Bentonville had a people problem: They would come to work in the Northwest Arkansas city that is home to Walmart’s headquarters, but they would only stay until they could find employment somewhere more appealing.

“People would take the jobs for the résumé and the salary. And then after a few years of having both, they’d leave because Bentonville wasn’t the type of place that could keep them there,” says John Houseal, a Chicago consultant who works with the city on planning and development issues.

So, in 2005–6, the city gathered with Walmart officials and other major employers and civic leaders and decided they had to not only slow or stop the brain drain but actually reverse it if they wanted their tax base to grow and their community to thrive.

One of Bentonville’s first steps was devising a new comprehensive plan using location intelligence powered by a modern geographic information system (GIS). The data-rich, mapping-based technology helped officials look at issues large and small, from details as minute as individual parcel designations all the way up to population projections for the region.

That plan gave them a baseline of what the city was and, more importantly, wanted to be. That was especially important in an environment where cities and suburbs large and small are fighting to attract and retain businesses and their workforces.

“We are a small city that is doing its dead level best to create an environment where it can recruit and retain top-notch talent, understanding fully that it really is a global competition for that talent now,” says Troy Galloway, Bentonville’s community and economic development director. “It used to be regional, then national, but it really has gone global.”

Growing the Right Amenities

Among those attracted to the evolving Bentonville was Rob Apple, managing director of the Ropeswing Hospitality Group, which today owns and operates restaurants, lounges, and meeting space downtown. Apple, a Northwest Arkansas native, had moved away from his home state, but returned to Bentonville to take a job with a consumer products company. Upon his return, he was reminded of how limited the social and culinary options were.

“There wasn’t much going on when we first moved to the downtown area,” Apple told WhereNext. “After a few years it became clear that the area was going to change, and we were fortunate enough to open a small restaurant in the middle of it all in 2011.”

The restaurant caught on, and Ropeswing has been growing ever since—and providing the kinds of establishments young professionals value. It now operates an artisanal cocktail bar and farm-to-table restaurants for foodies—a term many Millennials associate with—featuring local fare and gluten-free options.

“We have a long and growing list of concept ideas that we would like to explore. Some of our ideas in development are a result of a gap in the market,” Apple says. “Other concepts in development are bigger ideas that no one is necessarily asking for, but we hope they contribute in a meaningful way to our community. We are comfortable pursuing projects like this because the area has been so supportive of new ideas.”

Bentonville Redesigned Itself to Attract Business, Workforce

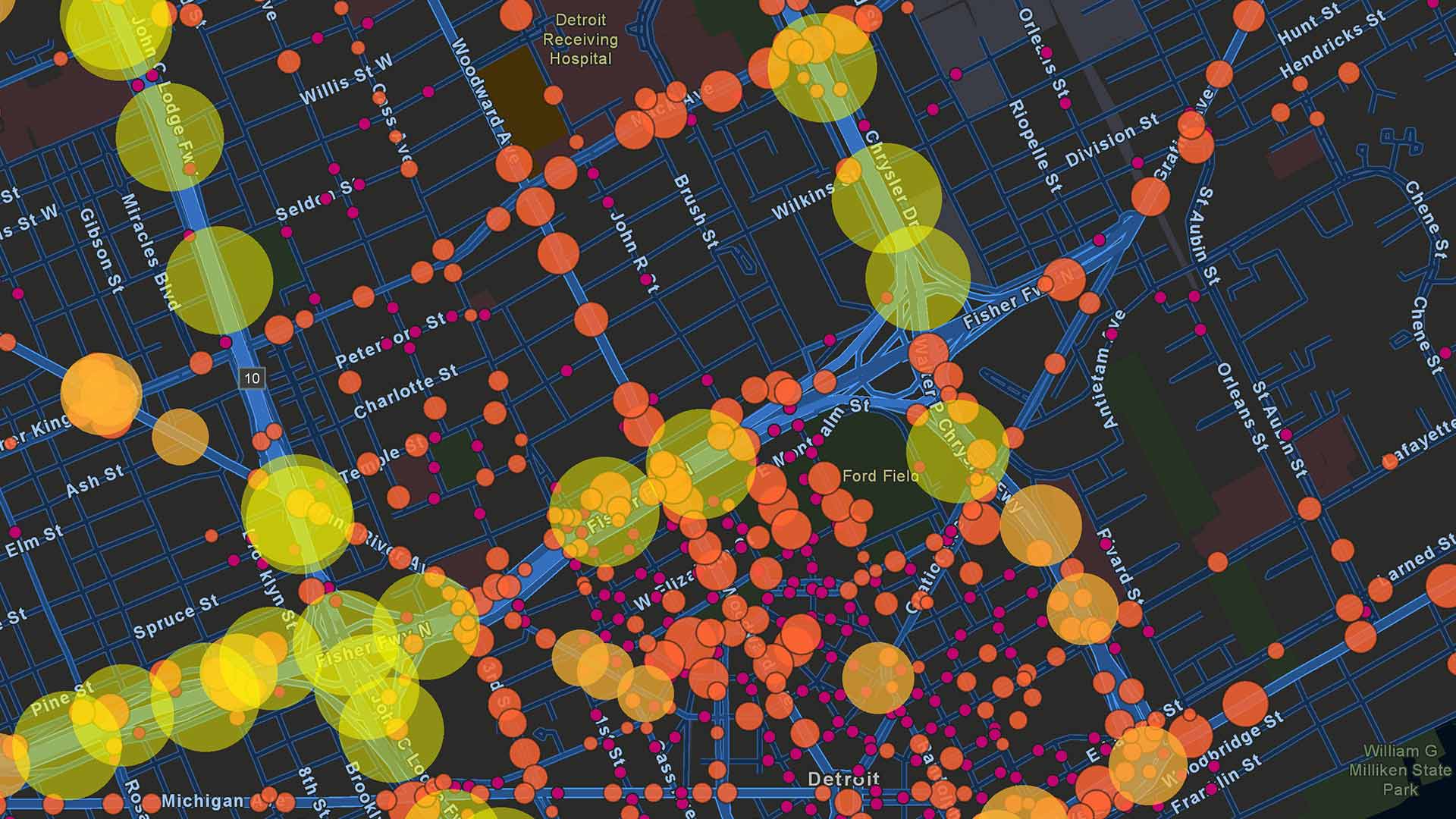

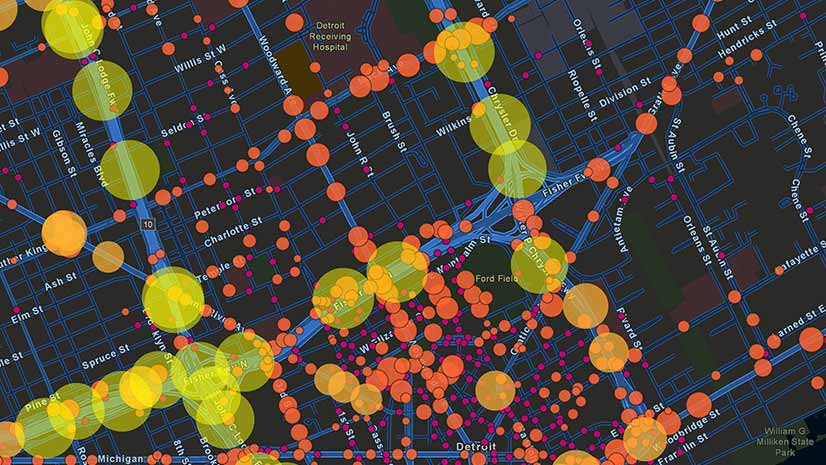

As the new Bentonville began emerging, the city and its main consulting team, Houseal Lavigne Associates of Chicago, took deeper dives into what amounted to a redesign of the city. They turned to sophisticated GIS tools to perform location analytics and set the stage for additional growth.

Their plans combined high-tech GIS applications with old-fashioned human intel gleaned from charettes with business owners, residents, and anyone with a stake in what goes on in Bentonville.

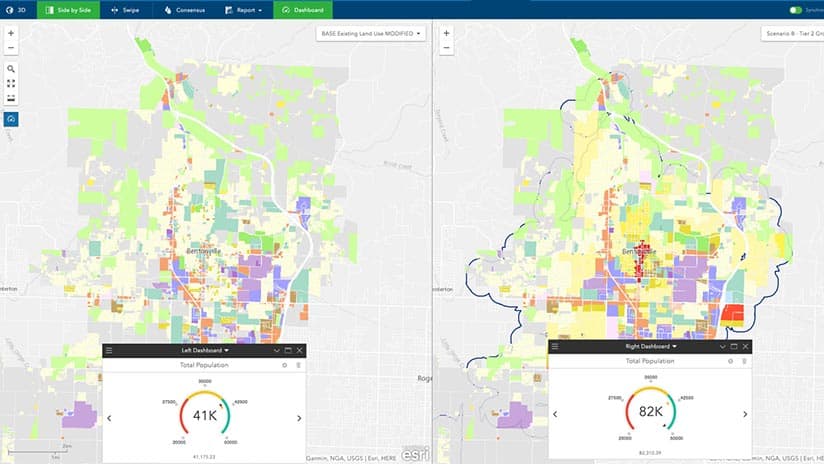

“The question,” Houseal says, “is can you analyze that data and then tell a story that people will pay attention to and take things away from?” Houseal, his partner Devin Lavigne, and city planners used a variety of GIS capabilities to tell that story and plot Bentonville’s course. For example, they used GIS-based maps and dashboards to test various development scenarios and their potential impacts on population (see image at left).

Another GIS tool allowed the team to draw a sketch plan that was laid over an aerial map to identify where street connections should occur and environmentally sensitive areas should be preserved and protected.

GIS also gave planners a deeper understanding of the city’s economics, helping them determine the average spending power of current and future residents, and calculating demographic trends that pinpointed gaps in the housing market.

All that data was important for businesses to consider while planning to branch out or move to Bentonville. It also informed city officials’ plans.

Lavigne says Bentonville, which has grown more than 300 percent since 1990, has to be careful that it expands in the right way. The planning capabilities of GIS, he says, helped planners “accommodate anticipated growth in a more responsible manner consistent with the community’s vision”—for instance, by visualizing how neighborhood growth will affect the city’s infrastructure, residential density, and access to downtown amenities.

Cities and the Millennial Workforce

Bentonville is hardly alone when it comes to upping its game.

Communities of all sizes are doing everything they can to become more competitive in attracting the young, educated, millennial workforce experts believe is a prerequisite to luring new businesses.

Places across the country are redesigning and rezoning roads, town squares, and entertainment districts to make them more bicycle and walker friendly. Such alterations can win over Millennials, who are not nearly as car-centric as their aging baby boomer parents. They’re also welcoming the kinds of establishments Ropeswing and Rob Apple are bringing to Bentonville.

Yes, tax breaks and free land remain important in wooing and retaining businesses and their accompanying workforces. Witness the incentive-laden deals cities are offering Amazon as the online giant eyes potential landing spots for a second headquarters.

But it’s all for naught if the brand name of a business can attract talent and the city where it’s located isn’t interesting enough to keep employees for more than a couple of years.

Amazon’s short list of 20 cities—ranging from behemoths such as New York City and Los Angeles to smaller metro areas like Nashville and Columbus, Ohio—offer a lot of the urban and suburban niceties today’s mobile workforce craves. That’s everything from funky coffee shops and local restaurants to microbreweries, ethnic food, walkable downtowns, and parks. Those characteristics just happen to be among the must-haves for people born between 1981 and 1996, according to a survey of 2,000 Millennials by the apartment-listing website Abodo.

We published a comprehensive plan in 2006 that pointed towards the downtown as the platform for growth and development. That set the stage for efforts to recruit businesses to downtown and work on the aesthetics of the downtown.

Competing to Offer What Young Workers Seek

For economic developers, the takeaway should be that no locale is off the map, provided it has what young workers seek.

More than ever, research indicates, Millennials are choosing their employer not so much by what the company does or the benefits it has to offer, but whether the community it calls home meets certain standards. In other words, it’s about lifestyles.

“A trend we’re seeing in competitiveness is positioning your community not financially but in terms of quality of life, through all these amenities. That’s the economic incentive that makes people want to work there and corporations want to locate there,” Houseal says.

A recent study of Millennials shows that people ranging in age from 22 to 37 are working and living in city centers over suburbs, in part because suburbs lack the lifestyle and social options they demand. Businesses are taking the hint and moving to city centers: GE to Boston, McDonald’s to Chicago, and Aetna to Manhattan—all places with a plethora of young workers. Smaller cities, such as Bentonville, are changing their lifestyle quotient to compete.

But as people move in, snapping up the best and most economical places to live, prices tend to rise, creating an affordable housing problem for growing communities. Bentonville has seen the price of downtown property soar to $200 a square foot, which can be out of the financial range of younger Millennials burdened with college loan debt.

“Some of our success is actually running contrary to what we originally were wanting to achieve, and that’s a place where people wanted to live,” Galloway says. “We’ve certainly done that, but now there’s a lot of people that can’t afford to live there.”

Bentonville’s population has risen steadily in recent years, from roughly 32,000 in 2006 to more than 47,000 today, US Census Bureau figures show. That’s an increase of almost 47 percent since the city put in place its original comprehensive plan to rebuild Bentonville and its downtown. Galloway expects the city’s population to hit 50,000 this year and grow as much as 50 percent more during the next decade and a half.

A 2020 Plan for Northwest Arkansas

Galloway says Bentonville will keep developing, and will use its planning capabilities and GIS technology to manage that growth.

The Walton Family Foundation, for example, is working on a 2020 plan that focuses on bringing more attainable housing, on-street cycling infrastructure, and mass transit to Bentonville and Northwest Arkansas.

One change almost certain to happen is altering the zoning laws to allow for more dense development in and around downtown. That should create an environment for the construction of less-expensive housing.

As they continue their planning efforts, officials are using ever-more intuitive technology, including a GIS application complete with a 3D digital library of the city’s growth areas. Houseal Lavigne recently integrated those GIS models into a virtual reality (VR) program that showcased different scenarios of future growth. Through the VR app, the planning team was “dropped” into a virtual scene to experience the proposed changes as they would in real life.

“Bentonville has to always be a place where people want to come, they want to live, they want to recreate, they want to spend their free time,” Galloway says. “And if we can achieve that, we will inevitably be able to attract the people, the demographics, the workforce that our community needs to be successful long term.”

Among the changes that have come to Bentonville since the 2005–6 plan took effect:

- The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened during late 2011. Funded by the Walton family, it exhibits world-class collections and anchors the city’s expanding cultural efforts.

- A series of bike paths and lanes were built throughout the city and surrounding area. The Razorback Greenway is one of the more prominent trails, running almost 30 miles, from north of Bentonville to the south edge of Fayetteville. A challenging and well-regarded network of mountain bike trails was opened, too.

- An entertainment district in and around the city square features trendy restaurants, shops, and lounges.

A Wager on Growth

Bentonville, according to a study released earlier this year, is leading a renaissance of sorts in Northwest Arkansas. Produced by University of Arkansas Center for Business and Economic Research and sponsored by the Walton Family Foundation, the report shows that from 2012 to 2017, downtown Bentonville had the largest population increase and issued the most building permits for commercial and residential units in the region.

A few years ago, Bentonville didn't have brew pubs and white table cloth restaurants and food trucks and movie theater festivals or arts festivals. They now have all of that.

Houseal sums up the Bentonville transformation this way: “A lot of it was fueled by the city as well as Walmart and the Walton Foundation and others. They really focused on what the young workforce wants—recreational amenities, outdoor amenities, cultural amenities, educational amenities, and restaurant amenities. The result is a better community, not just for millennials, but for everyone.”

Ropeswing is a case in point. Apple’s company now runs two popular restaurants, a lounge and event space, and has at least two projects in the planning stages for Bentonville. One notion coming to fruition, he says, is “The Holler,” which will feature shuffleboard courts—a growing pastime for Millennials—work areas with fiber internet, live music, a culinary bar, and a coffee program. The idea is to encourage everything from meeting for drinks and a bite to eat to starting a new business, Apple says. His target audience is all age groups, not just Millennials.

“In the Millennial category,” Apple says, “there are artists, young professionals, entrepreneurs, parents, and singles. I think this reality pushes us to focus on the fundamentals of good food and good design. We’re betting that everyone can get behind that.”

Bentonville is making a similar bet—tested and planned with the help of GIS-powered location intelligence—that the changes and improvements it has made and continue to make will appeal to a wide range of employees as well as employers. So far, it looks like a winning wager.

Images courtesy of Houseal Lavigne

The Esri Brief

Trending insights from WhereNext and other leading publicationsTrending articles

December 5, 2024 |

July 25, 2023 |

November 12, 2018 |

April 29, 2025 |

February 1, 2022 |

May 6, 2025 |