April 22, 2025

To understand why urban forestry has evolved from aesthetic landscaping into a science-driven cornerstone of city planning, you may need to change how you think about trees.

Today’s urban foresters are revolutionizing how we value trees, using advanced remote-sensing technology, digital mapping, and data science to quantify their benefits and advocate for preservation and expansion.

Beyond their beauty, urban trees deliver measurable ecosystem services: They sequester carbon, cool city temperatures, reduce energy use, filter air pollution, mitigate flooding through stormwater absorption, and support biodiversity. As these benefits are increasingly translated into dollar values, trees are also being recognized for their fundamental role in connecting humans with nature—a relationship with proven health benefits.

Deepening our appreciation for trees is necessary as two forces converge: the growth of cities and the intensification of weather patterns. Together, they threaten billons of trees worldwide.

As communities expand, urban forests now sit closer to population centers, maximizing their environmental and economic benefits. Urban foresters emphasize that these trees must be strategically preserved and managed to serve growing populations.

Using detailed imagery and mapping, these experts demonstrate how, without protective policies and thoughtful planning, tree canopies can diminish.

Urban forestry has evolved to secure trees’ place in increasingly dense cities where they’re most vital. According to the US Forest Service, urban forests have an economic impact in the billions of dollars: $5.4 billion in air pollution removal, $5.4 billion in reduced energy costs, and $2.7 billion in avoided emissions. Beyond economics, trees safeguard environmental health for many species, humans included.

We know this because modern tree stewards—arborists, geographers, and data analysts—analyze extensive data to illuminate trees’ essential role in vital communities.

Across a growing number of communities, elevating trees from mere amenities to essential assets marks the first step in prioritizing urban forestry. These living infrastructure elements now receive the same critical attention as other vital investments, supported by sophisticated research and technology systems that organize and guide preservation efforts.

“We’re engaged in asset management,” said Earl Eutsler, associate director of the Urban Forestry Division for the District Department of Transportation in Washington, D.C. “We invest in trees, and they become more valuable over time as they grow. And for that to happen, you have to have space where trees can exist near and amongst people.”

Urban land expanded by 14 percent in the US between 2000 and 2020, according to a report by the University of Michigan’s Center for Sustainable Systems. Meanwhile, tree cover in the United States is declining at a rate of about 175,000 acres per year. That amounts to the loss of about 36 million trees per year at a conservative cost of $96 million per year.

In Washington DC, known locally as the City of Trees, data science with geographic information system (GIS) technology provides a long-standing approach for monitoring, managing, protecting, and expanding forests.

The Arbor Day Foundation equips Tree City USA partners such as the District of Columbia with GIS mapping and NatureQuant data to help in identifying areas where trees can do the most good. This helps communities tell the full story of the value of trees.

After years of refining its tree management processes, the city now maintains detailed maps of all 200,000 trees in public planting beds, primarily along city streets. New construction projects must incorporate public planting areas to satisfy design and engineering standards.

Annually, city staff inspect roughly 63,000 trees while arborists plant about 8,000 new ones on public lands—in parks; at schools; and especially along city streets, considered the most challenging place to grow trees.

“If we’re not thoughtful about each of the decisions we’re making, we could be making 8,000 mistakes a year,” Eutsler said. “That’s why it was important for us to create a decision-support tool that our staff could refer to as they’re making the individual decisions that spool up into that annual investment in tree planting. We invest several million dollars a year and try to make it the most future-proof, future-ready investment.”

Future-proofing focuses on resilience or adaptation to changing weather patterns, such as extended heat waves. Investing in shade trees can make the hottest neighborhoods more livable, improve public health, and reduce heat-related deaths and energy use.

GIS maps provide a visual, street-by-street inventory for comparing year-over-year canopy growth and decline in the city’s eight wards. Those maps show the city’s required planting areas, located between the roads and the sidewalks, as well as details about the type and age of the trees growing within them.

A decade of GIS mapping, analysis, and predictive modeling now directs Washington, DC’s forest management strategy, pinpointing optimal planting locations and identifying the most suitable tree species for each environment.

Those historical records help identify shade-providing species with high tolerance for both current and future challenges—including intensifying cycles of drought and flooding and greater exposure to pests and disease.

“It’s too much information for any one person to know at the citywide level or even in the zone that they are individually responsible for,” Eutsler said. “We want to have meaningful granularity as well as scale that is relevant for making decisions that don’t exacerbate either a diversity issue or a climate adaptation and mitigation challenge. And so we’ve synthesized all these data sources and then brought in that spatial element to give people a sense of what is best to plant where.”

In Wake County—the largest county in North Carolina by population—the economy is booming. The gross domestic product jumped nearly 40 percent from $87 million in 2020 to nearly $120 million in 2023.

That prosperity is fueling population growth—an increase of more than 25 percent from 2010 to 2020, to 1.15 million people. That’s nearly three and a half times the national growth rate.

The tradeoff is that Wake County’s green, rural character is receding. County officials often hear complaints expressing lament over the loss of trees and farmland.

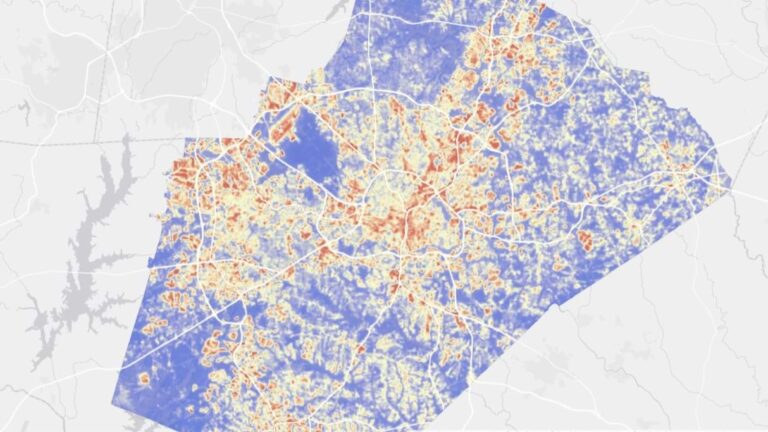

A 2022 GIS land-cover analysis, conducted with the environmental consulting firm Davey Resource Group, Inc., established a baseline for ongoing monitoring of Wake County’s urban forests, documenting tree species, locations, and health metrics throughout the landscape.

The study also defined how land in the county was used. Trees occupied more than half of the county’s land, and the rest was allocated to crops and other vegetation, buildings, bare soil, and bodies of water.

The land-cover analysis using remote sensing data from 2010 and 2020, showed that Wake County had lost 11,122 acres of its tree canopy—or 3.6 percent—over the previous 10 years. One-fourth of the county’s 597 US census blocks lost more than 5 percent of their tree canopy. That means trees in some locations are more vulnerable than in others.

“The technology is allowing us to gauge the change that’s happening between the built and the natural areas,” said Bill Shroyer, senior GIS analyst for Wake County’s Long-Range Planning Department. “We’re trying to work within that interplay of development and urbanization to bring back some of the natural elements. It’s brought to the forefront an emphasis on policy to reestablish tree canopy.”

County officials use GIS maps and spatial analysis to uncover opportunities and risks. Based on those insights, they establish and rank priorities to ensure that communities continue to make room for nature.

GIS analysis shows that over their life span, Wake County’s trees have already removed and stored more than 10.2 million tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and absorbed an estimated 8.1 billion gallons of stormwater.

That’s especially important in the city of Raleigh, where 8 percent of homes are prone to flooding. Excessive stormwater runoff can damage trees in low-lying areas as well as carry debris and other pollutants into creeks, streams, and other water sources.

County analysts calculated that trees have prevented more than $3.2 billion in damage to human health, property, and the environment. Now the county is working to ensure that trees are healthy and abundant enough to continue providing these benefits to the community.

Planners mapped more than 82,000 acres that are suitable for planting to replace trees lost to development, or to add trees in an effort to prevent soil erosion and flooding.

Tree planting will also help cool the county’s hottest neighborhoods—often located in communities with higher rates of poverty and health disparities. Planting more trees to help cool the hottest neighborhoods has become a strategy for mitigating heat waves that linger in many US cities.

In Wake County, analysts also identify land that is unsuitable for planting trees. Those areas often are public rights-of-way and easements.

Within the land available for planting, analysts can sharpen their focus to study and address threats that could hinder the health of established or young trees.

Having data for each census block allows planners to investigate and craft solutions specific to each location. That new level of precision improves the health of trees and allows staff to use county resources more effectively.

“It gives us an opportunity to be so granular that we can put groups on the ground and find out what is affecting change,” Shroyer said. “It’s more than just knowing where the majority of the trees have disappeared. It’s actually knowing why.”

Learn more about how foresters use GIS for sustainable forest management.