Erik Henderson remembers the first time he held a portable GPS. It was 20 years ago, and the device wasn’t all that portable, weighing almost 35 pounds and crammed into a backpack with two impressive antennas sticking out of the top.

Back then, the technology that fits inside today’s average cell phone looked like something out of a science-fiction movie. Henderson’s job was to lug the gear through a hot, humid Florida summer, several days a week. He trudged across Jacksonville, collecting the location of storm-water lines and maintenance hole covers. A colleague in the office incorporated that data into a geographic information system (GIS) to create a citywide map of public works.

It was sweaty and, some might say, monotonous and underappreciated work. But from Henderson’s point of view as a summer intern, it was science come to life—a backpacking adventure that changed his future.

“I looked like a Ghostbuster!” recalls Henderson, who is now technical director of enterprise GIS at freight-rail giant CSX. “It was thrilling. I couldn’t believe that global positioning satellites were watching me walk around and that I was helping create storm-drain maps that were updated every week and printed on paper. It might not seem like much now, but I was hooked.”

That was 1999. Since then, the field of location intelligence has advanced dramatically.

Foreshadowing Drones, IoT, and GIS

In fact, Henderson doubts that 20 years ago he could have imagined how he and his team at CSX would use technology today. Now, they have created an app that uses real-time awareness from drones, GIS, and the IoT to help CSX immediately assess storm damage and speed recovery while protecting workers.

And he certainly could not have imagined accomplishing that in about four days while a hurricane bore down on the company’s rail network in North Carolina. But that’s what his team did in September 2018, in a whirlwind week that changed the way CSX looks at location intelligence. The company now sees the power of drones to save money and time—and deliver on customer expectations.

“Our GIS team played an important part in the recovery efforts in the aftermath of Hurricane Florence,” says Ricky Johnson, vice president of engineering for CSX. “Erik played an instrumental role, as he led his team to work quickly and safely while helping employees and infrastructure get back up and running.”

Ex-Ghostbuster Becomes Tech Disrupter

With powerful Hurricane Florence just days away from smashing into North Carolina, CSX braced for damage and searched for ways to speed up recovery efforts.

Asked by concerned company leaders how GIS could contribute to the storm response, Henderson was ready. He said his team could create a way to assess damage even while remnants of the storm still swirled, even if tracks were blocked with trees and bridges were washed out. What Henderson proposed—boots on the ground, drones in the air, and photos and videos transmitted to the hurricane-response room in Jacksonville—was brand-new for CSX.

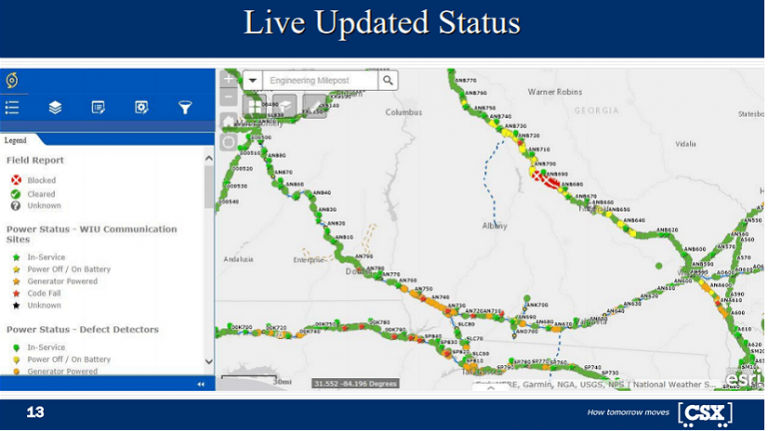

As if that wasn’t enough of a challenge, he also said they could produce an app with a shareable, interactive GIS map with layers of rich data, including aerial images, power outages, and rail networks. And he said they could build the app in a matter of days, before the storm hit the US coast.

If it worked, managers in the hurricane-operations room would see the real-time situation on the ground. In the past they’d prepared a response strategy by listening to reports on a speakerphone while jotting notes on paper maps and then reviewing spreadsheets of damaged assets.

It would be a dramatic technological leap.

“Until then, we mainly used GIS for asset management,” Henderson says. “We tracked railroad switches. We tracked signals on the ground and surveyed them when they moved.” Now, they would graduate to real-time situational awareness, using the IoT and drones to update GIS smart maps.

Speed of recovery is crucial to CSX because its business depends on safe, functioning railroad tracks to haul customer shipments. If the GIS team succeeded, it would change how the company responded to weather events along its 21,000 miles of lines, which go through 23 states, the District of Columbia, and 2 provinces of Canada.

Henderson’s supervisor listened to the plan, considered the upside and risks, and gave it his blessing.

With the impending storm packing winds of 130 miles per hour, the team would have little time to innovate and no time to field test. Still, Henderson was confident in the technology’s ability to provide real-time awareness and help CSX’s operations recover. And he knew he’d arrived at the moment in his career to lead that effort—although it had hardly been a straight-line journey.

A Map That Saved a Life and Shaped a Career

After Henderson and his wife graduated from Florida’s Jacksonville University (JU), they headed to their hometown of Boston to reunite with friends and family.

While working for the town of Natick, Massachusetts, in 2002, Henderson had the task of taking recent aerial images of the town and digitally layering them into GIS. When the police chief heard about the project, he asked for copies of the new maps showing the town’s structures, topography, and roads.

Not long after that, an Alzheimer’s patient wandered away from a senior center and into the surrounding woodlands. The police chief started poring over the aerial imagery in the new maps. With that location intelligence, he quickly identified all roads that dead-ended in the woods, and he sent police to each location.

One officer found the lost man sunk up to his waist in a marshy area. Stressed and confused, the senior citizen would not have lasted long out there. Henderson was amazed to hear the police chief on the news, praising the GIS maps that helped him pinpoint where to send his officers. “It was an absolute career-type moment to have the police chief say that the map you made helped save somebody,” he recalls.

The episode motivated Henderson to make location intelligence technology better known. “God forbid the town that doesn’t have similar maps, or the person who doesn’t have access, and something tragic happens because the right information wasn’t in the right person’s hands,” he says. “That’s what drives me.”

Professor Recalls Energy and Drive

His attitude does not surprise Ray Oldakowski. He was Henderson’s geography professor and mentor at JU, and later became a colleague after Henderson returned to Jacksonville to work for CSX.

Oldakowski remembers Henderson working at a restaurant bar and installing above-ground pools while going to school. “He’s always been very ambitious,” the professor says. “He makes opportunities for himself. He tries to show innovative ways to use the technology in the company, as opposed to being just a map servant, where people say, Make me a map of this or Make me a map of that.”

Henderson is even introducing location intelligence to today’s students. Oldakowski describes how he and Henderson have taught visiting high school students at JU. “Erik would talk to them about how to use GIS in the railroad industry. And then I’d talk a little bit about spatial analysis in general. And then they’d go out and get to fly the drone.”

Oldakowski praises his former student’s “dedication to people who have helped him,” saying, “He goes far above and beyond what almost any alumnus would do for a university.”

Innovating on Deadline as Hurricane Florence Approaches

Traveling from Jacksonville to the coast of the Carolinas, trying to meet an inflexible and fast-approaching deadline, Henderson and his CSX teammates found themselves tweaking the new GIS app even as they rode into the outer bands of Hurricane Florence.

What they planned was so new that the company’s repair crews, chainsaw teams, and other personnel deployed on the ground looked at them like they were unwelcome tourists. It didn’t help when Henderson explained just exactly what his team would be doing while the crews were hauling trees off tracks and cutting up downed wood.

“Well, we’re supposed to follow you and take pictures,” Henderson says he told the crews, recalling how unhelpful that sounded. “I’m standing there in front of these people who are holding chainsaws, and I’m holding a little toy drone like the ones some of them bought their kids for Christmas.”

But it didn’t take long for the new team to hit its stride. As the crews sloshed across muddy, sometimes flooded ground, picking their way around downed trees and dangerous washouts that left stretches of track dangling in the air, Henderson’s group launched a drone.

It sent back clear images of the tracks ahead so executives and decision-makers in the hurricane room in Jacksonville could begin their assessment.

“Their drones enabled us capture footage of damaged areas of our network faster,” says Johnson, the engineering vice president. “We were able to assess damage and deploy resources without having employees in unsafe environments or wasting precious time.”

Get the Drone Team!

Before long, the chainsaw gangs and the heavy machinery operators saw the benefit, too.

Henderson and his team used cameras mounted on drones to show ground crews what obstacles lay farther down the line. When the drones spotted enormous downed trees, supervisors sent the chainsaw crews elsewhere and called in cranes and bulldozers. This saved many hours, allowed managers to deploy crews effectively, and sped up the process of clearing thousands of trees and repairing bridges and tracks.

After a day or two, the crews started saying, “Somebody get the drone guys. I’m not going out on the track without the drone guys.”

Inside the Hurricane Operations Room

As the drone images reached headquarters in Jacksonville, the effect was immediate and electric.

The first interactive map wowed the decision-makers gathered in the hurricane-response room. When they asked for locations and conditions of various assets, or the status of communications networks and the power grid, the GIS team layered that data into smart maps and added color codes to note the status of each area.

When the Jacksonville group wanted to assess damage at a bridge in a flooded area of North Carolina, Henderson’s drone did the job safely and well. The image showed a major washout with such precision that managers were able to estimate the amount of gravel and fill needed to stabilize the area by counting the railroad ties in the image and adding up the distance across the affected area.

The real-time insight proved to be so valuable that the company changed its procedures. Now, a drone team and interactive smart maps are standard components of emergency management. Engineers and managers from other departments started asking for the app too, so Henderson’s team expanded training to include more employees.

When it became clear that police departments and first responders could use the GIS maps to coordinate their emergency responses, CSX found a way to share what has become a vital resource without putting any proprietary data at risk.

The Next Step Down the GIS Path

After almost two decades of work, Henderson believes even more strongly that GIS—and the location intelligence it generates—can be vital for many organizations.

“Leveraging technology to improve safety, operations, and reliability for our customers underpins everything that we do at CSX. My goal is to get everybody to benefit from it and to make this so readily accessible to people that they truly feel it’s easy to use,” he says. “Because access to real-time information is critical. It saves money, it saves lives, it saves time. And I’ve seen all that happen.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

March 18, 2025 |

May 28, 2025 |