The ubiquity of climate change disruptions and the urgency of a green economy are driving financial decision-makers toward a new class of calculations when considering investments and partners.

Estimating returns on logging a plot of timberland may be a familiar exercise—but what’s the value of not logging it, and instead generating offsets to sell in the carbon market? A sugarcane mill located near Costa Rican rain forests might offer low production costs, but board members may ask whether it is worth the reputational risks posed by its environmental impacts. An investment team considering a mining opportunity in Australia might ask how exposed the assets are to the threat of wildfire.

For those holding the purse strings of the global economy, the ability to quantify and analyze the effects of business on nature, and of nature on business, is becoming an essential competitive advantage.

A specialized brand of spatial finance—a term coined by Oxford University’s Sustainable Finance Group—has arisen to meet the demand for such insights.

Spatial Finance: Assessing Sustainable Risk and Opportunity—From Earth and Space

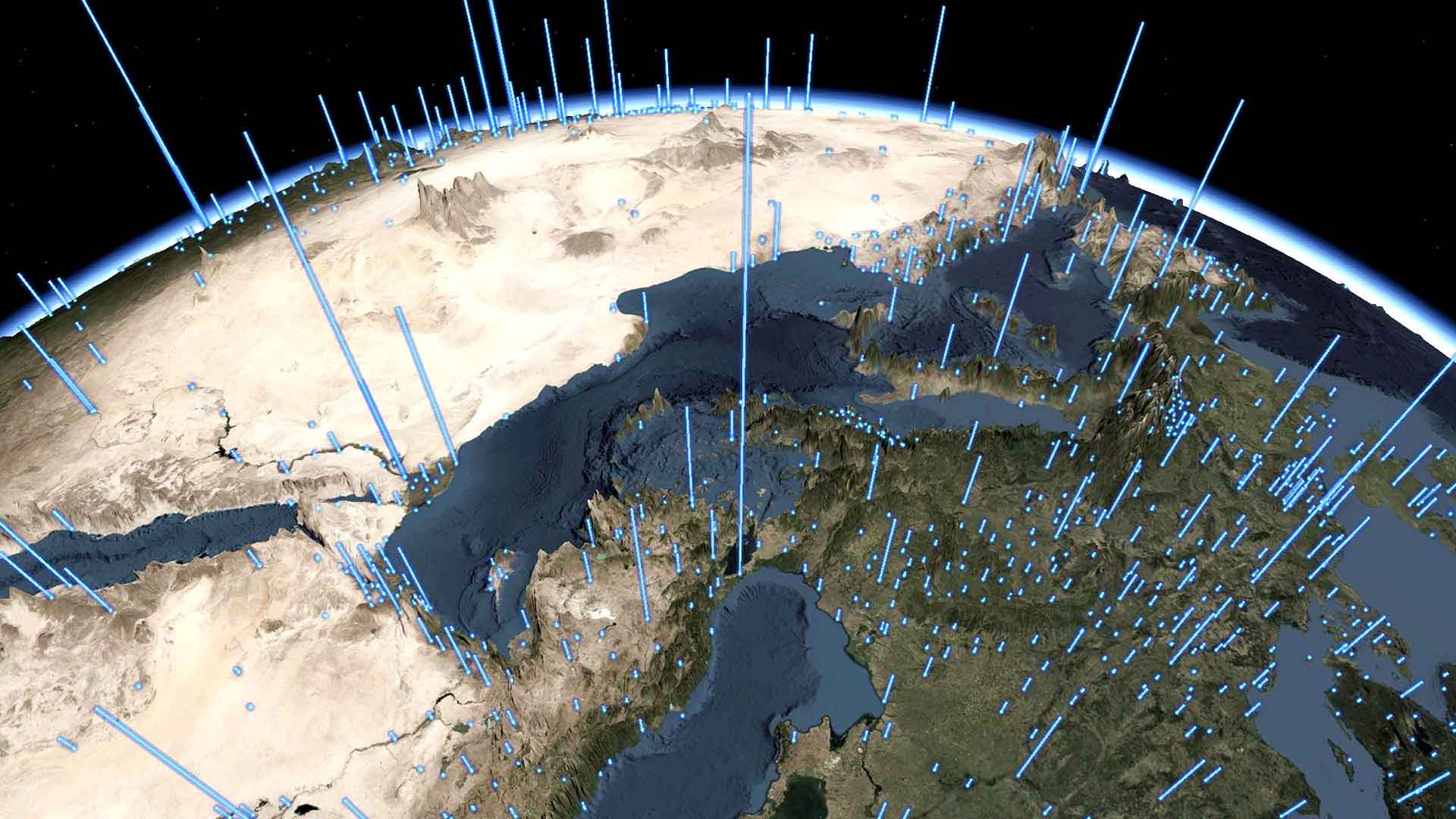

This new application of spatial finance relies on a suite of innovative technologies including a geographic information system (GIS), remote sensing, and artificial intelligence (AI) to generate insights on sustainability-related risks and opportunities in locations around the world.

The near real-time speed of imagery and information generated by satellites, drones, or IoT sensors has made spatial finance attractive to bankers who are well-versed in high-frequency data. Machine-learning algorithms rapidly process images and sensor readings of forests, coastlines, or cropland, spotting anomalies or patterns on a global scale.

GIS enables lenders and advisers to map and analyze these findings via a geographic approach that incorporates business infrastructure, supply chains, and insurance policies. From this holistic operational view emerges a powerful form of location intelligence—one that allows executives to anticipate places where business and sustainability priorities might clash or successfully merge. They can then tailor strategies accordingly.

David Patterson, head of conservation intelligence at the UK branch of World Wildlife Fund (WWF), has seen significantly more interest in spatial finance—and a related practice referred to as geospatial ESG—in just the last six months. “It’s only going to be a matter of time until we see this more and more mainstreamed,” he told WhereNext.

When a company’s sustainability practices—or lack thereof—impair its access to financing, its cost of capital, or its insurance eligibility, sustainability quickly becomes a C-suite issue.

Geographic Location: The Nexus of Nature and Finance

Spatial finance is predicated on the idea that geographic location, the natural environment, and economic outcomes are interlinked. Those who can discern patterns and trends in those relationships—and factor them into decisions about whether to back a startup or write an insurance policy—can minimize losses and safeguard returns.

No less an authority than Adam Smith, the forefather of capitalism, attested to the power of location to influence financial fate. In his landmark tome The Wealth of Nations, Smith notes how countries with access to coastlines, which facilitated trade, outperformed those situated inland. In the 21st century, it matters not only how close a company is to resources, but also how it treats those resources. Spatial finance makes it harder for companies to hide harmful activities.

The practice can be employed by investors and insurance firms to analyze would-be partners or customers.

It can also help companies analyze their own operations around the world and understand areas of risk.

Many firms first turn to spatial finance for help with a pressing need: identifying climate risks, ideally before the worst-case scenarios come to pass. The eruption of wildfires in Australia—estimated to have caused over $4.4 billion in economic damage—was a flash point for the Swiss private bank Lombard Odier. To better assess how such natural catastrophes threaten business assets and infrastructure, the firm engaged geospatial consultants.

By interweaving satellite imagery with data on temperatures, wind speed, and humidity in the affected Australian regions, the Lombard Odier team determined that wildfires could have been predicted using the toolset of spatial finance. As reported in Bloomberg, geospatial analysis is now an input in investment decisions at Lombard Odier.

As investment banks, data providers like S&P Global and Refinitiv, and third-party consultants and watchdogs like WWF dedicate more resources to spatial finance, business executives are taking note. Companies that use GIS software can plumb thousands of data layers that are updated daily or weekly on measures likes heat indexes, water quality, and deforestation. Even a basic geospatial capability can help CEOs anticipate the sustainability-related issues that financial institutions, insurers, and other business partners might flag.

“GIS is the anchor point,” says Pablo Izquierdo, GIS lead for the WWF Intelligence team. “It’s the workshop where you pull everything together.”

Measuring the Imponderables

The definition of spatial finance is broad and can technically apply to any sort of economic indicator that can be measured from space or terrestrial sensors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some investors relied on satellite imagery of Chinese automobile plants to assess economic activity and adjust investments. Hedge funds have used remote sensing to monitor oil inventory levels, lumber supply, and crop yields.

However, the more innovative application of spatial finance today may be its ability to measure traditionally nebulous environmental outcomes, like the carbon-trapping power of untilled soil or the effect of pollinators—or invasive species—on agriculture or timberland. The WWF and others refer to this narrower scope as geospatial ESG.

Financial institutions—which often invest over decades—increasingly recognize the importance of minimizing methane emissions, habitat destruction, and other activities that harm the natural world and heighten climate risks. Their spatial finance analysts rely on advances in data technology and location intelligence to translate those factors onto the balance sheet—or more accurately, the smart map.

“The ability to assign economic values to things—to positive externalities which before had just been taken for granted—that is a key aspect of this discussion,” says Richard Hall, president of Buckhead Resources, a natural resource management and advisory firm based in Atlanta, Georgia.

For example, S&P Global has used NASA satellite imagery to study public water utilities. Analysts determined that utilities sited near ecosystem resources like evergreen forests had better outcomes on debt metrics. Against the backdrop of droughts and growing water scarcity, that kind of location intelligence can influence credit ratings and municipal debt markets.

Finance is incredibly important to how decisions are made and how the natural world is impacted.

A Dual View on the Value of Sustainability

There’s a longstanding history in natural resource industries of using GIS to manage and track key data and information such as timber inventory or real estate values, says Hall, who also serves as an instructor of natural resource finance at Auburn University. With GIS that uses AI to contextualize satellite imagery and data gathered from sensors, investors, insurers, lenders, and other stakeholders can now take into account what are known as “ecosystem services.”

The term, popularized by the United Nations-sponsored Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, identifies the benefits that society and the planet derive from healthy ecosystems like woodlands, wetlands, coastal reefs, and mangrove forests. Rather than seeing trees only in terms of the dollar value of timber, firms like Buckhead Resources use spatial finance to also quantify a forest’s value as a carbon sink, as a source of revenue from hunting or other recreational activities, or as a natural bulwark that prevents soil erosion.

The dual view afforded by spatial finance helps Hall offer landowners, timber companies, and other clients guidance on complex questions. By analyzing metrics like soil and water quality and nearby transportation infrastructure in a geographic context, he can advise a company on how to optimally manage land for a combination of uses including commercial forest management, mining, or conservation. The same analysis can extend to forestry and other natural resource firms that are exploring a transition from land use focused on natural resource management to uses such as real estate development, infrastructure, or renewable energy.

For Hall, who opened his firm just two years ago, GIS’s data and analytical capabilities are the linchpin of spatial finance, and help generate the kinds of insights that might normally come from a much larger firm. “We’re able to do so much more than we could do otherwise by leveraging our abilities with a powerful GIS platform,” he says.

Being able to visualize and effectively manage with a good GIS package is critical. But [just] as important as being able to visualize it [is] integrating that spatial data with the financial data.

Gaining Visibility on Regulatory Risk

Another area where spatial finance is fast gaining traction is in policing reputational and regulatory risks. Many financial contracts these days include environmental, social, and governance (ESG) guidelines around measures like carbon emissions. For multinational companies and the banks and investors that provide them financing, lack of transparency on supply chain impacts or the actions of business partners can trigger fines and damaging headlines.

“There’s huge demand from financial institutions to better understand what’s going on,” says WWF’s Patterson. “There’s a lot of regulation coming on top of them. They sign up to these agreements and, in many cases, they struggle to understand if they are complying to those agreements.”

For instance, a bank that adopts the Equator Principles, a major benchmark of socially responsible practices for financial institutions, has to consider the impact of loans on critical biodiverse habitats. With a GIS-powered dashboard, bank executives can leverage remote-sensing data to monitor where companies in their portfolio might be operating in proximity to protected sites.

“The smart actors I see now are the ones who are closely watching developments, preparing and building capacity, hiring the right people, and are already there demanding access to asset data and better environmental data,” Patterson says.

To Grow, Protect, and Preserve

It’s telling that many of the places on earth that have the highest levels of biodiversity also tend to be rich in natural resources; healthy ecosystems foster the ideal conditions for natural life, and economic opportunity often follows.

Guided by the geographic context of location intelligence, spatial finance and geospatial ESG help stewards of capital find a balance between capitalizing on earth’s rich bounty and protecting it for future generations.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

April 1, 2025 |

February 1, 2022 |

April 29, 2025 |