not appear right away, but the introduction should establish the overarching theme of the story. If the story focuses on multiple datasets within a single geographic area, a reference map can help orient readers.

- Middle: The “skewer” of examples or case studies. These examples often explore a single dataset across different geographies (e.g., comparing housing affordability across cities) or highlight multiple datasets within a single geography (e.g., comparing various economic indicators within a single city).

- End: Synthesizes the examples into a cohesive takeaway or insight that reinforces the story’s central theme.

Common use cases

- Telling data-rich stories that rely on repeated examples to reinforce patterns or trends.

- Creating geographic listicles or stories where multiple examples hold equal weight.

Limitations

- Can feel repetitive, especially if the examples aren’t varied or engaging enough.

- Can feel reductive, as the structure might oversimplify nuanced stories by focusing heavily on examples.

- Can feel disjointed if the examples aren’t clearly connected to one another.

Examples

Going beyond the basics

The three narrative structures above are suitable for a wide range of place-based storytelling use cases. But these basic building blocks can also be combined in interesting ways to support more nuanced narratives, or to create more immersive experiences for engaged audiences. Below are two additional “compound” story structures. These are especially well-suited for complex narratives that may require a bit more context or exposition than the simpler structures accommodate.

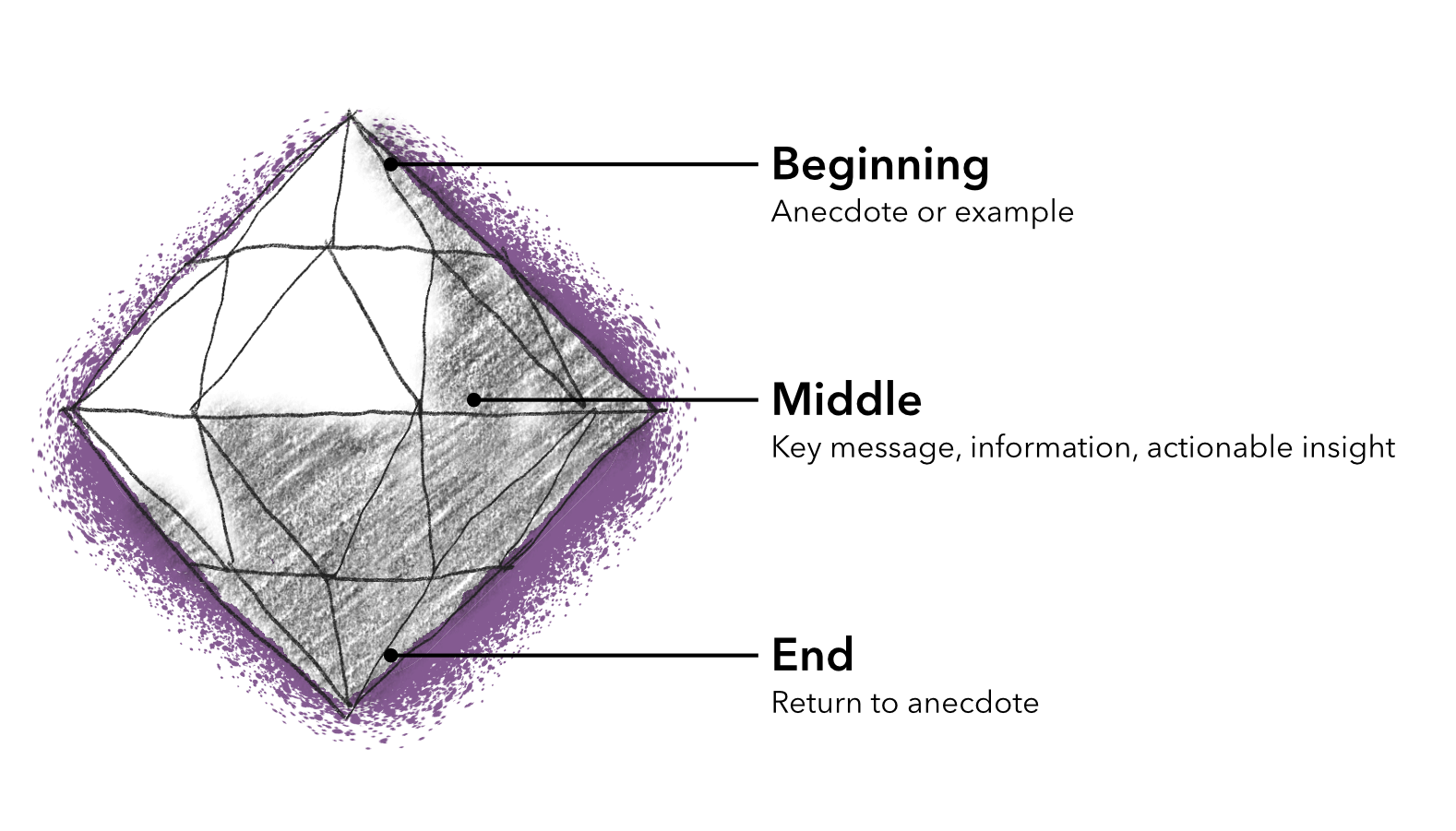

Diamond (pyramid + inverted pyramid)

The diamond structure combines the pyramid and inverted pyramid structures, effectively sandwiching the key message between the introduction and conclusion. The diamond structure is well-suited for complex, data-driven stories whose insights are best communicated through anecdotes or local perspectives.

Basic Structure

- Beginning: Eases readers into the story with a humanizing anecdote or specific example.

- Middle: Introduces the story’s key message or information—often a specific geographic trend or actionable insight.

- End: Returns to initial example, and ties it back to the story’s overarching theme or message.

Common use cases

- Humanizing data-driven stories by leading with anecdotes or examples presented at a human scale.

- Bridging local and global perspectives by alternating between individual examples and big-picture geographic insights

- Highlighting solutions and success stories by beginning with an example, then zooming out to explore how those solutions could be applied elsewhere, before finally returning to the original success story as a hopeful conclusion.

Limitations

- Can easily become overly long, such that readers never reach the story’s conclusion.

Examples

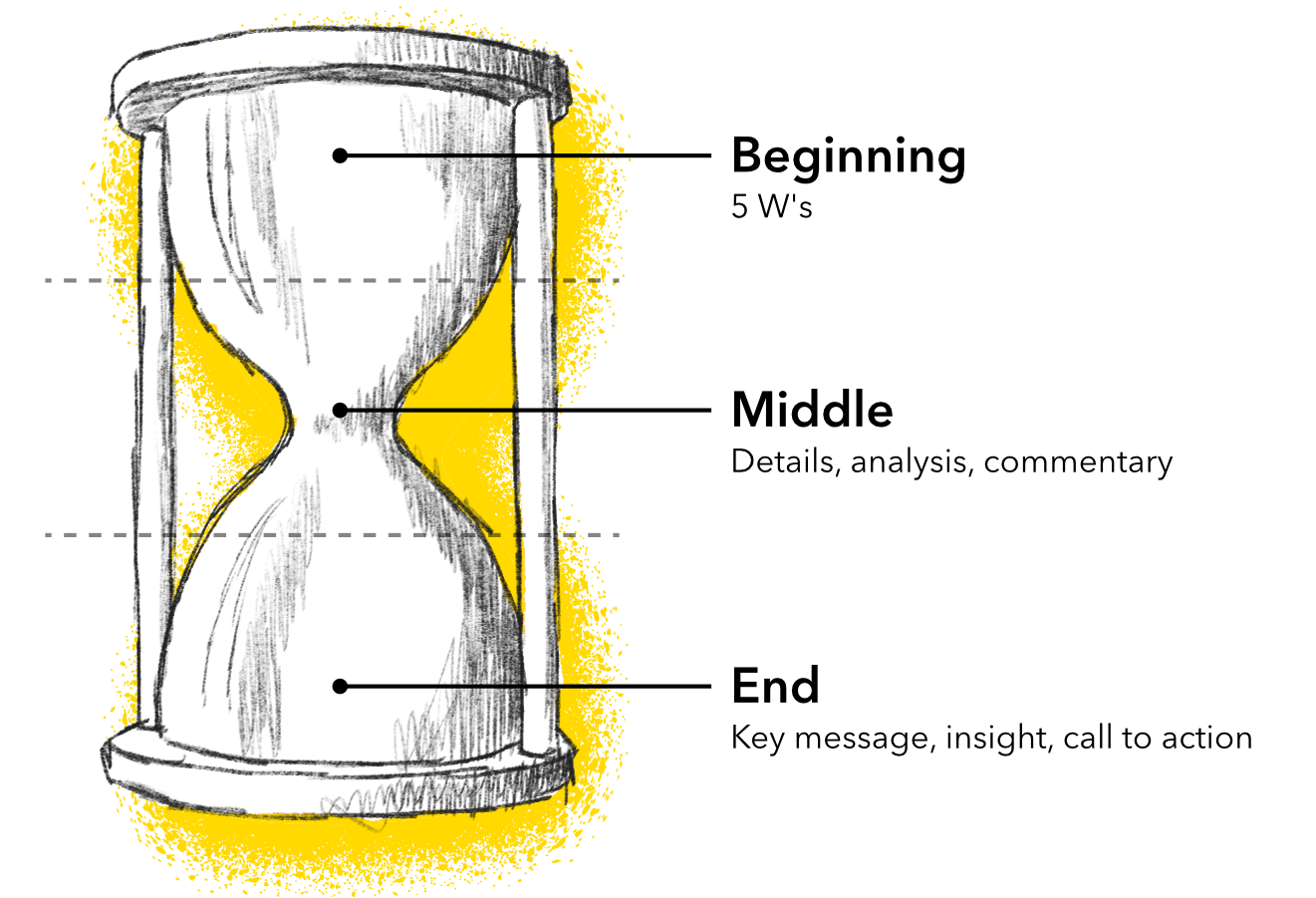

Hourglass (inverted pyramid + pyramid)

The hourglass structure combines the narrative immediacy of the inverted pyramid with the increasing depth of the pyramid structure. In contrast to the diamond structure, the hourglass sandwiches examples or context between the story’s main insights or takeaways.

Basic structure

- Beginning: Starts with the most vital information—the “who, what, when, why, and where.”

- Middle: Provides additional details, such as more geographic data, historical background, or expert analysis or commentary.

- End: Reinforces the story’s key message or insight, and often concludes with a call to action.

Common use cases

- Communicating urgent geographic insights with narrative depth. This structure allows for more nuanced explanation and illustrative narratives than the inverted pyramid alone.

Limitations

- Abrupt transitions between sections—especially from the introduction into the middle section—can undermine narrative cohesion.

Examples

Conclusion

Whether you’re using the pyramid structure to build suspense, or the inverted pyramid structure to draw attention to an urgent issue, or the kabob to weave together multiple perspectives, these frameworks provide a solid foundation for crafting engaging place-based narratives.

Storytelling is also an art, and one that is honed through curiosity and experimentation. So, the next time you go to create a geographic story with ArcGIS StoryMaps, think about how structure can shape your message, guide your audience, and bring your content to life. This process may require some trial and error, and it’s okay to alter or abandon a particular framework once your story has begun to take shape.

Ultimately, the right framework can transform a collection of maps, media, and text into a cohesive, compelling experience—one that informs, inspires, and resonates long after the last scroll.

Article Discussion: