Water is as vital to the cycles of global business as it is to our daily lives. It cools supercomputers that process global transactions, powers hydroelectric energy, replenishes crops that nourish people and livestock, and washes everything from surgical tools to semiconductor chips.

With the oceans covering nearly three-fourths of the earth’s surface, too many business executives and individuals pay little attention to water management. But an alarming drumbeat of rising temperatures, worsening droughts, and depleted aquifers is puncturing that complacency, with profound consequences for companies and the economic and social order.

In late 2021, S&P Global named water scarcity the biggest threat to corporate assets in the coming decades—greater than hurricanes, wildfires, and other hazards. By 2030, water demand is expected to exceed supply by 40 percent worldwide, and half the human population will live in water-stressed areas, according to a McKinsey analysis.

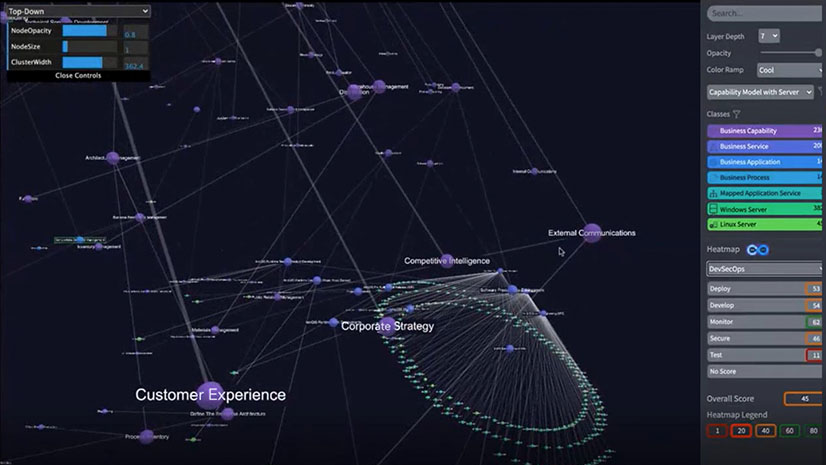

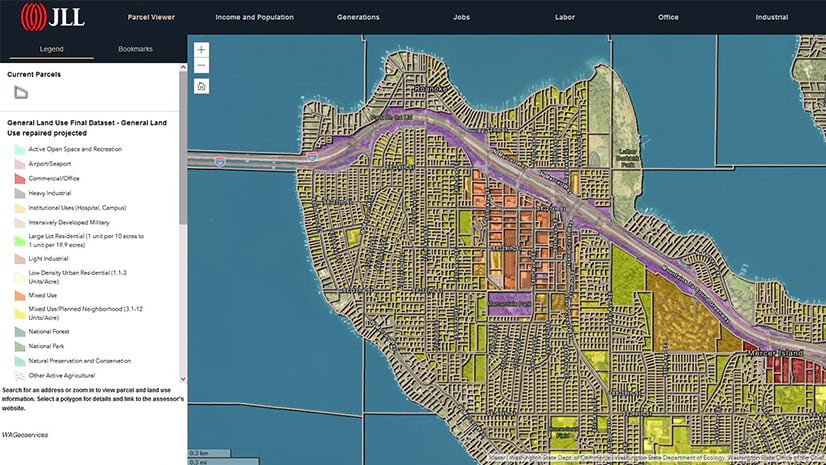

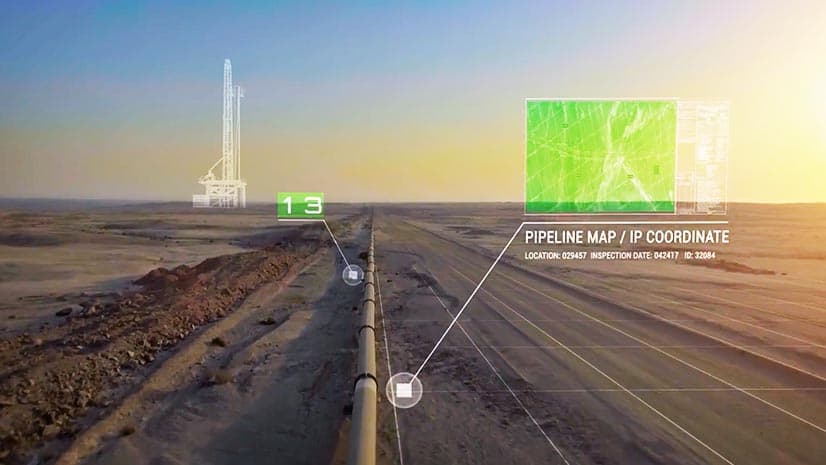

A geographic approach shows promise for guiding companies through this challenge. To understand the risk of water stress to their networks and suppliers, forward-thinking business leaders are turning to a geographic information system (GIS) to capture and analyze relevant data in a location-based context.

Water Management: A Sustainability Priority Executives Can’t Ignore

Because water is critical to the daily operations of countless industries, smart management of this resource has already become the number one sustainability priority for a select group of firms.

With a GIS-based smart map of a company’s international operations, a supply chain or manufacturing executive can layer visualizations of data about global warming rates, flood risks, storm overflows, water quality, drainage, groundwater status, or drought intensity—all key components of water management.

Insights from GIS, known as location intelligence, are generating a new understanding of the true price and productivity of water. A company’s utility bill might be cheap—but the cost of building a textile factory in a region where water scarcity could paralyze operations in a few years is not.

The operational intelligence GIS provides (see sidebar for more on how GIS works) can help organizations discover sources of waste as well as ways to reuse water that will cut costs and benefit local communities. Location technology empowers business leaders to analyze water-related risks and opportunities, respecting the limits of natural resources as well as an organization’s bottom line.

Without such visibility, executives run the risk of making costly decisions when planning the locations of production or capital investments.

A Flood of Change

In some regions, water-related disruptions aren’t a looming danger but an immediate threat, with real impacts on global commerce. When the worst drought in a half-century hit Taiwan in 2021, it temporarily crippled the country’s semiconductor industry, compounding the auto industry’s supply woes and underscoring the need for water management. In a typical day, a chip-producing facility uses up to 4 million gallons of ultrapure water (filtered to become particle-free) to clean components. In Taiwan, producers were forced to ration water; the world’s largest contract chipmaker even began buying water by the truckload.

Supply chains were similarly rattled when a 2018 heat wave lowered the water levels of Germany’s Rhine river, one of the country’s major shipping routes. Freighters reduced cargo or stopped transportation altogether, halting production and driving up manufacturing costs.

Poor water management poses reputational risks as well. In places like India and Mexico, companies have scrapped plans for new facilities when local communities, worried about equitable access to watersheds, raised outcries.

Major tech companies—many of which operate water-intensive data centers—are among the most prominent corporate voices calling for a new relationship with water. Microsoft, Facebook, and Google have all pledged to become “water positive” by 2030—meaning they will replenish more water than they use.

But in nearly every sector, there are signs of a dawning awareness that the water-use calculations of the past no longer hold. Companies as diverse as the clothing manufacturer Lululemon, the beer producer Molson Coors, and ride-sharing service Lyft have all begun including water risk assessments in their annual SEC reports.

For most businesses, the trajectory points toward a changing relationship with water, says Charles Fishman, a journalist and the author of The Big Thirst: The Secret Life and Turbulent Future of Water. “Whatever your water status quo is, it’s going to be disrupted,” he told WhereNext.

Water, Water, Everywhere . . .

Forward-looking companies are aiming to get out ahead of the issue and adjust decision-making now to forestall water-related disruptions. By interlacing data on ecological and economic trends, GIS helps identify potential impacts to an organization and its stakeholders. With that data, C-suite leaders can rank the locations of greatest priority, determine the next course of action, and monitor impacts using dashboards or smart maps.

“It is really important to ask, ‘What impact does water have on our operation—beyond cost?’” Fishman says. Water tends to be cheap, so price isn’t a reliable indicator of its value. Instead, a simple way to gauge its impact is to determine what would happen if the water were turned off. “Most places would be in a world of hurt in 14 different ways,” he says.

Before businesses can improve water management, they first must be able to measure the amount of water they’re using. A strong grasp of geographic context is almost always necessary to answer that question comprehensively. To fully know where water comes from, and where it goes once a business has used it, leaders must be able to view the entire chain of operations—from global headquarters to tier 3 suppliers—not just the assets the company owns.

The bulk of water use often occurs outside the company’s direct line of sight. In the case of a clothing retailer, for instance, McKinsey found that subsuppliers account for as much as 90 percent of water use through the supply chain. The retailer’s own operations might add just 1 percent.

Fishman says the critical questions are simple and direct:

- How much water do we use at each step?

- What do we use that water for?

- Where does the water come from, and where does it go once we’ve used it?

Most companies don’t know the answers to even those basic questions, according to Fishman. That lack of transparency on how and where water flows through the supply chain can leave a firm open to serious risk. For example, the savings that a food manufacturer achieves from reducing water use in its factories could be dwarfed by overuse of water among its business partners. As the Taiwanese drought shows, the loss of water at any stage of production can imperil the whole supply chain. Mapping the use of resources throughout the supply network raises awareness—and the effectiveness of any water management plan.

Managing What You Measure

One of America’s leading consumer goods corporations is taking a geographic approach to assessing water risk throughout its supply chain. The company’s manufacturing operations, which process millions of cubic meters of water a year, require access to clean water.

With GIS, the company’s leaders see maps showing the hundreds of suppliers and factories around the world that contribute to its products, complete with detailed information on local water and climate risk. That level of location intelligence enables manufacturing executives to flag water-stressed areas and identify scenarios to mitigate risk, including relocating facilities. The maps also serve as important tools to communicate findings to stakeholders, including the public.

Measuring and mapping water usage can provide insights that end up streamlining entire workflows. Ford Motor Company’s initiative to improve water management, which reduced water use by 10 billion gallons between 2000 and 2015, began with a simple request from then-CEO Bill Ford. According to Fishman’s reporting, the chief executive asked each Ford facility to begin reporting monthly water use. The discovery that 10 percent of water was lost through leaks in fire-protection systems triggered a push for efficiencies throughout the production process. Ultimately, the automaker worked with its paint suppliers to create a new color coating, which helped cut the amount of water required per car to 1,000 gallons from 2,200. Years later, Fishman reported, a severe drought hit northern Mexico. Had Ford not optimized its water use, three factories in the region would have shut down; thanks to the efficiencies, they remained open and functioning, without competing for water resources with their surrounding communities during a drought.

Cooperative use is also a useful strategy when businesses have no choice but to maintain operations in a water-stressed area. Executives can join with nearby firms—potentially even competitors—to lessen demand on local water infrastructure by alternating patterns of use or recycling water. Location intelligence can facilitate this kind of win-win by identifying potential cooperative-use partners in a market.

Location: The Key to Water Risk and Water Management

Once an organization understands the geographic context of water use, the next task is to analyze how the resource is employed. Many businesses chill, heat, steam, dispose of, or filter water to fit their needs—processes that all tack on cost.

Sensors and indoor location intelligence can help facilities managers track water use inside buildings and factories. Just as GIS enables building managers to monitor energy use in offices or the security of IT assets, it can identify patterns of water excess or opportunities for recycling.

No matter what human beings do, they cannot create or destroy water. But the resource can disappear from areas where it supports industry and communities, leaving scarcity or even desertification in its wake. It can begin appearing in places where it hasn’t been, in the form of floods or rising sea levels, causing damage and disruption. In other words, whether and how water poses a risk depends largely on location. In the decisive years ahead, GIS will be an indispensable tool to help businesses and communities understand these dynamics, act as responsible stewards, and make the most of every drop.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |