In a full third of the country there is a dearth of treatment capacity. It’s just not existent.

June 27, 2019

A conversation with Dr. James R. Langabeer II, professor of biomedical informatics, emergency medicine, and public health at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), and leader of the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System (HEROES), a comprehensive system of care for managing opioid use disorder.

Opioid overdoses have claimed more than 400,000 lives since 1999, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemic has accelerated to the point where Americans are more likely to die from an overdose than a car accident or shooting. These startling statistics prompted the president to declare opioid use disorder a national public health emergency.

James Langabeer, PhD, MBA, a cognitive scientist and health services researcher, is tackling this epidemic at both a national and local level. Nationally, his research focuses on the determinants of death and treatment success. Locally, he leads the HEROES program, a collaborative partnership with the Houston Fire Department, Houston Police Department, Houston Recovery Center, and Memorial Hermann Hospital-Texas Medical Center.

This conversation covers the use of GIS in both Dr. Langabeer’s research and outreach, touching on proven patterns and practices.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

How do maps and spatial analytics aid you in understanding trends in opioid use disorder?

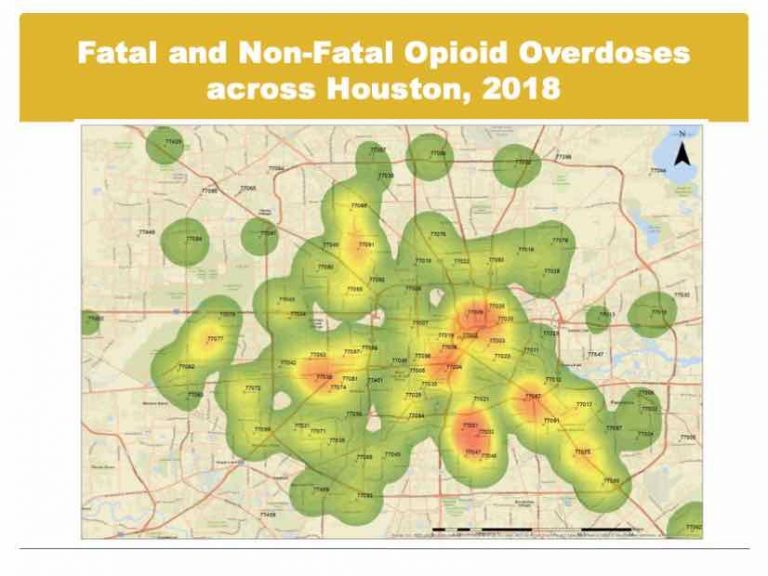

We can run statistical and analytical models and come up with fancy equations, but they don’t often put data in terms that people can readily understand. Visual analysis and geospatial analysis specifically have proven more useful in describing problems and pinpointing where we should place our efforts.

Do you use GIS in your daily practice?

Yes, we map everything. Geospatial models are very important to us on a daily basis. We map where people are dying from drug overdoses using data from the local medical examiner’s office. We also map and analyze where people are overdosing based on data from the fire department. We look at national data from the CDC. We use all available data to identify priority zones to target.

We also use the data to detect changes over time, comparing this month or this quarter with data from the past. This helps us understand progressions of drugs, movement of dealers, and the disease. We don’t necessarily understand why it’s happening, but the data and the analysis helps us to understand where it is, and to try to dig deeper for the triggers.

Have you uncovered any patterns to understand the spread of opioid overdoses across the country?

We have developed a statistical model with county-level data on social, health, and economic determinants. We looked at the relationship between where people are dying and the opioid mortality rate. Our goal is to figure out which of these factors are most associated with death. In some areas, the determining factor could be the economy.

We have also looked at factors that determine what keeps people from staying in recovery. Homelessness is a factor as are medical issues, including hepatitis C or HIV.

We’re working on interpreting our data and digging deeper to understand it.

What’s different about how the HEROES program tackles opioid use disorder?

The HEROES program takes a long-term approach that links medical treatment, behavioral treatment, and peer recovery support. We have fostered a community-wide collaboration, getting police, fire, and hospital emergency departments to talk with traditional outpatient medical treatment providers, psychiatrists, and family medicine practitioners. Traditionally, these groups do not communicate regularly.

Normally, treatment is one-on-one, with little collaboration regarding an individual with opioid use disorder. We’re trying to link everyone in the public safety and healthcare community around people who have this problem.

Have you achieved results with your data-driven actions?

We have had success rapidly identifying individuals who have overdosed or are in frail condition with a high potential for an overdose. We work to identify them, pinpoint their location, and get people mobilized to initiate treatment proactively rather than waiting for them to show up for treatment.

We send a paramedic and a peer recovery support specialist, someone who has the disease but has been sober many years, to do assertive outreach. They knock on the doors of people who have overdosed in the past and try to recruit them into treatment at no cost to them. A number of people come into treatment that have never committed to treatment before.

We know we’re saving lives because we’ve studied the number of overdoses and the number of deaths occurring locally, and we’re able to see the impact.

In a full third of the country there is a dearth of treatment capacity. It’s just not existent.

What’s your approach to treatment?

We really need to think about treating this disease with a multi-factorial approach with a lot of things in place. Our treatment begins with medical treatment. We prefer people to be on buprenorphine rather than go cold turkey. You have to be in some kind of behavioral treatment as well. Every participant in our program goes through addiction counseling and they have access to licensed psychologists. The third component of our approach is to surround participants with positive peers that have made it through treatment.

We really think you have to have all three of these things in order to adapt the brain for a long-term recovery. It’s very difficult to break the chains of this disease.

In your recent paper in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, you look at disparities between opioid overdose deaths and treatment capacity across the US. Do you think meaningful change will require policy changes?

We see a lot of policy changes that are necessary in terms of creating new capacity, as well as how providers are incentivized to treat this disease. In a full third of the country there is a dearth of treatment capacity. It’s just not existent.

Even where the capacity exists, the wait times can be very long. Another real problem is that the treatment centers may only take people with cash or with a certain insurance. People with opioid use disorder have a brain disorder that causes a series of bad choices. Many lose their job, their health insurance, their family and friends, and everything else. Policy change is necessary to create flexible and affordable treatment capacity.

To reduce the harmful effects of the epidemic, where people are using substances and dying from them, we need better public health policies. Programs being considered include safe injection sites, needle exchange programs, making Narcan overdose treatment widely available, and other harm reduction policies. All can have an impact.

Learn how communities apply GIS to Get in Front of the Opioid Crisis.