Cautious and precise in his role as information technology (IT) director of a municipal utility, Len Bundra doesn’t seem like the type to follow an unconventional career path through 23 cities in 12 states to the leading edge of innovation in geographic information system (GIS) technology.

But those who know Bundra say that being a meticulous techie is merely one side of the man who expected to become a factory worker or steelworker like most of his family. Instead, Bundra pursued an unorthodox career path to become an expert in location technology.

Part of his unpredictable journey might not be so surprising, since he was an early computer geek in the 1980s. “I always had a computer in my room, or two or three or four,” Bundra says. The names are still fresh in his mind: the VIC-20, the Commodore 64s, the Tandy, the IBM, the Apple IIe. “Oh, I forgot about the Sinclair,” he adds. “The point is, I had all these computers before I even left high school.”

That interest would help lead him down a zigzagging but ultimately rewarding professional path.

Hard Work Meets Happy Coincidence

Much of Bundra’s early career seemed driven by a mix of hard work, thirst for knowledge, and fortunate accidents. “My first job out of college in 1994 was in GIS, but I didn’t even know what those letters stood for,” he says.

And good thing he didn’t. If he had known he was taking a job to build a location-based intelligence system that helps companies plan strategy, see new trends, and increase efficiency and profit, he might have concluded he wasn’t qualified, decided not to apply for the job, and missed out on a satisfying career. But ignorance being bliss, he jumped into a high-pressure project and thrived.

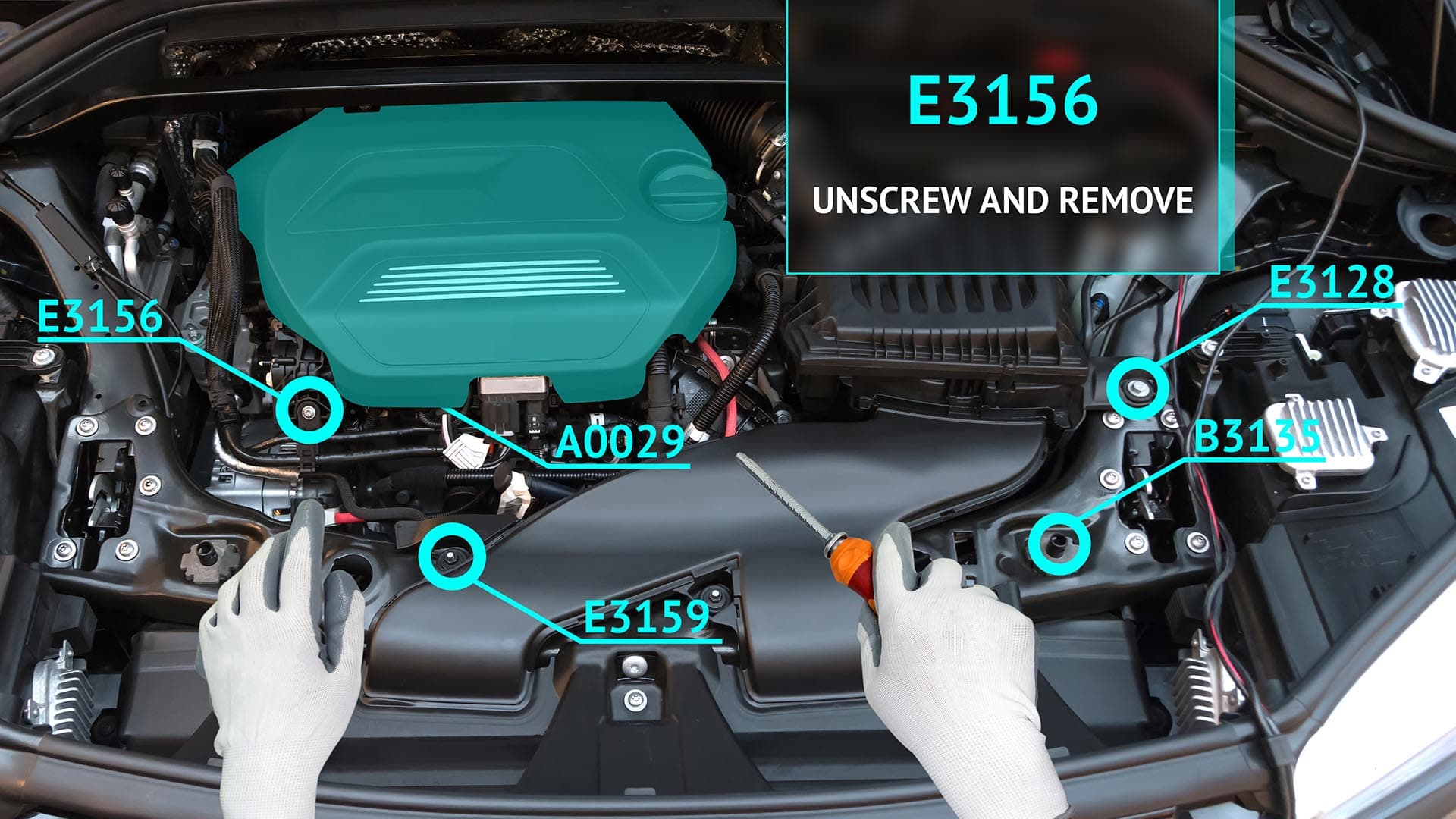

During his 25-year career, Bundra has built or improved location technology in dozens of places. He even found time to dream of new possibilities like a first-of-its-kind, augmented reality application that lets workers “see” underground utility lines through streets and dirt without digging. It drew interest from around the world. (Scroll down for a video demo.)

But all that seemed a long way off in 1994 when—equipped with an associate degree in computer-aided design from Lincoln Technical Institute and blocked from the steel industry by layoffs and shutdowns back home in Allentown, Pennsylvania—Bundra entered the workforce.

Learning Location Intelligence the Hard Way

Over the decades, GIS has evolved into a user-friendly, dashboard-ready tool that allows executives and line-of-business managers to track trends in their business and the economy. Yet despite a simple interface, the technology employs complex science—including artificial intelligence (AI), predictive modeling, and pattern detection algorithms—that fascinates devoted computer nerds and digital innovators.

When Bundra landed his first job, the one that inadvertently set him on a GIS pathway, the technology wasn’t easily managed by nonexperts. He showed up with 25 other new hires—all young programmers—at a big engineering company in Philadelphia, with one thing in common.

“None of us had ever heard the word GIS,” Bundra says. “But we all knew how to program, and we all knew we had to figure out what GIS was and how to build one for the City of Omaha 1,200 miles away—because that’s what the contract called for.”

So Bundra did what any young, obsessed programmer would do: he logged 100-hour workweeks, learned new programs on the fly, slept at the office, and kept pushing.

“It was like basic training for your future in GIS. And who would have known I had one? I didn’t ask for that. But it’s what I needed.”

The high-pressure atmosphere was intellectually stimulating. “There was no environment where I had to learn more quickly under more pressure and put it into effect immediately. For two years, we were basically all locked in the same room, pulling our hair out. And I’m grateful for that experience.”

The group ultimately succeeded in building a GIS from scratch. Bundra was elated. As he came to understand the power of location technology to reveal connections between objects, events, actions, and outcomes, he was more than intrigued. “I was hooked.”

He next tried working with the software at other engineering firms. But he was eager to learn all facets of his new craft and wasn’t sure any single job would fit him at the time. “I was still single, young, full of energy.”

Rather than seek a full-time job, he decided to create his own.

A Particular Set of Skills

The Bundra business plan was simple: build a network of engineering companies and keep an ear out for news of GIS contracts.

When he heard possibilities, he’d approach a firm with this pitch:

“Here’s my skill set. Here’s what I’m going to come in and do. I’m going to sign a four-month contract with you for this amount. You don’t have to give me an office and say, ‘We see a bright future with you here.’ When I’m done, you’ll have your GIS and you won’t have to figure out what to do with me. I’ll leave and move on to my next contract.”

It worked. “I did that 23 times,” Bundra says. “I paid rent in 23 cities in 12 states during my time as a consultant. You rent a house on a month-to-month lease, and while you’re building this system, you’re getting ready to leave for the next job. That’s how I lived for 12 years.”

From Philadelphia to Denver to West Palm Beach and beyond, Bundra improved existing GIS technology or built it from scratch.

“I just had a burning desire to do cool stuff with computers and math. I think I was really enthralled by the technology and wanted to be a part of what was happening.”

Building a Keen Business Sense

Just like his early boot camp in location technology, Bundra’s travels from state to state taught him skills he didn’t know he’d need later on.

It forced him to develop his business side: how to negotiate, sense client needs, be alert to cultural differences in private and public sectors, and pay attention to the inner dynamics of an organization.

It also made him aware of information silos lurking behind departmental barriers and the need to break them down to create true location intelligence across an organization. But he did not come on the scene as a corporate disrupter; he arrived as a freelancer on a limited contract. Those who might have otherwise hesitated to share data didn’t see him as an internal competitor, just a short-term inconvenience. So if he asked for data from various departments to build a location-based system, he usually got what he needed.

Bundra did his work and moved on. But he also noticed that as GIS grew in importance to the business, the gulf between IT and GIS departments grew harder to navigate, as some traditional IT managers were reluctant to share the data they maintained throughout a company.

It was an issue he always kept in mind.

From Paper Maps in a Drawer to GIS in the Cloud

In 2004, after years of chasing short-term work as an independent contractor for engineering firms, Bundra decided to change his strategy. Instead of offering his services to large engineering firms as a subcontractor, he bid directly on a contract at a municipal utility in New Jersey.

The Toms River Municipal Utilities Authority (TRMUA) was looking for someone to build its GIS. The engagement would be more complicated than Bundra’s typical four-month gigs. And he wasn’t really sure he could do the job by himself, even with help from TRMUA employees. Only after winning the contract did he fully appreciate the magnitude of the challenge.

For decades, the utility had been relying on paper maps to find pipes, mains, and manhole covers. Time, energy, and money were wasted searching for the right files in the office and the right pipelines in the ground.

“We were in the stone age,” says Michael Tesch, TRMUA’s pump stations foreman. “We didn’t know about GIS until Len came in. The front office was literally cutting with scissors and taping new changes onto the large tax map, which was on a giant table.”

Of course, it was impossible to take that huge map into the field, and it didn’t hold all the information needed by utility workers, anyway.

“We’d go out to try to find a leak, and if we thought we found the right spot, we still wouldn’t know the direction the pipe flowed,” Tesch says. “There were places where we didn’t know where the manholes were for the mains. If guys were there for 20 years, they knew it. But nobody else did.”

From Stone Age to Digital Age

Creating a system of location intelligence for Toms River involved digitizing 40 years of maps and files, checking coordinates on 9,600 utility hole covers, and entering 600,000 pipeline and utility hole details into a central database.

With no digitized information, there was no IT director at the time, which was fine by Bundra, who essentially filled that role. In turn, that meant fewer information silos and bureaucratic headaches.

After two years of work, the GIS was ready. It was a welcome relief. Now, if there was a leak somewhere in the township, there was no need to drive to the office to see what files could be found. The info was accessible remotely by computer. The employees were thrilled with the modernization, but Bundra saw the need to keep adding layers of information to the system.

“He even added a layer for trouble spots where sewer pipes tended to back up,” says Michael Sica, rehabilitation foreman. “He has a layer that is color coded, meaning it has to be checked maybe once a year.”

TRMUA engineer Nicholas Otten finds the continual updating and user-friendly maps very helpful. “I really appreciate that it’s a one-stop shopping database. It lets me see the whole picture of the system at my desk. That includes attributes of all the pipes, their installation year, their material, when they may have been rehabbed. I can even click on a pipe to see a report of flow rate and the latest video inspection inside the pipe.”

It's sort of nice to be the guy that has an idea for an app, and the decision isn't contentious. It usually only lasts 15 minutes, and it doesn't involve a conference room or a premeeting to discuss the meeting to discuss the preschedule.

Coming off the Road

After building the system, Bundra was thinking about his next move when the Toms River authority asked him to stay on as director of GIS and IT.

It would be the first time he worked as a full-time employee, but he was ready to get off the road and settle down. It allowed him to get married, build stable friendships, and start raising a family.

The challenge and stability of his new job even stimulated him to think about innovations such as the augmented reality goggles that let workers see the underground utility pipes as they walk down a street. After thinking it through for several years and partnering with another group, he helped develop a prototype system in 2017 that saves time and money, and increases safety in the field.

Coworkers appreciate Bundra’s efforts and his intense drive for precision. But they nearly all describe him by his office demeanor—the man who sees the world digitally, all those zeros and ones just waiting to be filed in the data banks.

A Multifaceted Man

Tesch, however, knows there’s another side to the GIS director. He and his wife often go out with Bundra and his wife. Over the years, the two utility workers have been into motorcycles, surf fishing, and skydiving. The button-down, cautious Bundra even celebrated one New Year’s Eve with a nighttime skydive over Florida.

Most people at work have no idea, Tesch says. “No, you would never know it. He seems like the poster boy for computer guys, not a motorcycle-riding skydiver. He’s definitely both. There’s a dichotomy with Len. He’s all business with the computers; but outside of work, he’s jumping out of planes.”

Not bad for a guy who once wondered if his chance for professional success and a fulfilling personal life would disappear with the closing of the steel mills and factories around his hometown—a guy who didn’t know what GIS stood for until it was his job to build one back in 1994.

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

November 12, 2018 |

July 25, 2023 |

February 1, 2022 |

March 18, 2025 |

May 28, 2025 |