Americans spend $1.1 trillion on food every year, but new research suggests the actual cost is much higher.

Production and distribution practices in the US food industry create what economists call external costs, and when researchers at the Rockefeller Foundation analyzed the true cost of food in the US, they arrived at a figure of more than $3 trillion. These costs to the environment and public health are hidden, but very real, and they’re borne by consumers and producers alike.

Before business leaders can design a sustainable food system and a more resilient business model, they must understand how, why, and where current practices contribute to these shared expenses. Location intelligence, as part of a data-driven strategy aimed at addressing inefficiencies, is a valuable place to start.

Food Costs Accumulate in Unexpected Places

According to the Rockefeller Foundation, health-care costs alone, including money spent treating diseases linked to diet, double the cost of food. For the most part, these costs are a consequence of consumer choices and persistent inequities in access to healthy food options.

Two other metrics—environment and biodiversity—together impose nearly as much external cost as ill health does. The foundation measured environmental costs in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and soil erosion, arriving at a tab of $350 billion. The damage to biodiversity—from land use; runoff; and pollution of soil, air, and water—adds another $455 billion.

These costs, directly related to agricultural and industrial practices, add nearly 75 cents’ worth of damage to the earth for every dollar consumers spend on food. It’s clear from the implications of the report that companies can take steps to limit these costs—and that location intelligence from modern geographic information systems (GIS) technology can bring insight to decision-making and actions.

Reduction and Resilience

In recent years, forward-thinking companies involved in food production and distribution have harnessed location data to uncover efficiencies for their businesses—efficiencies that boost the bottom line even as they benefit the planet.

The solution to the problem they’re addressing has two major components—reduction and resilience. Companies must adopt practices that reduce negative impacts on the natural world, including minimizing greenhouse gas emissions, habitat destruction, and biodiversity threats. They must also build resilience by assessing and mitigating climate-related risks that increase their costs or threaten the business’s future.

In short, companies can reduce the negative costs of food production by protecting the planet and themselves, and a geographic approach using location technology can support this effort by helping to make sense of relevant data.

The Importance of Feedback Loops

To understand how closely the goals of reduction and resilience are aligned, consider the feedback loop, an important concept in climate change scenarios. In one common example, when sea ice melts, oceans lose their power to reflect sunlight and end up absorbing more heat from the sun. That, in turn, causes more sea ice to melt.

The relationship between food production and biodiversity displays a comparable pattern. Agricultural practices are major contributors to biodiversity loss, and this destruction threatens companies’ ability to practice agriculture.

The practice of resilience follows a similar logic. Companies can use location intelligence to predict climate threats to fields or production facilities. They might find that a crop grows better in a certain geographic region or a certain section of a field. Those adjustments help ensure the business’s future revenue, but if they are not accompanied by production changes that lessen the company’s carbon footprint, they’ll further the climate crisis and adverse growing conditions.

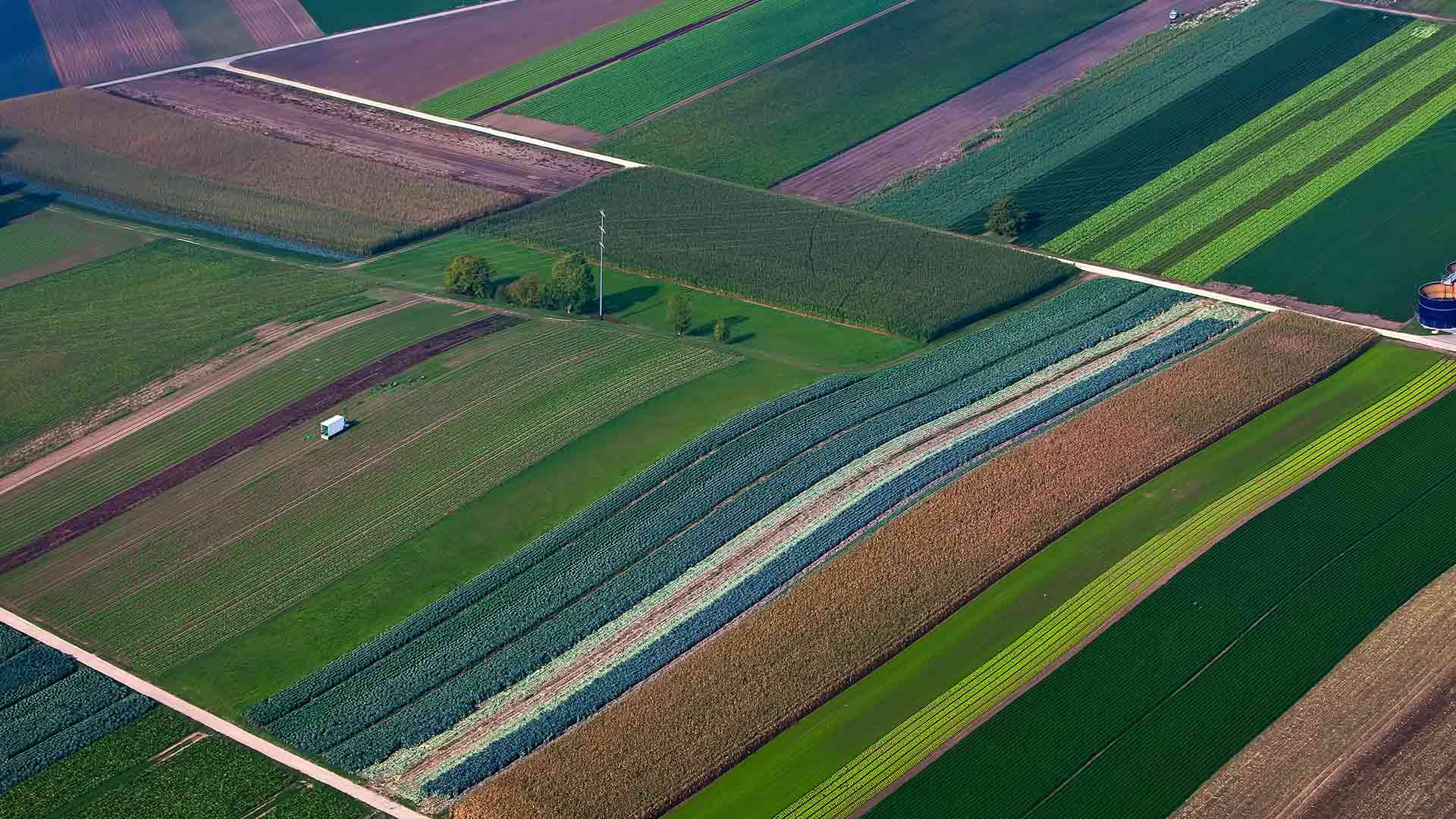

The reduction steps companies must take to protect the planet are therefore impossible to separate from the resilience actions they must take to protect profits. Taking action to protect planet and profit means first analyzing how a company operates. Because most of that analysis is rooted in location-specific data—everything from understanding patterns of irrigation and runoff, to siting farms based on changing climate conditions, to examining how soil conditions affect seed choice—GIS is the analytical framework many companies depend on.

Making Connections to Reduce the Hidden Cost of Food

Precision agriculture involves examining every aspect of agricultural production and rooting out inefficiencies. Precision farming techniques involve careful planning, such as consulting detailed maps of soil conditions before planting, and calculating the minimum effective application of resources like water and fertilizer.

In recent years, farmers have pioneered a multifaceted version of precision agriculture. The connected farm uses advanced technology—including GIS—to understand how various inputs (soil, seeds, wind, sun, water) function together. The concept can also involve tools like automation and artificial intelligence to analyze and perform farming operations.

Large amounts of data from IoT devices, satellite or aerial imagery, or autonomous vehicles allow farmers to take a systems engineering approach to agriculture. GIS provides a way to visualize the data in the form of smart maps and to discover insight and predict trends in production. Food producers can use that insight to adjust practices and increase resilience while reducing the cost and climate impacts of food.

The connected farm can be extended to multiple farms to assess best practices and efficiencies, something the US Department of Agriculture is exploring with private sector partners. Through analytic tools such as lidar and satellite imagery, the connected concept can be applied at a global scale.

Strengthening Supply Chains, Planning for the Future

Reducing the real cost of food does not begin and end with growing crops and raising animals. It involves the entire food production system, including the supply chains that link farms with retail stores.

With digitization now common in logistics and fulfillment, GIS-based smart maps are frequently used to reveal weak links in the supply chain. Managers can view problematic sections in context and strategize ways to fix them. Some consultants even use GIS and predictive models to anticipate where climate hazards will threaten future supply chains, helping companies build resilience and avoid risky investments.

As with connected farms, a location-based approach to the supply chain reduces costs by maximizing efficiency. For example, a location-savvy approach to the food supply chain could lower overall costs by reducing spoilage, which causes an estimated $400 billion in losses every year.

Splitting the Bill

The true costs of food are not evenly distributed. The Rockefeller Foundation found the burden disproportionately impacts people of color, immigrants, refugees, and other marginalized communities.

These costs are felt through the higher incidence of diet-related diseases, polluted neighborhoods, food insecurity, and the vulnerability of agriculture and food service workers to COVID-19. For business leaders and policy makers alike, pursuing equity across communities necessitates a geographic approach.

From the supply chain to farms to the communities they serve, a location-smart approach to food production helps companies reduce negative costs and strengthen resilience, so that when the food bill comes due, the price isn’t too high.