The path from raw material to finished good to a customer’s home is carefully choreographed. Less so? What happens when that ill-fitting pair of pants or unwanted gadget ends up in the return pile.

What some companies are discovering, however, is that the location intelligence they rely on to deliver products to customers efficiently can be equally helpful when goods move in reverse—an increasingly common occurrence.

As consumer spending has grown, so too have product returns, more than doubling between 2019 and 2022 to an estimated $816 billion annually, according to the National Retail Federation and Appriss Retail. While returns can be a convenience for consumers, they’re less convenient for company balance sheets and the planet. Some returns can be resold in stores, off-loaded to discount resellers, or donated to charity, but the rest often end up in incinerators or landfills, according to a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed by a pair of University of Tennessee logistics experts. That creates about 6 billion pounds of landfill waste and 16 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, the authors said, citing a study by returns-management company Optoro.

Frustrated by the financial losses and environmental degradation created by returns, some companies are eyeing a circular economy approach—one that connects them with interested buyers or manufacturers that can create something new from what’s been returned.

Connecting Product Returns with Sources of Demand

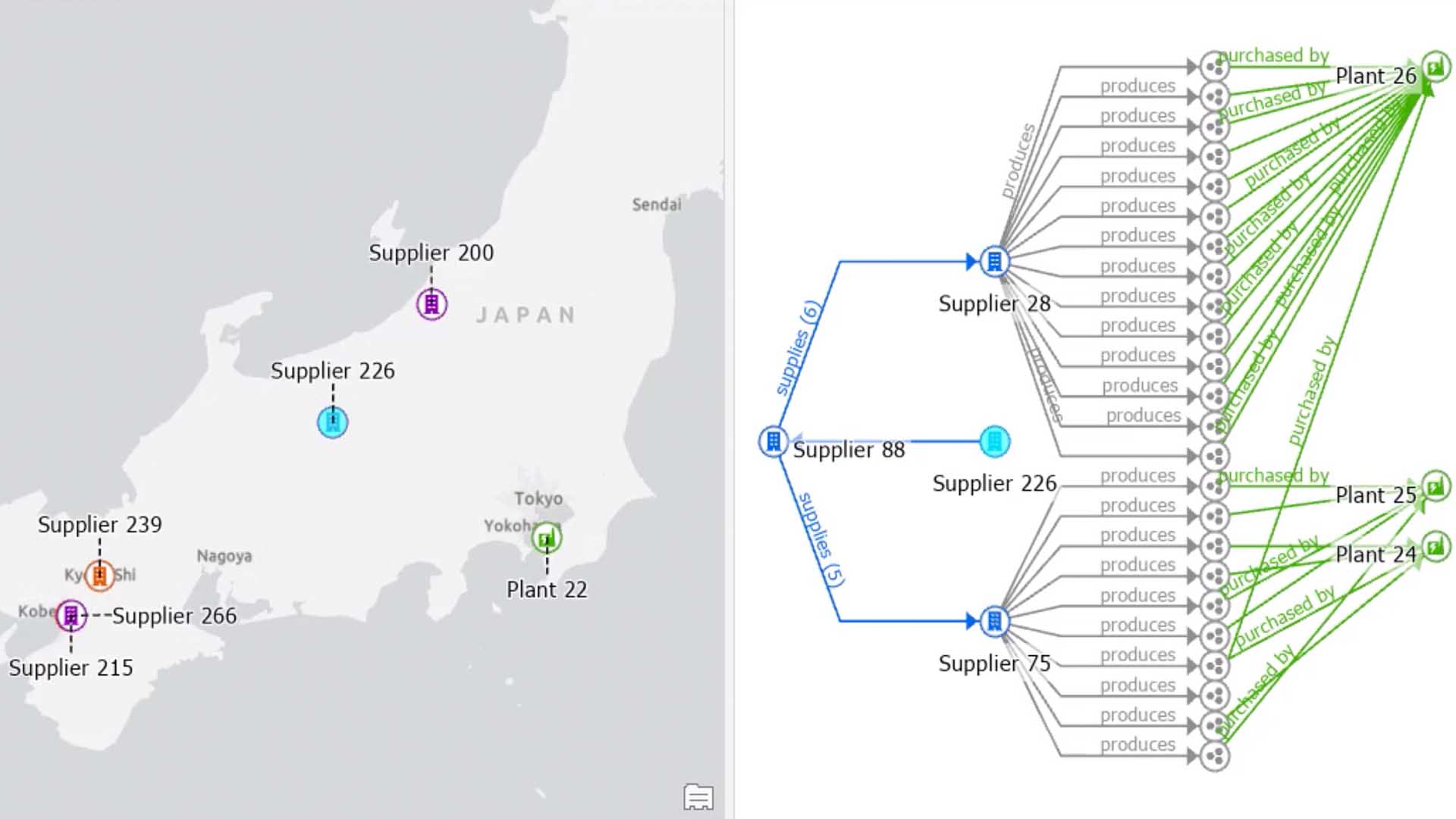

One challenge of reverse logistics is that there’s far less predictability about where returns will go than there is in a typical supply chain. What can make the process clearer is a smart map that reveals the location of products and their potential destinations. For goods that will end up back on store shelves, GIS technology can capture real-time location information from inventory management systems, indicating which stores in the retail network need certain products. For returned goods that can’t be sold in store, a smart map can show facilities that take donations or resell returns.

Then there’s the opportunity to convert returns into new products through upcycling. At a time when supply chain disruptions have left companies scrambling for key components, materials can be harvested and used to make repurposed furniture, apparel, and other goods. That circular economy practice aims to lengthen a product’s useful life, reduce waste, and preserve—even revive—natural systems.

As noted in a recent WhereNext article:

From an environmental perspective, the consequences [of disposal] are increasingly significant, impacting air, water, and soil resources that underpin the economy. For business executives, trashing products that could be repurposed and resold violates a basic tenet of profitability: never leave value on the table—or in this case, at the dump.

One company is using GIS technology to manage the circular economy for plastics. By assigning plastic products a unique digital identifier, the company can use a smart map to trace each batch from the point of collection to the recycling facility and beyond. Such transparency helps manufacturers validate net-zero achievements while giving consumers confidence that their purchases are supporting the circular economy.

Pinpointing Supply Chain Links in Proximity

Once a company identifies organizations interested in buying returns, planners can use location intelligence to better route the products.

GIS software identifies logistics routes that minimize miles traveled and carbon emissions, whether by ship, train, truck, or plane. GIS specializes in complex analysis and coordination, helping companies like FedEx orchestrate the movement of spare parts to keep its planes airworthy and minimize waste in the system.

Establishing the links that turn product returns into circular opportunities is inherently a geographic pursuit. Ultimately, this geography of reverse logistics can help build a circular economy, increasing both sustainability and profitability.

Photo by Sigmund

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

March 18, 2025 |

May 28, 2025 |