August 4, 2021

To understand the complex variables and changes in natural cycles that impact threatened species, conservationists are using sophisticated mapping techniques and geographic information system (GIS) technology.

Consider the gopher tortoise and its unique relationship with forest fires.

The gopher tortoise is resilient to the occasional forest fire because the long tunnels it digs and inhabits 10 feet underground are fortified enough to withstand the smoke, flames, and burning debris.

Maintaining this subterranean lifestyle requires very specific habitat conditions. The sandy soils of the pine savannas found throughout the southeastern United States are particularly welcoming.

Over time, as the pine trees grow, the forest density threatens the vegetation the tortoises eat. Before major human contact, naturally occurring forest fires—often caused by lightning strikes—would help preserve this understory vegetation.

The modern fragmentation of the forests—through the introduction of roads, homes, croplands, and cities—has disrupted this cycle. Without fires, the forested areas that remain have become overgrown.

The decline of fire-adapted forest ecosystems is not the only factor that threatens the gopher tortoise, but it underlines the complexity of the fight to protect the endangered creature. The South Carolina Natural Heritage Program is arguably their most powerful ally.

The Natural Heritage Program—and its Cultural Heritage counterpart, dedicated to preserving land with historical and cultural relevance—together form the South Carolina Heritage Trust Program, a section within the state’s Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR).

The work of the Heritage Trust began in the mid-1970s. Shortly thereafter, when the project was transferred to SCDNR, the state agency became the first state in the country dedicated to protecting land with abundant natural or cultural significance.

From the start, the work relied on one of the earliest desktop GIS software programs. As GIS software grew more sophisticated, Heritage Trust adopted an ArcGIS Enterprise approach. The technology became central to many of the program’s objectives, including mapping habitat loss and picking areas the state could purchase for permanently protected heritage preserves.

With GIS, conservationists can analyze how and where to develop land in ways that protect biodiversity.

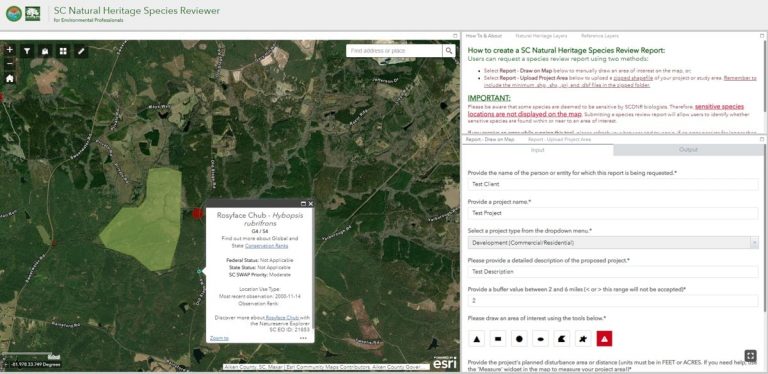

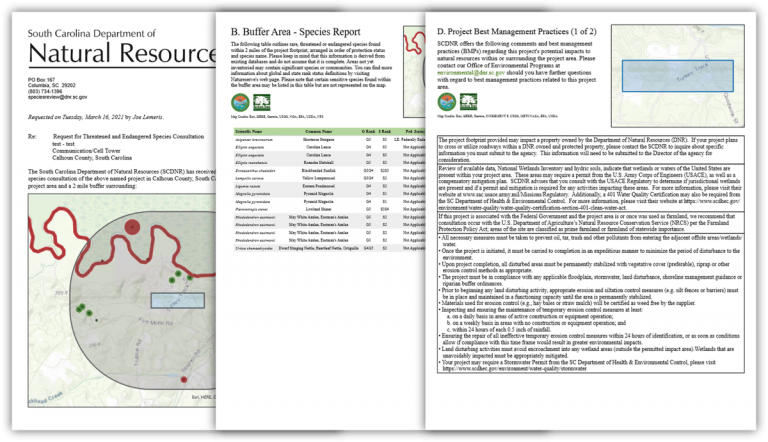

The Natural Heritage Program recently expanded its GIS to facilitate better communication with stakeholders, including private developers, scientists, and the public. Communication and workflows have always been challenges, especially regarding due diligence for developers proposing new projects. Any development that receives federal government financing or permitting must review the presence of threatened or endangered species within the proposed project footprint.

Until recently, developers would submit requests with varying degrees of specificity. Some contained only geographic coordinates, others included maps, and some were just general descriptions of the area. The office would check requests against its database of protected flora and fauna, struggling to get through around 200 requests per year.

“It was a long, drawn-out process, and it wasn’t even our full-time job,” said Joe Lemeris, the program’s GIS and data manager.

The inefficiency extended to the workflow used by scientists who gathered data from the field. They recorded their observations onto Excel spreadsheets or paper forms. At some later date, this information would become part of the program’s database. The office also gathered data from other civic and private partners, including the US Fish and Wildlife Service, which could arrive in various formats, adding more process bottlenecks.

“The problem with the way it was done before is that the consultants could say they’d done due diligence, and that we’d shown them everything we had on a species, but then more data could pop up after we’d shared what we had,” Lemeris said.

A few years ago, a proposed solar project northwest of Beaufort, South Carolina, put a spotlight on the outdated system. The developers consulted information previously obtained from the Natural Heritage Program database, unaware that data gathered more recently showed that current project plans threatened the gopher tortoise’s habitat.

The problem, as Lemeris saw it, was that everyone was dealing with “static data”—information frozen in time as the world moved forward. What the program needed was a dynamic system that would reflect the most recent findings.

The solution was to take advantage of recent developments in GIS that prioritize the storage and flow of geographic information as well as its visualization. Data is now added and accessed through the same GIS-enabled portal. “It’s essentially just a web app, and we added a custom-designed reporting tool,” Lemeris said.

Scientists conducting field surveys input their data into ArcGIS Survey123 forms connected to the database.

“They have access to the data being collected in a way that goes beyond just writing it down in field notes and then having to transcribe it into a spreadsheet,” said Tanner Arrington, GIS manager for SCDNR. “They gain a locational context that they didn’t have when the data was just tabular. With location attached to it, they can see patterns that were unknown before.”

The GIS data can be presented with varying degrees of specificity, depending on who wants to see it. For certain species, the Natural Heritage Program prefers not to share its survey data in granular detail, opting instead for a more generalized view.

The black rail bird merits this opaque approach. This bird’s tiny stature restricts it to wetland areas with less than an inch of water. Unlike most birds, they spend more time running through marshes than flying through air.

For many years, no black rails were sighted in South Carolina, and the bird remains on the threatened list under the Endangered Species Act. Recently, birdwatchers have logged black rail sightings in the state. While this is good news, birder enthusiasm can present a problem.

If the exact location of appearances by the black rail are revealed, the influx of birders may damage those spots. On the Natural Heritage Program’s maps, only those with special permissions—scientists, mostly—can study exactly where rails have appeared. Others, including developers, will see general areas marked off as the bird’s habitat.

The success of the South Carolina Natural Heritage Program’s portal has already paid dividends in increased efficiency. Lemeris estimates the tool has quadrupled the number of requests the office can process. The ease of use also encourages more developers to submit requests for data.

“I think there were a lot of people who weren’t submitting projects to us because it was slow, and every day is more money,” Lemeris said, “and also because it wasn’t made very easy for them.”

Other offices within SCDNR, as well as other state natural heritage programs, have also taken notice. “There’s been a ripple effect,” Arrington said. “The original understanding of the technology was through desktop GIS. But now that more people have seen what enterprise GIS is capable of, it’s opened new opportunities within the agency. They’re saying, ‘Well, if it works for the Heritage Program, why can’t we give it a try?’ They’ve seen the benefits firsthand, and that’s very powerful.”

Learn more about how organizations and policy makers help preserve biodiversity with GIS.