Many CEOs thought 2023 would usher in a widespread return to the office. Yet employment trends suggest that the future of work has diverged from pre-COVID-19 norms.

Recent data shows that about half of office workers in major US cities are now spending some days out of the office. Meta and Google, whose posh offices were long considered a draw for tech talent, have introduced plans for desk sharing. In some cases, building owners are repurposing office space for lab work or logistics.

In light of these developments, business leaders are searching for answers on two fronts:

- In the hybrid work era, how can a company optimize its use of space and help employees get the most out of their office visits?

- How will trends like remote work impact long-term capital planning and the physical footprint of a business 10 years from now?

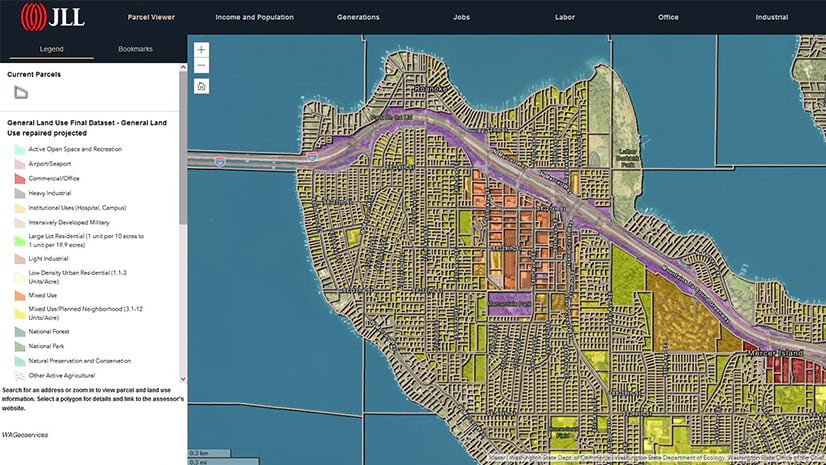

Many executives are turning to spatial insights from geographic information system (GIS) technology to navigate the complexities of modern workforce planning. At Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL)—an epicenter of scientific research and discovery—GIS is helping the organization adjust to a hybrid workforce and expand to foster the next generation of cutting-edge research.

Location Intelligence for a Growing Workforce

Nicknamed the “smartest square mile on Earth,” LLNL’s main campus in Livermore, California, houses more than 500 buildings and more than 6 million square feet of space, including the National Ignition Facility, where scientists accomplished a groundbreaking achievement in fusion energy last year. Over 8,000 employees use the lab’s facilities, working on projects that range from nuclear deterrence to climate resilience.

While other organizations are using location analysis to plan office contractions, LLNL is in the midst of a building boom, with seven new office buildings and several laboratory facilities planned over the next few years. As hiring has accelerated to keep pace with advances in fields like fusion energy, the lab now employs more people than it has space for.

LLNL’s use of GIS—first embraced in 2017 to manage office moves—has evolved to facilitate the growth, helping leaders plan for the decades ahead.

“We’ve gone from really nothing to a state-of-the-art GIS system that is supporting our facilities and infrastructure group—and then growing beyond that because of the goodwill and the relationships we’ve built throughout all these projects,” says Dan Debus, team lead for the lab’s site operations.

For organizations that occupy a leading-edge research campus or a downtown skyscraper, location intelligence has become key to optimizing physical space as patterns of work change.

A Living Map of Campus

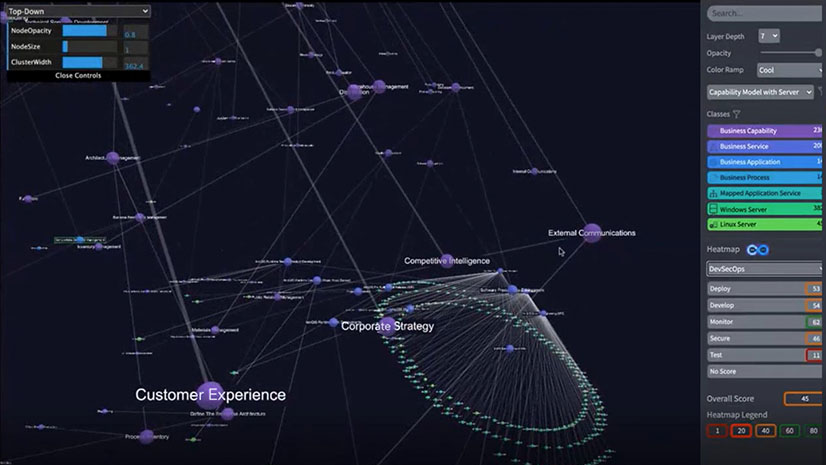

COOs and HR executives in the post-COVID era need a common operating picture to understand the spatial dynamics of hybrid workers and offices.

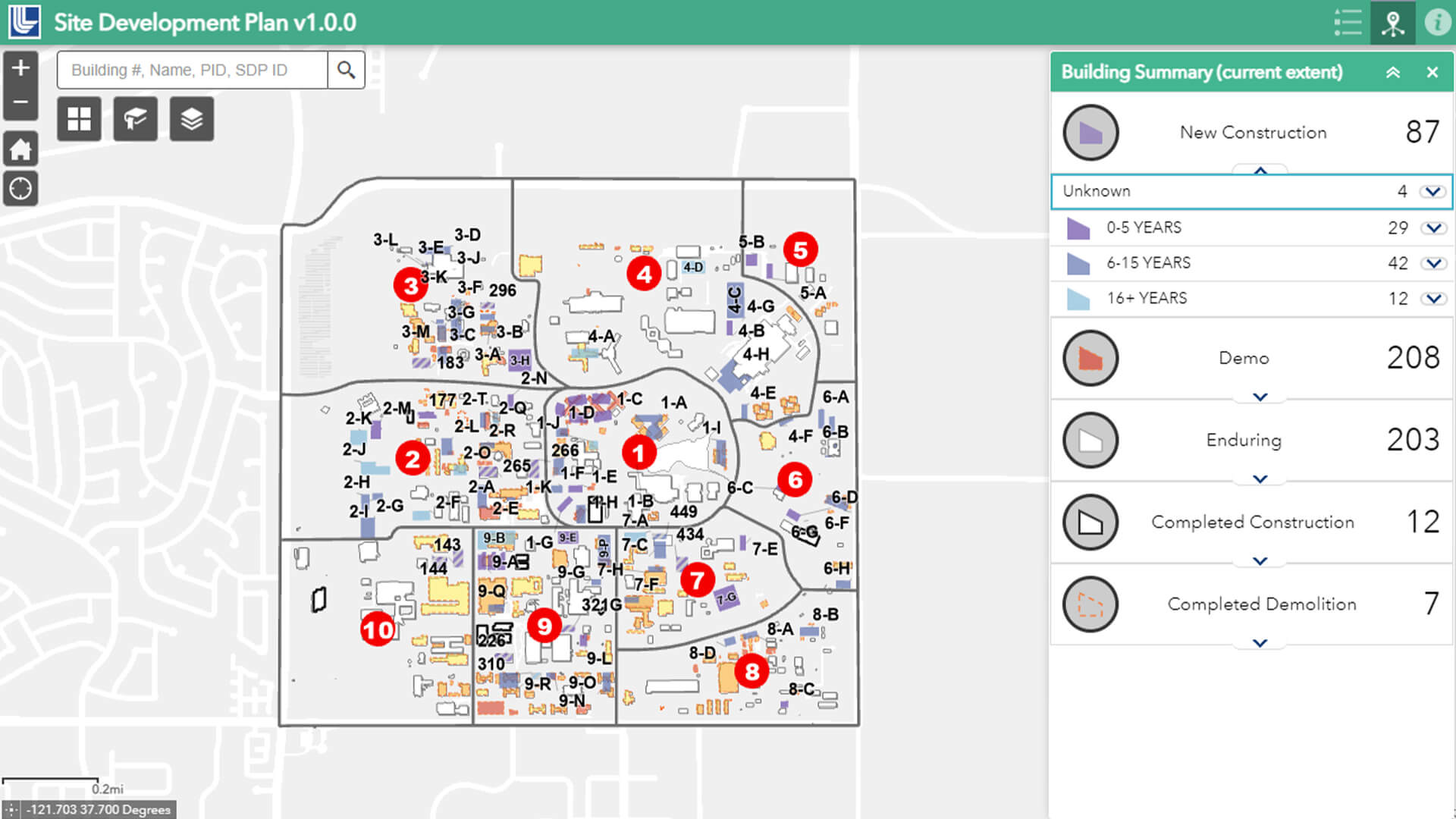

At LLNL, GIS serves as a system of record for multiple business units, revealing the location of assets on campus. Hybrid employees use a hoteling system run by GIS to reserve space near coworkers or book a desk with the right docking station. The space management team uses location technology to analyze occupancy patterns and relocate growing teams to open offices. The site operations team makes GIS models of subsurface utilities for high-pressure gas lines, and tracks which buildings require specific types of security clearance (see sidebar). Senior management relies on a “living map” of the campus, updated in real time, to envision how the lab will grow over the course of decades.

Location intelligence gleaned from the site development map gives lab leaders context as they prioritize construction to meet LLNL’s 10- or 20-year vision. The ability to simulate current and future configurations of the campus helps planners decide whether buildings should be renovated, torn down, or built to accommodate a new lab facility in 2030, for instance. That spatial data, in turn, helps the lab’s leaders justify funding requests to the Department of Energy as the campus evolves.

“It helps them make a very compelling argument when . . . talking about funding,” Debus says. Leaders “have a GIS representation of the laboratory to make their case.”

Where we are headed is a 3D digital twin. . . . When you factor in how we're planning how the lab will look in decades, you could argue that really the fourth dimension of time comes into play as well.

Defragging the Lab

The lab’s GIS maps are built on a foundation of spatial awareness that originated years ago. Before the adoption of location technology, managers lacked a holistic picture of the campus to guide office moves and space management strategies. Now, GIS has become the central platform for campus planners to determine where to place employees across LLNL’s square-mile footprint.

Building a map that could be trusted by the lab’s many stakeholders required an intensive data-truthing effort. Members of the site operations team walked through every building on the main campus, ensuring that each facility matched the GIS data associated with it. They even checked that room numbers were correct.

The resultant map helped planners “defrag the lab,” creating more efficiency and eliminating redundancies like multiple satellite offices for a single employee.

“It’s very influential in telling the story of how we’re using space when you can put a map up on a screen, show a building or multiple buildings across the site, and say, ‘This is what our occupancy is. This is how much space we have that is empty,'” Debus says.

When the pandemic hit, LLNL had the technology in place to adapt virtually overnight. Tom Lopes, a GIS analyst on the site operations team, worked with Debus and others to develop an employee check-in map. This allowed LLNL’s leaders to monitor the concentration of essential employees in buildings, detect early signs of overcrowding, and find empty spaces where workers could expand. It all worked because of the team’s initial data verification efforts, says Jennifer Hopping, a campus planner at LLNL who works closely with the site operations’ GIS team.

“Trueing up that data really helped us establish a source of truth for our occupancy, and without that we would not have been as successful in the response to COVID-19,” she says.

We've really taken GIS from being this, I think, "nice to have" to being something that's absolutely considered critical to the institution.

A Data Life Cycle to Keep Pace with Facilities Management

The GIS applications LLNL developed in response to the pandemic formed the basis for the hoteling technology used by the lab’s hybrid workers today. Similarly, the maps created to improve move management have matured into a real-time digital twin that’s supplanted the annual campus survey, which routinely became outdated soon after its completion.

These upgraded processes illustrate how organizations can create smart maps that track and analyze data throughout all stages of a facility’s life cycle.

At LLNL, GIS helps senior management visualize where and how the campus will grow and the level of funding needed for the next stages of construction. Once a new building is up, it’s added to the site development map and becomes part of the overall picture that informs campus planning.

Amid the many changes LLNL has experienced over the last five years, Debus, Lopes, Hopping, and other colleagues have kept pace with growth and the challenges of a hybrid workforce by deploying GIS applications that scale with the lab.

“We really needed some kind of system that could look holistically at the site and register occupancy as a whole, and that’s kind of what stemmed this,” Hopping says. “Out of this one little plant, we’ve created this whole garden of different maps and an array of different sources that can be connected to make this visualization tool as successful as it is.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |