Not long ago, Newmont, the world’s largest producer of gold, faced a corporate challenge that could affect all aspects of its global operations. Across the business world, companies were increasingly focused on environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) issues, and Newmont, which initiated a corporate ESG program nearly a decade ago, wanted to further distinguish itself as an ESG leader in the natural resources industry.

One of its challenges: How could the company more effectively manage and monitor waste products, called tailings, created from the processing of ore? And how could it do so without impairing output, damaging the environment, or significantly affecting the bottom line?

As global demand for precious metals continues to rise, “building and managing these facilities properly becomes significantly more important,” says Mark Casper, vice president for resource evaluation and mine planning across Newmont’s operations in North America, South America, Australia, and Africa. “Because effective management of our liabilities is what will differentiate mining companies moving forward, and the more we raise our game, the more influence on other producers to do the same.”

New Tools for the Ancient Work of Mining

Tailings consist of a slurry of ground rock and chemical effluents that are generated in the process of separating a precious commodity from ore. The tailings slurry is deposited in an outdoor containment area called a tailings storage facility that is often surrounded by earthen embankments and engineered to be both structurally and environmentally safe.

Newmont uses a geographic information system (GIS) to locate mineral resources, much as other companies use GIS to scout for energy deposits or plan wind farms. Once a tailings storage facility has been constructed, operations managers typically use GIS-based software to monitor on-site sensors and track the facility’s performance as part of a broader monitoring program.

The company’s commitment to improving the sustainability of tailings management was in part an acknowledgment of the practice’s wide reach inside and outside the company. “It touches the communities [where Newmont works],” Casper says. “It touches the environment; it touches the rest of the business. [And] occasionally, we may need to make trade-offs that may be slightly detrimental to costs and performance in the operation to make sure we’re doing the right things on an ESG platform. And we’re committed to addressing those challenges head on.”

Two years ago, Newmont found itself in need of a global leader to oversee and refine tailings management—someone who would further strengthen risk management practices to ensure the safety of Newmont’s sites and neighboring communities. That person, Casper notes, would start with the premise, “We will get this done,” then push forward without taking no for an answer.

She would need the authority, experience, and social skills to manage complex internal discussions, and the ability to raise expectations without alienating colleagues. Kim Morrison fit that profile exceptionally well.

The Right Person at the Right Time to Elevate Tailings Management

A geotechnical engineer and former consultant with significant experience in working with mining operations, Morrison possessed deep industry knowledge, a clear vision, and the social skills to negotiate complex corporate networks. As Newmont’s senior director for global tailings management, her mission and vision include strengthening the methods and standards for dealing with ore-processing waste, improving monitoring through the use of GIS and location intelligence, and evangelizing the importance of those efforts throughout the mining industry.

“We needed somebody that could really [raise] the profile of tailings design and management within the business,” Casper says. “And Kim certainly fits that bill. She’s got a great eye for detail. She does tremendous amounts of work and the quality of work is great. She just ticks all the boxes.”

Casper adds a note that isn’t found in many job descriptions. “Probably the biggest factor is she is absolutely passionate about this. There are no ifs, ands, or buts that this is one of the things that she was meant to do, and she goes after it.”

Having worked on tailings management in other jobs, advocated for higher levels of monitoring, and earned the respect of colleagues in the natural resources industry, Morrison arrived at Newmont excited for the opportunity.

Leading Efforts to Improve Operations

Morrison was hired to see that Newmont was not “just reaching the bare minimum of what we want to do,” Casper says, “but making sure that we reach the levels of practice in tailings management that are going to take us to the next level.”

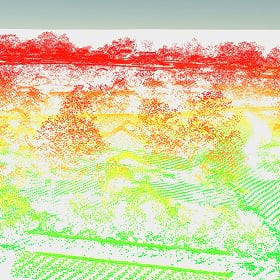

Under that banner, Morrison began working to strengthen location intelligence for Newmont’s tailings facilities. Her vision was to create something of a digital twin of each facility—a real-time network of sensors that managers could monitor on GIS maps. The system will include sensors that monitor embankments and dams for changing conditions, track water levels and deformation, and send alerts if readings reach prescribed trigger levels.

Morrison also sought to create global visibility to tailings management across Newmont. That means establishing GIS dashboards tracking the status of the facilities Newmont oversees around the world. The upgraded system will also incorporate drones, some equipped with thermal imaging that can detect conditions in the earthen embankments that could lead to seepage—before it is visible to the human eye.

“My desire is to have visibility to facility performance at my fingertips for any of our worldwide facilities and at any point in time,” Morrison says. “We’re currently in the process of expanding our use of real-time monitoring of our facilities, and we’re working to explore linkage of the drone data with the data from instrumentation and remote sensing sources to support development of the desired four-dimensional view.”

The fourth dimension is time. In this case, that includes the past performance of tailings containment areas. Morrison learned the power of historical data from a GIS specialist more than a decade ago when she saw how data could be transformed and compiled in a map-based platform to provide a complete picture of a site’s characteristics, and how this significantly improved data presentation to support federal permitting efforts for expansion of a US tailings facility.

Morrison has applied that knowledge to her current work. “We have developed and are in the process of implementing new standards and guidelines for tailings management within Newmont,” she explains. “We are implementing training programs and workshops to support competency building of our personnel.”

In a fast-changing field that demands safety and environmental stewardship, it’s important to make sure everyone stays current. “We implemented monthly global team meetings to keep our sites up to speed with new developments, while providing a platform for learning from each other,” Morrison says.

She and the team have implemented a web-based application for monthly reporting of critical control performance for tailings facilities—a report that reaches the highest levels of the organization.

In two short years, she has witnessed positive change, especially in the visibility of the practice at the company’s highest level. “I have seen a paradigm shift within the company with respect to tailings management over that period,” she explains, “and I’m proud to be a key contributor.”

Morrison's vision was to create something of a digital twin of each facility—a real-time network of sensors that managers could monitor on GIS maps.

Injecting Urgency into the Industry

Morrison, who was named one of 100 Global Inspirational Women in Mining (WIM) in 2020, has been working hard to find people outside the company who also are driven to increase the sustainability of tailings management.

Casper describes her as “passionate about spreading that influence to the broader industry.” She is active in industry consortia, including the Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration (SME) where she is the founding chair of the Tailings & Mine Waste Committee, leading development of a comprehensive tailings management handbook, an external tailings information portal, and webinars and programs. She also serves on the tailings working group of the International Council on Mining & Metals, and was an active contributor to ICMM’s Tailings Management: Good Practice Guide.

Morrison believes the mining industry and the next generation of operational leaders are taking notice.

“It is very much [a] growing field,” Morrison says. “With the GISTM [Global Industry Standard on Tailings Management] that spells out certain requirements around governance and roles and responsibilities, the future of tailings management for young professionals trying to figure out what they want to do is very, very bright.”

Women in STEM Taking on Mining’s Environmental Challenges

Briana Gunn, director of environmental affairs at Newmont, has been a long-term advocate for Morrison. Both work in a STEM field dealing with vital but challenging environmental issues.

Gunn credits Morrison’s success at the company to her firsthand experience at mine sites and her clarity of purpose. For instance, during one important planning meeting about improving tailings management, some managers were focusing on past issues. Their complaints were legitimate, but distracted from the discussion of how to move forward. Gunn recalls the scene.

“The meeting was kind of going sideways, and Kim said, ‘Let’s take a step back and let’s just understand exactly what the condition is that we’re working in now. What’s the existing status [of tailings]? What is this risk we’re concerned about? And I think that will help us make the decision,’” Gunn relates.

The managers stopped, realized they had drifted, and refocused on the agenda.

“It is Kim’s strategic level of thinking and practical operational experience that make her a valuable asset to Newmont and the mining industry in general.”

“I Think We Can Do Better”

The results of Morrison’s dedication are hard to miss, Gunn says. “We were doing tailings management before she got there, but not at as high a level as we’re doing now . . . and not elevating and communicating the important issues throughout the organization.”

Along with technical know-how and personal energy, Morrison has another essential element that wins supporters: her integrity.

“It’s her ability to look at a situation and say, ‘I think that we can do better, and we need to improve our systems,’” Gunn says. “And her willingness and her drive to do that is what I would call her integrity.”

That drive, combined with an appreciation for the role of GIS and other technologies, has made an impact at Newmont.

“We needed a real hard look taken at our governance around [tailings],” Gunn says. “It was extremely valuable to have somebody take a look at it and say, ‘Let’s figure out how we can better integrate risk management into our design, into our governance, into the way we evaluate projects.’ And while there’s still work to do, she’s done a lot in the two years since she started.”

Always Driving the Project Forward

Where did Morrison get the drive and confidence to take on complicated corporate tasks? The answer seems to be found in her childhood.

“I grew up on a farm, one of four children—[a] very supportive family, very supportive parents. I had everything that I needed, but I had nothing extra. And so, I believe that I have a very strong work ethic, and I think that much of that is rooted to my upbringing.”

For fun, her family would compete in hay-bale tossing competitions in their small community about an hour west of St. Louis, Missouri. It was on the farm that Morrison saw the value in being a good steward of the land—by embracing responsible practices that ensured sustainability over the long term.

Those early catalysts eventually helped shape a business professional with the right energy, judgment, and willpower to improve the practice of tailings management at Newmont.

Casper appreciates the results.

“I’ve always said, as a leader, I would much rather have somebody that I need to pull back on occasion than somebody I need to [motivate to] get moving. You don’t have to worry about that with Kim. She’s got ultimate drive and energy to get things done.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

April 1, 2025 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

April 16, 2024 |