May 2, 2022

Even with careful environmental stewardship and well managed forests, the white oak trees needed to make bourbon barrels have always been hard to find.

Twenty years ago, it was as much art as science—the best sleuths working to track down the trees that made ideal bourbon barrel staves. The quality and character of the wood matters because of its immense effect on the beverage’s color and flavor.

There’s a kind of magic in white oak.

Barrels made of white oak are not simply containers. They are crucial to the bourbon making process. The internal structure of the white oak—its cellular makeup—creates an ongoing exchange within the barrel where the liquid is drawn into the wood and then pumped out without soaking through the barrel.

Ideally, the trees must be 80 to 100 years old and should be growing in a forest tract that has steady weather, neither too wet nor too dry. If those conditions aren’t met, the heartwood doesn’t possess the internal cellular structure that makes for the best liquid-tight barrels and the finest bourbons.

In the past it was impossible to locate decades of weather records for rural, hilly, unpopulated areas to confirm historical patterns. So, even a trained forester, who was scouting trees for a big company, often relied on personal knowledge of the region.

Traditionally, the search for the best white oak was not only competitive among major distillers, but even had an air of secrecy. Just ask people like Bob Russell, a former forester who became something of a woodlands detective for the Brown-Forman distillery, makers of a variety of alcoholic spirits including Woodford Reserve and Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey. In his role at Brown-Forman, Russel had to figure out ways to analyze large swaths of forest over most of the eastern half of the United States.

Twenty years ago, Russell often had to rely exclusively on his own eyes, his instincts for promising places, and paper-based censuses of trees done by the federal government. If a forest area looked favorable, he might also see if it could be a good location to build a sawmill. Often, he would visit a potential site without drawing attention to himself, looking for clues. He’d watch the roadways and count the logging trucks passing by to get a sense of the forestry activity, economy, and workforce.

He kept a low-key presence to avoid tipping off competitors about Brown-Forman’s interest in the area. Recently retired, Russell had a career that spanned more than 40 years, including working as a forester, wood supply analyst, and, for lack of a better term, tree scout.

In his tenure at Brown-Forman, Russell was grateful for any tree census information the federal government could provide. Over the decades, he has seen the data and the analyses improve immensely with the help of geographic information systems (GIS) technology and the advent of what has been called a bourbon-barrel app.

“Just knowing where to go helps a whole lot,” Russell said of his early days in the industry. “And then seeing the Forest Service data and knowing how it’s collected and how it’s put together became a key in helping make those decisions.”

Empowered with that knowledge and his own boots-on-the-ground observations, Russell could help guide and sometimes even reverse decisions about where to build a sawmill, based on the number and quality of local white oaks, available road and river transport, and potential workforce.

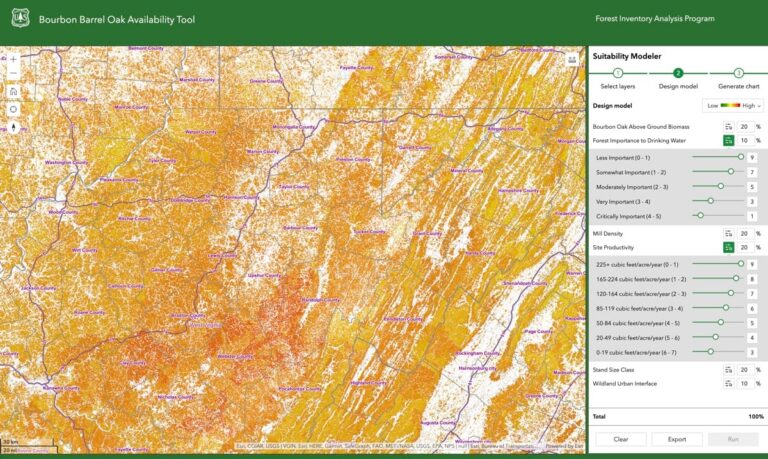

Today, the Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program of the US Forest Service has made its data more widely available online and more easily amenable to analysis by GIS. Developers from the US Forest Service and some in the spirits industry are creating apps to find stable areas of timber production and avoid places where the highly valued white oaks might become endangered from overcutting.

But even in the old days, the major producers knew they had to be careful to balance the need for white oak barrels with the need to ensure the survival of the slow-growing species. They realized early on that 80- to 100-year-old trees made the best barrel staves and had qualities that produced smoother, better-tasting bourbon. So, they could not afford to overharvest or create gaps in the staves supply line.

“They didn’t want to move into a landscape that was already being harvested pretty heavily and put even more pressure on the resource,” said Christopher M. Oswalt, a research forester for US Forest Service. “They have a long-term vision. They’ve got to keep these white oaks growing if they want to continue to produce the product that they do.”

Russell saw the spirits industry eventually gain better understanding of the multiple layers of data relevant to picking the right trees. But today, even with the help of the so-called bourbon-barrel app that uses GIS to produce location intelligence and then plot those results on a map, the hunt for the perfect trees is still difficult. There are many reasons for that, including laws that say bourbon must be made in unused barrels. Later, after the bourbon is bottled, the barrels may be used to age other alcoholic beverages, such as scotch whisky. But they cannot be reused for bourbon making. The law dictates that a fresh supply of white oak is needed, and it must keep pace with the popularity of bourbon and other spirits that use oak barrels.

In response, company leaders can use GIS-based location intelligence to map and analyze key variables such as age of trees; numbers of trees; climate history and predictions; records of insect problems; invasive trees and plants that can crowd out white oak saplings; types and numbers of wildfires in the region; and the quality of recent staves made from wood in specific locales.

For the bourbon industry, staves are not simply the curved planks of a barrel. They have qualities that seem a bit mysterious to outsiders.

White oak staves interact with the liquid, helping to age it properly while imparting sugars and flavors that create highly desired bourbons. Each company has its individual recipes, processes, and traditions for making bourbon that vary the way they char the inside of barrels to unleash flavors of caramelized sugars and vanillas from the wood.

The ongoing exchange imparts tastes, smoothness, and color that make up the distinct signature of every bourbon.

Brown-Forman and others use very nearly 100 percent of the white oak they purchase. They collect the bark to be used for fuel while the sawdust and wood chips are pressed into pellets to be used for cooking fires.

The US Forest Service handles data requests from many sectors—academia, the pulp and paper industries, and lumber companies. For distillers, they have recently been revamping the bourbon barrel app to reflect the multiple layers of data and type of analysis crucial to white oak logging and barrel making purposes. The app gives an at-a-glance view of the available resource, and users can adjust criteria to determine the most suitable locations that fit their needs.

“You could look for areas where white oak resources existed, where growth was positive in that white oak resource, and then also look where the density of mills was lowest,” Oswalt said. “And you could toy around with the different weights and so forth. Doing that highlights areas on the map that you might be interested in, and then you could click on the map and get a quick snapshot of what the resources within a 50- or 100-mile radius of wherever you clicked.”

With properly organized data and the ability to display the analyses spatially, the whole Forest Inventory and Analysis database will open up to many related industries, Oswalt said.

“One of the things that we’re really interested in is bringing our national woodland owners survey information to bear to these questions,” he said. “We hope to bring that data together much more comprehensively, and do so spatially, so all of that information is available for each place at the same time.”

With airborne drone surveys also a possibility in some areas of forestry, the older types of intense boots-on-the-ground investigations may become a fading memory.

Russell has seen a wide arc of change in the industry, and he hopes to see white oak continue to thrive and supply bourbon makers.

“Well, right now, white oak is pretty rare and valuable,” Russell said. “The demand is far outrunning supply right now. And so that’s forced the price of logs up. It’s forced the price of lumber up…So right now, it’s very precious. I’m expecting to see that crest and go back the other way. It always has over my last 43 years in the industry.”

Read how to use and configure the Bourbon Barrel Oak Availability Tool to answer supply questions. Learn how foresters apply GIS to improve management practices.