Even as population growth slows, projections show that the world will be home to nearly 10 billion people by 2050, 2 billion more than it hosts today. The job of feeding them will fall to an industry that’s emerging on the forefront of innovation.

Farmers are getting younger and more tech savvy, and they’re transforming the agriculture industry through location intelligence and tools such as AI, autonomous vehicles, and IoT-connected cattle.

In this installment of the WhereNext Think Tank series, Esri’s director of Professional Services, Brian Cross, interviews Esri’s agriculture practice lead, Matt Harman.

Brian Cross: In this series, we’ve talked about how businesses have been impacted by the next generation of location technology. I’d like to turn our attention to something you know quite a bit about, which is the agriculture industry.

Agriculture is a type of manufacturing, but when you’re growing soybeans or maintaining cattle, you’re dealing with a lot of conditions you can’t control. Could you speak at a high level about how technology is helping in this production environment?

Matt Harman: Fields and vineyards are definitely a more dynamic environment than what you find in a typical manufacturing facility. We’ve seen farmers cope with that in different ways over the generations. Today’s growers are creating the connected farm, ranch, and vineyard.

The connected farm is a broader vision of precision agriculture, which has been around for decades. Technology plays a key role—it’s changing how farmers look at a field of corn or the next crop of grapes or a herd of cattle. With new technology and data, growers and ranchers see in a very nuanced way how each location within their operation is performing and adjust proactively.

Planning and Planting with Location in Mind

Cross: That’s an interesting concept—a connected farm that’s location aware. Can you give us an example of what that looks like?

Harman: Seed selection is a good place to start. All the big seed companies research hybrid seeds, and now they’re able to capture more performance data than ever—through IoT sensors, drone-based imagery, automated field equipment, AI technology, and other tools. That creates a ton of information that helps them understand what seed is going to perform best in which location. And not just where but when, too—it tells them when to plant a seed to capture the right amount of growing-degree days.

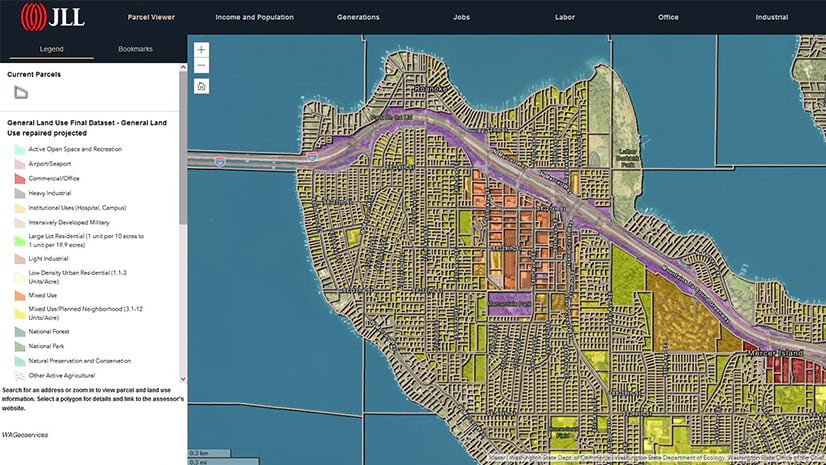

This information traditionally hadn’t been available, at least not with such precision. So farmers are using GIS technology and smart maps to learn location-specific insight they couldn’t see before. That’s just one aspect of the location-aware farm. It’s getting more sophisticated every day.

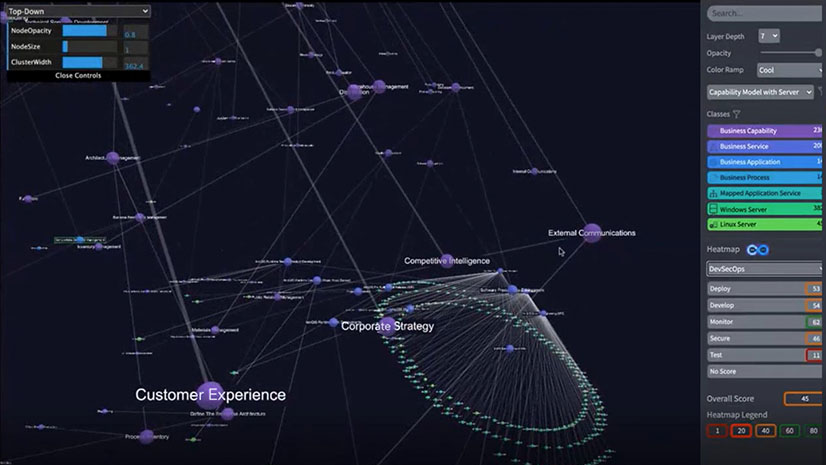

Precision ag is about deciding what to plant where. A connected farm is much more than that. It's fieldworker enablement, crop monitoring, surveillance, IoT devices. And it's coming together in a single pane of glass that lets you manage the farm.

Creating a Location Dashboard for the Connected Farm

Cross: If you pan out a bit, I imagine there are many ways farm managers are planning and monitoring operations better. What kind of techniques are they using?

Harman: We’ve worked with IoT-connected cattle, automated harvesters, smart drones, and other new technology. I had a conversation with a vineyard manager who said, “Look, I want to manage my ranch tightly, task the right people to do the right jobs at the right time. But I also have a condo at the beach, and I’d really like to do all that from there.”

He had the technology to do it—soil sensors, irrigation systems, weather stations in multiple locations, even drones with infrared sensors that show where grape health is bad and good. What he was missing was a single view of all that information. He had to log in to too many point systems to make decisions.

The conversation started off as something of a joke, but the more we talked, the more it became clear he needed a single map or dashboard that he could pull up on his iPad. His vineyard was connected; we just needed to make it locationcentric. He realized location is the ultimate integrating concept.

Cross: That ties back to what we see in other industries. We did a Think Tank segment called “A Single Pane of Glass,” which was about corporate security. We looked at how companies bring information feeds into a smart map or dashboard to create a global perspective and make quick decisions. Even though the industries are completely different, it’s striking to see the similarities in how they use location intelligence.

Coordinating Field Operations

Cross: I’m curious about another trend we’re seeing in many businesses, which is optimizing fieldwork. A lot of utility workers, truck drivers, and other service providers are more efficient today because they’re connected through mobile devices. Is that happening in agriculture as well?

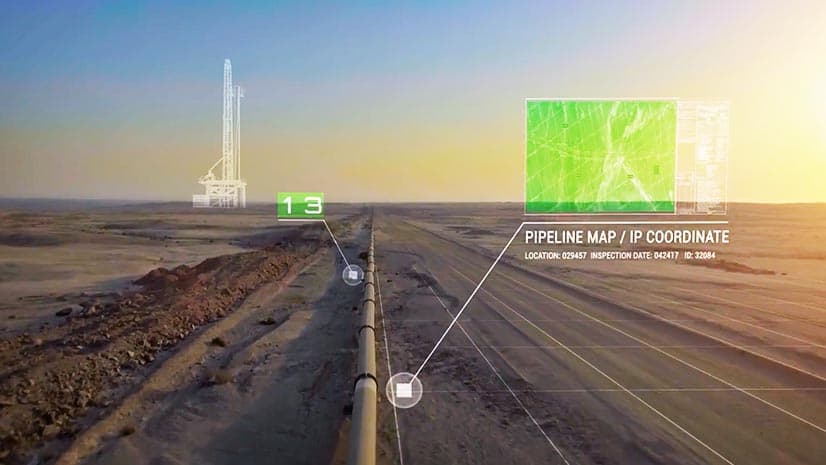

Harman: It is. I’ll give you the example of a company that delivers fertilizer to a farm, using center pivot irrigation—the large boom on wheels that goes around in a circle and irrigates the field. At certain times during its rotation, the boom blocks access to the road. And it moves so slowly that the delivery truck might wait for 45 minutes. That wastes the fertilizer company’s time and jeopardizes its other deliveries.

With GIS, we have a real-time map of where the boom is and when it will block the road. So we send push notifications to a mobile device that shows the driver a map, saying, This road will be inaccessible from this time to this time—we’ll notify you when the path is clear.

Cross: What about some of the more traditional fieldwork that takes place in agriculture—how is technology changing that?

Harman: For crops that are manually harvested, some companies are working on bots that actually do the picking, but that hasn’t been perfected. Fieldworkers are still the backbone of the picking process. Now their mobile devices are helping them create crop traceability. Traditionally, if you had a large plot of land with many planting locations, you couldn’t tell where a specific piece of produce came from on the farm. That information can be important if there’s a contamination issue—and also in figuring out which growing conditions produced the best-tasting produce.

So farms are starting to combine mobile devices with smart maps. Now the pickers are the sensors. If they’re wearing a smartwatch or have a cell phone with tracking enabled, the farm manager can see on a GIS map where that picker was and when they picked that produce. That can help isolate contamination issues so food isn’t unnecessarily destroyed, and it can help farmers identify their best produce so they can repeat that success.

Artificial Intelligence Takes Root, Drones Take Flight

Cross: You’ve talked about planning, growing, operating, and harvesting. I’m curious how artificial intelligence is playing into these workflows.

Harman: AI-based robots that are spatially aware and can navigate through a field to pick produce—that’s definitely an application under development. There’s a lot of investment in bringing that to reality.

Another frontier is the combination of drones and AI to detect crop health and damage. Farmers can fly drones and use artificial intelligence to “read” the imagery and understand where there’s a certain problem. That saves them from having to send fieldworkers in to do crop scouting, and it allows them to quickly isolate an issue.

Insurance companies are flying drones over fields to do a quick damage assessment, cut a check, and get the farmer back on their feet. The drones use artificial intelligence to distinguish crops that have been damaged by hail, for example, from those that haven’t.

Machine learning models are also crunching data to help with planning. Farmers and seed companies are taking historical weather data, past yield performance—any information they can gather—and feeding that into location-intelligent systems that are constantly trying to determine where to place the next seed. GIS provides the smart maps that make sense of the results.

Cross: What about forecasting, the practice farmers have been obsessed with since before the days of the almanac? How is it changing?

Harman: Forecasting has always been important—it’s key to balancing supply and demand. Farmers are assessing the conditions of current crops, analyzing the weather forecasts, and layering that data with historical yield data to make a determination of what they’ll send to market.

Some companies fly their fields with drones or aircraft toward the end of the growing season to analyze the vegetative index and get an indication of what the yield will be. That allows them to tell the grain elevator that they’re anticipating 5,000 bushels of corn, for example. And then they can plan for how many combines and how many tractor trailers they’ll need to process it all.

Artificial intelligence models are combining with GIS technology to help these farmers plan ahead.

Like any commercial business, agriculture is about managing inputs and outputs to maximize return on investment. Location-aware farms understand conditions better and make more effective adjustments.

The Digital-Native Farmer Drives Ag Innovation

Cross: You’ve talked a lot about innovation. If we step back for a minute, what’s your sense of farmers’ willingness to change and adopt new technology? Is the next-generation farmer a digital native?

Harman: Absolutely. And they’re hungry for technology. I was joking with a friend recently about the old height requirement for tractors and combines. You just had to be at least this tall to drive them. Now you need a college degree.

On a connected farm, advanced technology is everywhere, and it’s completely location enabled. Farmers are measuring where things are planted, if they’ve been double planted, what’s been harvested, and how much yield specific locations produced each year. They analyze the diagnostics from the equipment, the elevation of certain plantings, the slope the equipment is on. They track the sun, the weather, the water and fertilizer—all the conditions specific to their fields.

It’s a data-hungry, technology-hungry industry. A lot of farmers are more tech savvy than your average city dweller.

Where Next for Smart Ag?

Cross: With all these innovations on the connected farm, what’s left for farmers to improve?

Harman: We’ve had a few conversations about how blockchain technology might improve things like agricultural traceability, recalls, food spoilage, and supply chain efficiency. As the connected farm continues to evolve, I think we’ll see that technology become more interesting to farmers and their supply chain partners, including retailers.

In general, the thirst for insight is going to keep pushing farmers to innovate. We’re already seeing cattle and pigs connected to the IoT, for example. Farmers are monitoring their health and location via RFID tags. It just shows you that ag people are innovators. And that anything that can be monitored on a connected, location-aware farm soon will be.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

August 5, 2025 | Multiple Authors |