October 9, 2020

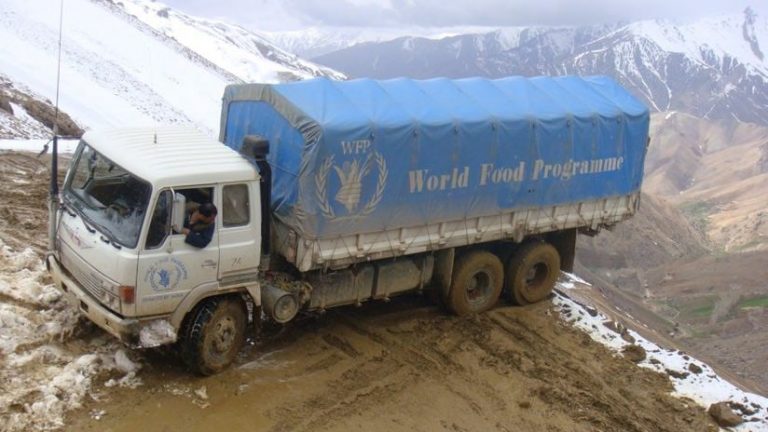

With its inaccessible mountainous areas and complex and protracted conflict, Afghanistan poses unique challenges for the World Food Programme as it works to achieve zero hunger. Climate change, disasters stemming from natural events, demographic shifts, and a limited road network continue to constrain development efforts.

Earthquakes, landslides and avalanches can block the few roads winding through the country’s rugged terrain. Two decades of armed conflict add a distinct security element to an already challenging environment. More recently, drought, floods and the COVID-19 pandemic have been driving more families into food insecurity across the country.

To navigate Afghanistan’s challenging operating environment, WFP teams have come to rely on evidence-based decision making, with mapping apps sharing on-the-ground data to support actions before they make a move.

“A major challenge for the delivery of assistance to the most vulnerable populations in remote areas is not only insecurity but also a lack of proper roads,” said Falaknaaz Khan, senior logistics associate at WFP’s Kabul Warehouse. “Most of these locations are inaccessible during winter. Soon after the snow begins to melt, it starts raining from April to May and sometimes until June. Muddy roads again result in the cancellation of missions or cause delays in deliveries.”

At the beginning of an operation, WFP teams use an online geographic information system (GIS) to assess vulnerability and determine how many people in the region need of food. Once the work is underway, they call up the same app that combines security, supply chain and programme layers to monitor what’s happening.

“I find it very useful to visualize different aspects of operations—from needs, road conditions, security context, and supply routes,” said Vladimir Jovcev, head of WFP’s supply chain in Afghanistan. “It allows us to better plan the deliveries, mitigate the risks in a very complex environment and ensure that food is received by the intended beneficiaries.”

This online mapping enables informed decision-making as key operational staff often discuss districts or locations that others can’t relate to. By visualizing the access or operational issues on a shared platform with layers for security, supply chain, vulnerability analysis and mapping or programmatic goals, stakeholders achieve a common understanding. It helps to break down silos and connect the dots.

The security layers provide an understanding of areas controlled by armed actors and conflict hot spots, which then enables operations and security staff to work on access strategies based on humanitarian negotiations and avoidance of conflict. WFP taps into its networks to prepare the ground for fleet and staff movement, as well as programmatic activity.

The Afghan government maintains control of Kabul, provincial capitals, major population centers, most district centers and the main supply routes, according to a June 2020 report from the US Department of Defense on security and stability. However, the current level of Taliban violence and attacks is the highest ever recorded. The Taliban is gradually eroding security structures and expanding its areas of control.

In May 2020, an attack against a maternity hospital in Kabul was traced to ISIS. This was its first attack since ISIS lost its stronghold in Nangarhar province in November 2019, further complicating a difficult operating environment.

These challenging security issues continue to impede the work of international humanitarian staff, who must navigate shifts in local and regional control to reach and serve people in need.

In line with the humanitarian principle of neutrality, WFP negotiates with all stakeholders. “We don’t limit ourselves to government-controlled areas as we have to reach all the people in need,” said Henry Chamberlain, head of security for WFP in Afghanistan. “We work with most Non-State Armed Groups (NSAG) that control territories and access.”

The combination of data and analysis has allowed WFP to pioneer a new global acceptance policy in which communities are not considered as passive recipients of aid, but are asked to provide security guarantees and become stakeholders in programme delivery. This data-driven approach determines who to engage and negotiate with to build relationships and gain acceptance of the aid before it’s delivered. This, in turn, has allowed WFP to move away from the conventional armed escorts approach, which relies on military force and deterrence and can cause humanitarian convoys to become a target for armed groups. This has lowered the risk of field missions and allowed WFP to deliver aid to areas that were too risky to supply in the past.

“For field missions into NSAG-controlled areas, we can now clearly understand the geographical limits of those missions, the conflict hot spots and priority areas,” Chamberlain said. “This allows us to formulate an engagement and communications plan for areas that are easier or that we must access. Viewing fleet truck routes provides incredible insight into where we have security and support. This has improved delivery in many areas and allowed us to avoid security incidents.”

In Afghanistan, WFP delivers food primarily by truck given the mercurial weather and steep terrain. When there’s a physical roadblock or a security access constraint, drivers on the ground can gather and report information about changing conditions. Fleet managers collect information from drivers and the whole organization benefits from this up-to-date information.

“The online editing options make it easy for a non-GIS user to input information,” said Lara Prades, head of the Geospatial Unit in the Emergency Division at the WFP headquarters.“ Warehouse operators quickly get it, because they have a GPS and GIS already in their brain and don’t even need to see a map. Now, the system captures their knowledge.”

The value of this information was quickly understood by different units within the organization and field offices across the country. WFP staff also share data and tools with other in-country partners, including UNICEF.

“The tool has been instrumental in supporting operations and access negotiations in Afghanistan,” said Robert Kasca, acting Country Director for WFP in Afghanistan. “In today’s highly complex operations theater, we cannot imagine working without modern mapping tools anymore.”

The new WFP system got its start four years ago to address the complex security challenges in Afghanistan. It has since evolved to incorporate many different aspects of WFP’s mission, including its assets, cash transfer program, food delivery and nutrition programmes.

“We would typically build a dashboard for security alone,” Prades said. “But this time, we brought all the datasets from different areas of WFP together.”

By merging all crucial data into one place, WFP staff could operationalize information—a move the head of security in Afghanistan considers a paradigm shift.

“An information-led operation has not been the case in the past and has to be the future. This system provides the core information I need to make important security decisions, and I can’t live without it. It would be like returning to running security operations blind—just reacting,” he said.

Learn more about how GIS is used to provide humanitarian assistance.

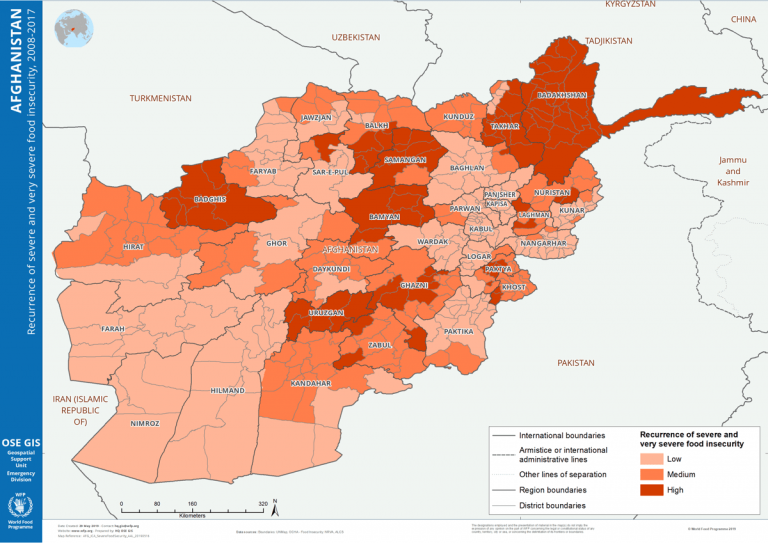

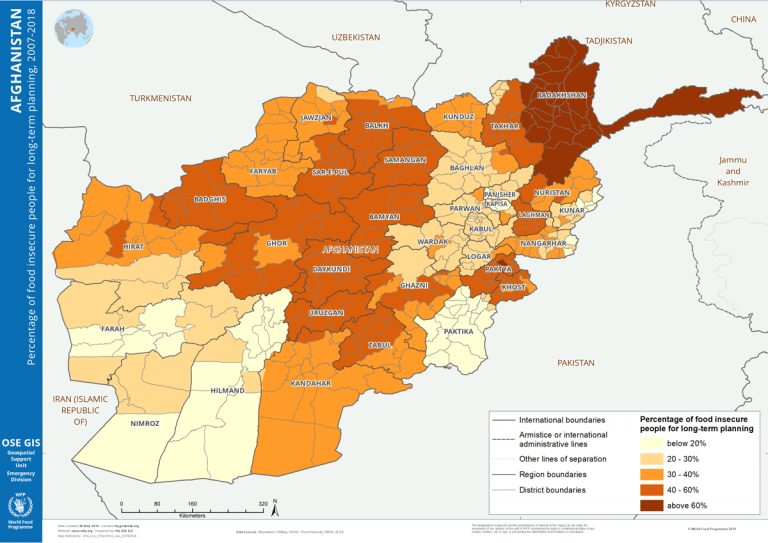

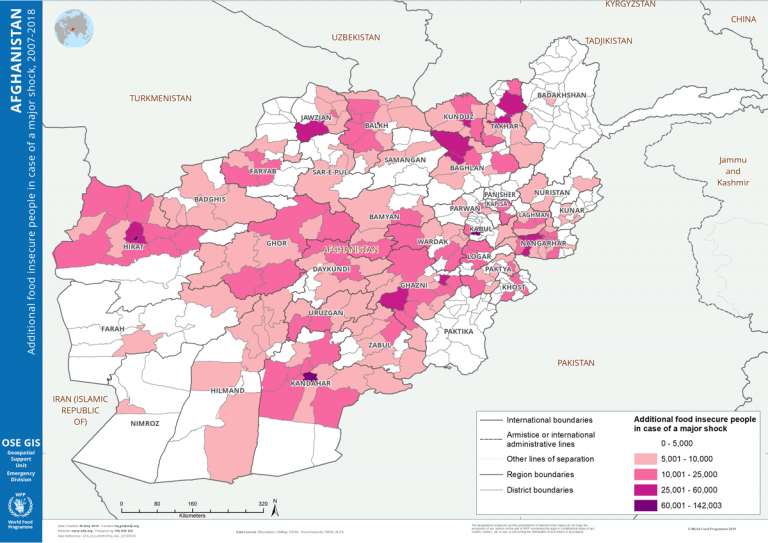

Below are maps related to food security that the WFP produces to share intelligence about areas of higher vulnerability. (Click on the map images to zoom in.)