In 1963, geographer Roger Tomlinson began using computers to organize and analyze over 1,000 maps for a land inventory project in Canada. He coined a name for the software that could digitally catalog spatial data: a geographic information system (GIS).

Sixty years later, GIS is a keystone enterprise technology for the private sector. Across more than three-quarters of Fortune 500 companies, the location intelligence produced by GIS informs the decisions and actions of CEOs, supply chain managers, architects, insurance adjusters, delivery drivers, sustainability officers, and countless other professionals.

GIS enriches data housed in enterprise resource planning (ERP), customer relationship management (CRM), supply chain management (SCM), and its own core database to answer questions at the heart of the modern enterprise.

- Where are our assets most vulnerable to climate risk?

- How do we manage operations across our enterprise?

- What are the best locations for our retail stores?

- How can we predict sales in upcoming quarters?

Through the decades, GIS evolved to take advantage of technological advances—from mainframes to modern supercomputers, satellite imagery, and AI-based predictions. Companies came to embrace GIS as an enterprise technology, making it a go-to resource for corporate leaders to understand where things happen, analyze and predict business impacts, and take informed action.

To understand how a technology originally developed for land management found a loyal following among today’s business analysts, managers, and executives requires a dip into the past.

1970s to 1980s: Finding a Foothold in Natural Resources

The earliest users of GIS were state and federal government agencies. However, commercial enterprises weren’t far behind in recognizing the potential of location technology.

In the business world, natural resource companies were the first to embrace GIS. Forestry firms adopted the software to track and manage their land—much as Tomlinson used the first GIS for the Canadian government. Maps were an elegant way of organizing data like property boundaries, ownership records, and environmental considerations.

Other resource-focused companies followed as the technology’s analytical capabilities improved.

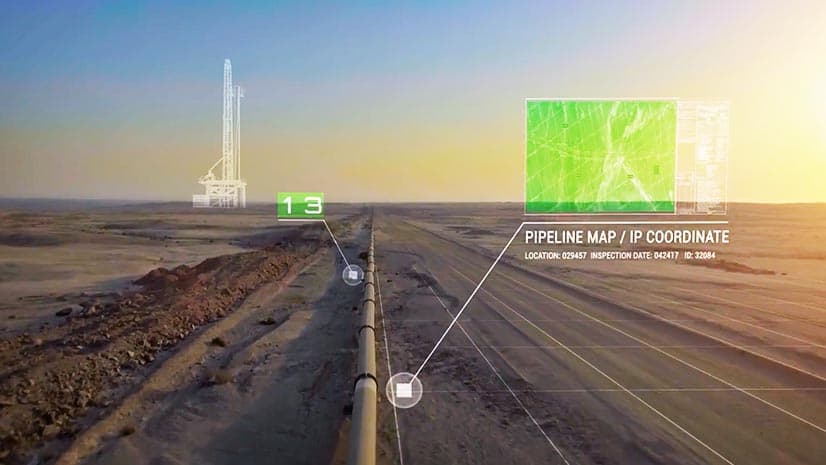

Major oil and gas firms used location analysis to decide where to develop projects and open new offices. In the wake of disasters like an oil spill, GIS analysts studied maps to evaluate environmental harms and mitigate impacts.

Utilities also saw the software’s potential. They recorded locations of gas lines, switching stations, and water mains with GIS, and ensured compliance with regulations. Telecommunications firms tracked antennas, roads, and depots.

By the mid-80s, universities had become GIS brain trusts, graduating students with expertise in spatial analysis. Those graduates became the new generation of business analysts, bringing location insights to the Fortune 500.

At this point, GIS was used largely by specialist teams and departments, but the seeds of its future as an enterprise technology had been planted.

The 1990s: The Geography of Customers and Networks

The strength of GIS has always been its ability to illustrate and analyze information tied to a place. When computing capabilities advanced significantly in the 1990s, GIS tools took their own leap forward.

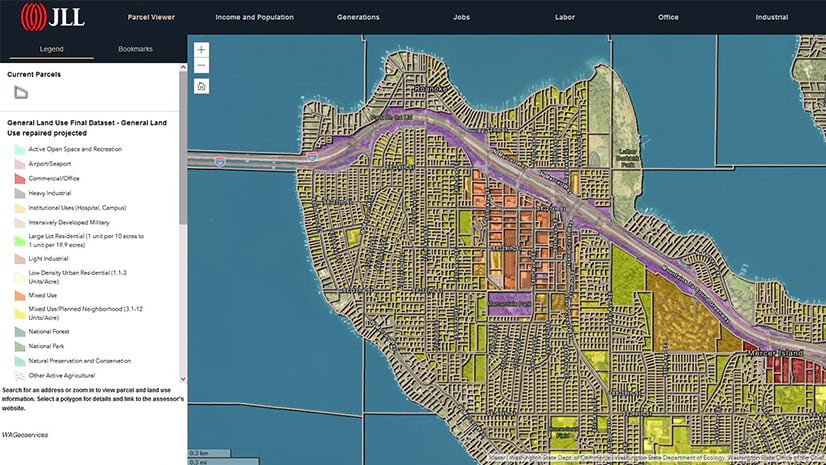

GIS became an engine of market analysis. Businesses used the technology to map stores and establish trade areas. Once they’d established an operational basemap, analysts identified demographic characteristics like age, income, and occupation that corresponded with strong sales performance.

In the supply chain, logistics, trucking, and delivery companies caught on to the power of location intelligence. By mapping warehouses and distribution centers in relation to homes and businesses, department stores, manufacturers, and service companies optimized routing and increased operational efficiency for deliveries and customer calls.

Some businesses began to use GIS to inform higher-level supply chain strategies. For example, when analyzing where to locate a new store, companies could identify areas best served by existing distribution centers and shipping routes.

Towards the end of the 1990s, construction and engineering firms discovered GIS as a source of truth for major infrastructure projects, tracking everything from requests for information (RFIs) to project schedules and deliverables. It was a sign of the new applications businesses were envisioning for location technology.

The 2000s: The Dawn of an Enterprise Technology

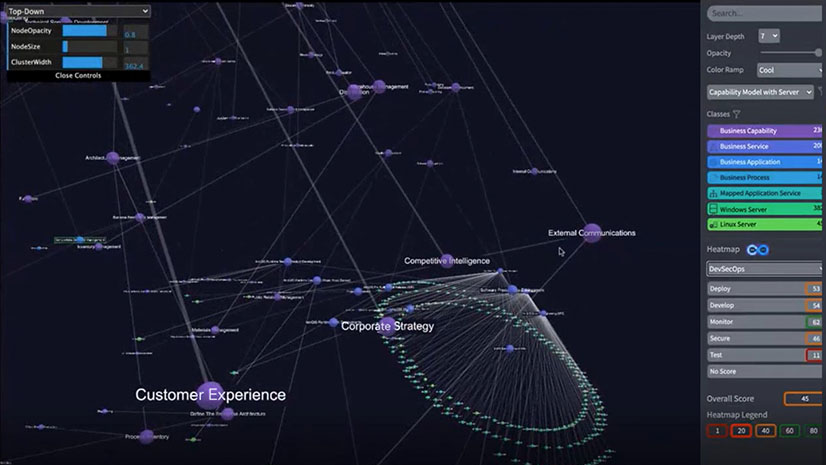

As the ‘90s came to a close, GIS was emerging from its role as the tool of technical teams, and its business applications continued to expand. By the 2000s, GIS was being used to predict sales, visualize market penetration, gather competitive intelligence, and create business continuity plans.

Companies began applying a location lens not only to business operations but to the labor force as well. Analysis of workforce availability informed hiring efforts and helped companies understand employee commutes.

Insurers, reinsurers, and other financial institutions turned to GIS for a more sophisticated understanding of risk. Companies found they could use location intelligence to adjust policies at the street level rather than by general zip codes.

As paper-based processes gave way to a digital future, location technology became a way to centralize and update blueprints, customer records, and other information. In one case in the early 2000s, a UK water utility used GIS to update 14,500 paper maps, bringing location data into the heart of the enterprise.

The 2010s: Location Intelligence Across the Enterprise

With digitization accelerating through the 2010s, a pattern emerged in many companies. GIS would start in the real estate department or a technical specialty. Colleagues from other business units would notice the dashboards and smart maps created by GIS analysts and ask for help developing their own GIS tools.

Soon, the original department would begin operating as a center of excellence, helping seed location intelligence throughout the organization, from the C-suite to field operations.

The enterprise approach was accelerated by cloud computing, which enabled more efficient collaboration across the company and outside the four walls with business partners. At the same time, advances in mobile technology gave GIS a stronger role in field operations, as service workers, real estate scouts, and other professionals used location intelligence to get more done, more efficiently, outside the office.

In the 2010s, imagery became a frequent input to GIS analysis. With aerial, satellite, or drone imagery, hedge funds assessed parking lot volumes to predict quarterly earnings. Construction and engineering firms tracked the progress of infrastructure projects through digital twins. Power companies used early advances in GeoAI to predict where they should trim potentially dangerous vegetation.

As the reality of climate risk sunk in, business leaders looked to GIS to track metrics like carbon emissions and weather risks across their portfolios. Another form of AI-based modeling helped companies predict short-term and long-term climate threats.

The Future of GIS in the Enterprise

In every decade, GIS has evolved to address the challenges of a complex business world, and today’s advances are no exception.

For firms at the forefront of AI, an understanding of location is essential to protecting data centers from extreme weather and accessing the huge supplies of energy needed to power AI algorithms. For companies answering regulatory calls to account for their impact on nature, GIS is driving new tools for measuring biodiversity data, emissions, and more.

As Tomlinson realized over 60 years ago, organizations focused on planning the future first need to ascertain where they stand today. Across the business community, GIS is the enterprise technology helping them do just that.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

July 14, 2025 |