August 12, 2021

When a Hoopa Valley High School senior living on the Yurok Reservation in Northern California answered the door to US Census workers in March 2020, it was a moment years in the making.

Despite having the largest tribal membership in California, the Yurok Tribe—like many tribal nations—had been historically undercounted in the US Census. Hard-to-reach homes, out-of-date addresses, lack of internet access and cell service, and a long-standing reluctance among members to participate in state and federal government initiatives have all been contributing factors.

While the Yurok Tribe has recorded the enrollment of 6,311 members as recently as April, the US Census had estimated that just 836 people lived on the reservation.

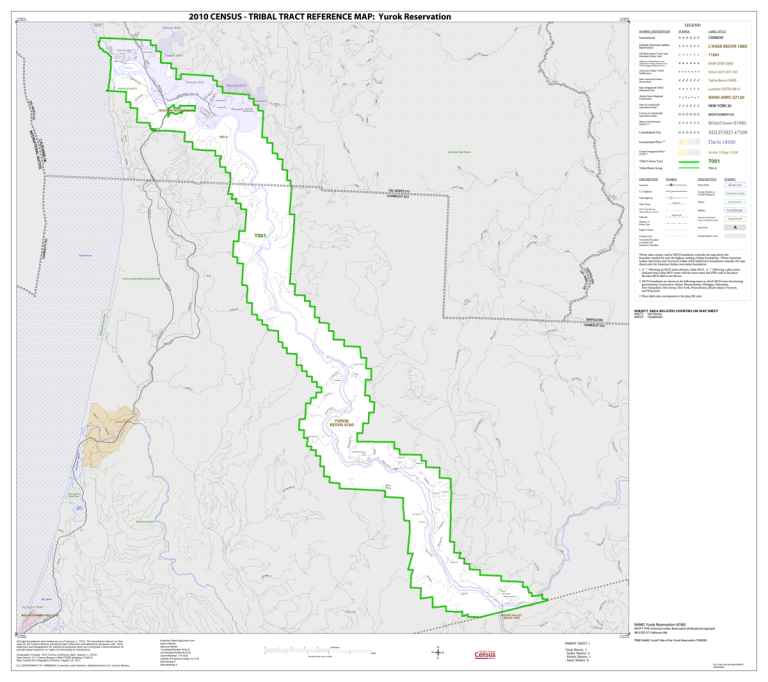

Because census counts determine the amount of eligible government relief offered to communities, the tribe set out to ensure that every member was counted. Two geographic information system (GIS) specialists worked hard to update addresses and create maps for census enumerators to help them reach everyone, no matter how remote.

“You can tell someone, ‘Hey, the driveway is by this mile marker,’ but it’s just not as good as having a map that you can follow,” said Shaonna Chase, who, along with Elaina O’Rourke, started the Yurok Complete Count Committee.

Every 10 years, the US Census Bureau attempts to count all the country’s residents—a massive undertaking with more than 331 million people living in nearly 123 million households. The 2020 Census marked the first time the survey could be completed online, but door-to-door counting is still needed to follow up with those who don’t reply. Many of those households are considered “hard to reach” due to their rural locations and the lack of modern infrastructure like paved roads. Accurate maps play a key role in the ability of census enumerators to count people.

The Yurok Tribe began efforts to ensure accurate representation of people and place over 15 years ago when O’Rourke created the GIS team. At the time, much of the upriver (near Weitchpec) part of the reservation (separated geographically from the lower part) lacked electricity and internet access and the homes had never been accurately mapped. “You need four wheel drive to get to some people’s houses,” O’Rourke said. “And we don’t have cell service in the upriver part of the reservation.”

In 2009, the Public Safety Department started mapping residences and assigning physical addresses to many of those properties, and in 2014, the GIS team completed the project. To do this, the team used data previously gathered by a local timber company using lidar technology, an optical remote-sensing technique that involves sending and receiving laser pulses from a sensor aboard an aircraft that reflect from objects and the ground to create a three-dimensional representation called a point cloud. The 3D mesh of points is then colored and filled in to identify landscape features. The foresters use lidar to inventory trees. The tribe used the data to map roads and buildings.

In 2018, when the team was given the geographic data used by the Census Bureau from the 2010 census, Chase was shocked by how inaccurate it was. “On their list for the upriver part of the reservation, every single one of those census addresses were inaccurate or they were out of place, they didn’t have the right road name, they didn’t have the correct number. I deleted every single one of them and put in all of ours,” Chase said.

The population and demographic data collected by the Census Bureau is used to distribute over $1.5 trillion in federal funds each year. Some of the funds go to building or maintaining infrastructure, such as roads and bridges. Many of the federally funded programs have a direct impact on the day to day lives of residents such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) health clinics and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Other programs include the provision of health clinics, low-income housing loans, and public housing. The amount of money allocated to these programs is based on the number of residents counted.

Historically low census participation is not just a Yurok Tribe phenomenon. In 2010, the Census Bureau reported that American Indians and Alaska Natives living on reservations were undercounted by 4.9 percent, which is more than twice the rate of other racial minorities. That translates to roughly $75.5 billion of federal assistance lost each year because of undercounting.

Racial misclassification has long been an issue among native populations. A 1997 American Journal of Public Health study found that at the time of death, about 75 percent of native people were racially misclassified.

Experts believe that mistrust of federal and state governments through generations is to blame for undercounting.

Chase and O’Rourke discovered that the best way to overcome it was to engage the community long before the count began. In 2019 and early 2020, the Yurok Complete Count Committee hosted five community events with a free dinner; census-themed games; presentation on census information; and raffle prizes of art, crafts, and jewelry created by local artists. The dinners were hosted at community centers with school or sports groups catering for the events as a fundraising activity. Turnout exceeded their expectations.

“We really put in the effort to keep things local and within our own community so that more people were apt to come and check out what we were doing,” O’Rourke explained. “We were able to talk people out of the whole ‘don’t trust the government’ belief because we explained what the numbers were for and what programs the funding was going to go to. We gave specific examples of what the census could do that mattered to our people.”

Chase and O’Rourke said the decision to have a high school senior be the first to fill out the 2020 Census on the reservation was also by design. The Yurok Tribal Council’s vice chairman Frankie Myers suggested aiming the first count outreach at young people because the 18–24-year-old age range has historically been the most undercounted.

“It was one of our hopes that the young people would talk to their family and their elders, and help their elders get counted,” O’Rourke said.

Thanks to their effort to accurately locate each house geographically on the reservation, and to engage the location intelligence of the community, the GIS team knew the 2020 Census was going to be different. “We’ve been building our data for the last 10 years. And because of that, Yurok had a 100 percent complete count for the first time.” O’Rourke said.