Consumers are beginning to avoid products that aren’t made through sustainable practices, and legislators worldwide are converting those preferences into regulations. In response, businesses have invested in supply chain transparency. Knowing the source—and conditions at the source—of every product component can be cumbersome. However, it has become a business necessity, given procurement standards such as Norway’s new law barring government contracts for products that contribute to rain forest destruction.

Prominent multinationals such as Mondelēz, Procter & Gamble, and Cargill have vowed that they won’t source products connected to deforestation. Now a new form of location intelligence is helping these and other companies honor regulations and keep promises to consumers.

The Surprising Ubiquity of a Tropical Tree

The most widely used vegetable oil on the planet, palm oil is big business. Its production accounts for nearly 10 percent of the world’s permanent cropland. The oil plays a major role across the global economy—as an ingredient in shampoo, lipstick, ice cream, biofuels, and other consumer staples.

As a global refiner of palm oil, Bunge Loders Croklaan (BLC) closely monitors its supply chain. The commodity has been implicated in deforestation, giving rise to protests about harmful practices. To guard its reputation as a responsible palm oil source, BLC takes great care in selecting suppliers.

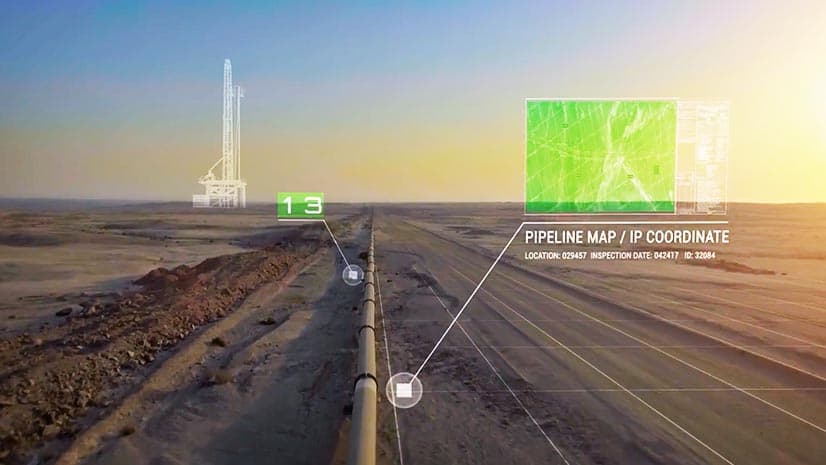

Lately, BLC has been purchasing and analyzing satellite imagery of supplier plantations to gain added assurances. Imagery can reveal whether suppliers are contributing to deforestation.

“We are mapping and monitoring our palm supply chain” says Tijs Lips, sustainability manager at BLC. “At the moment, we monitor all of our Malaysia supply base [20 million hectares] and soon we’ll add Indonesia, together covering our largest sourcing area.”

If BLC staff see any deforestation in the imagery, they mobilize quickly. “We look most closely at a two-kilometer-wide boundary outside the fence,” Lips explains. “If we see any encroachment, we gather information or send a team to gather intelligence to see if we need to take corrective measures.”

Location Technology Illuminates the Supply Chain

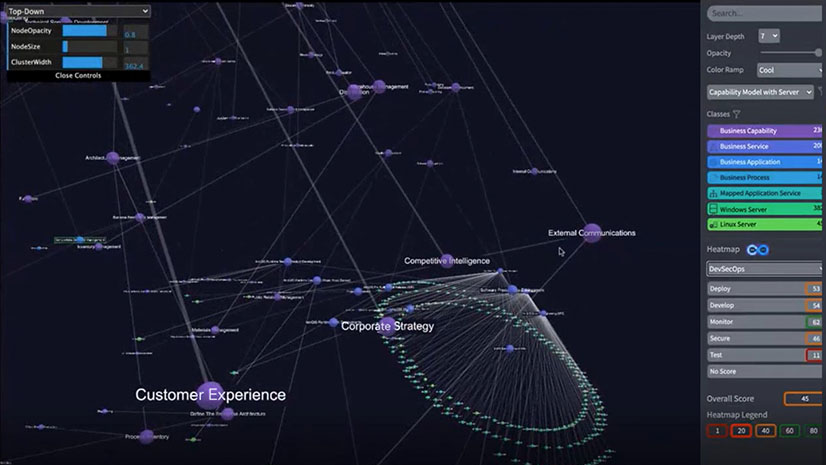

With offices in more than 23 countries and processing and manufacturing facilities in 60 locations around the world, BLC uses a geographic information system (GIS) to monitor the movement of palm oil through its supply network and to inform and prioritize action against unsustainable practices.

Through its GIS-based monitoring, the company can trace all its palm oil back to the mill where it was processed. BLC is working to have traceability to all plantations of origin as well.

“We have key performance indicators (KPIs) that we publish every quarter on dashboards, informed in part by our GIS efforts,” Lips says. “Some of the metrics we present include the amount of our area that we monitor, how much of our supply chain we have mapped, and how much we know about our supply.”

Certification Adds Oversight

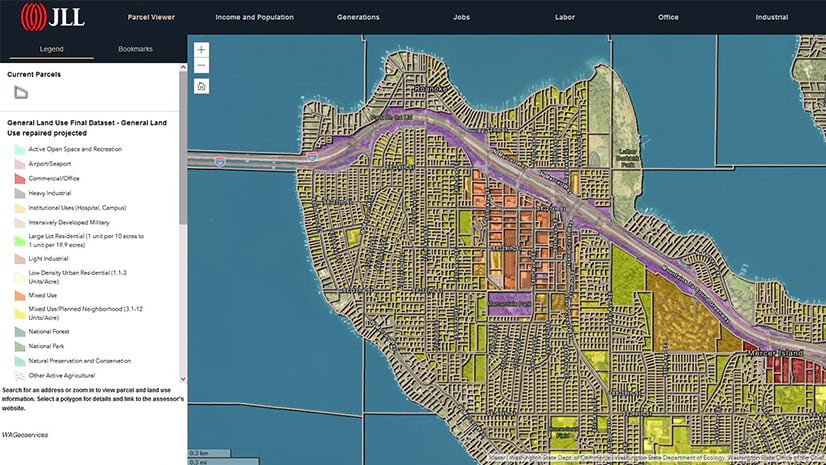

Part of the supply chain is certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which sets social and environmental criteria companies must meet to be certified as sustainable. RSPO monitors the company’s plantations and processing mills, and certified BLC suppliers command higher prices.

To support its own and others’ monitoring efforts, BLC works with the World Resources Institute (WRI), which has partnered with RSPO to set up an interactive mapping platform to monitor plantation compliance around the world. For BLC, this visibility means faster time to insight, which fosters quicker, better business decisions and more-sustainable practices.

Machine Learning Augments Location Intelligence

Demands for even faster location intelligence are driving BLC to automate its satellite imagery analysis. It’s one of a cohort of companies using artificial intelligence in the form of machine learning to stop harmful practices before they cause excessive damage.

Having the data on demand in a secured cloud environment allows BLC to uncover important relationships among the visual clues. The more queries and analysis BLC performs on the imagery, the better the model can predict potential problem areas.

Many researchers are tackling the prediction problem, looking at such things as an area’s proximity to roads, the distance between plantations, and the hilliness of the terrain against market factors to determine whether a forest is likely to be cut. Through this AI-based approach, BLC hopes to reduce the need for on-the-ground trips by investigators. Ultimately, it aims to predict deforestation.

The Business Impact of Keeping Watch

While the predictive capability matures, daily monitoring of palm oil producers remains a must.

“In order to have more impact, we need to support the industry in adopting more sustainable practices,” Lips says. “I believe our monitoring will help us to make the right sourcing and intervention decisions.”

Turning an industry to sustainable forest practices involves a combination of monitoring, auditing, reporting, and modifying behavior through training and incentives.

“Having a monitoring program in place goes a long way toward reducing risk and preempting any bad actions taken by individual farmers,” he says. “GIS-based monitoring—and the location intelligence it produces—can also provide a valuable resource for farmers, helping with insights that make operations more efficient.”

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

July 29, 2025 |

August 5, 2025 | Multiple Authors |