August 1, 2023

Can a Historic Hawaii Community Modernize without Losing What Makes It Unique?

Kaumakani, a name that translates from the Hawaiian language as “place in the wind,” is a former sugar plantation camp founded in the late 19th century on the island of Kauai.

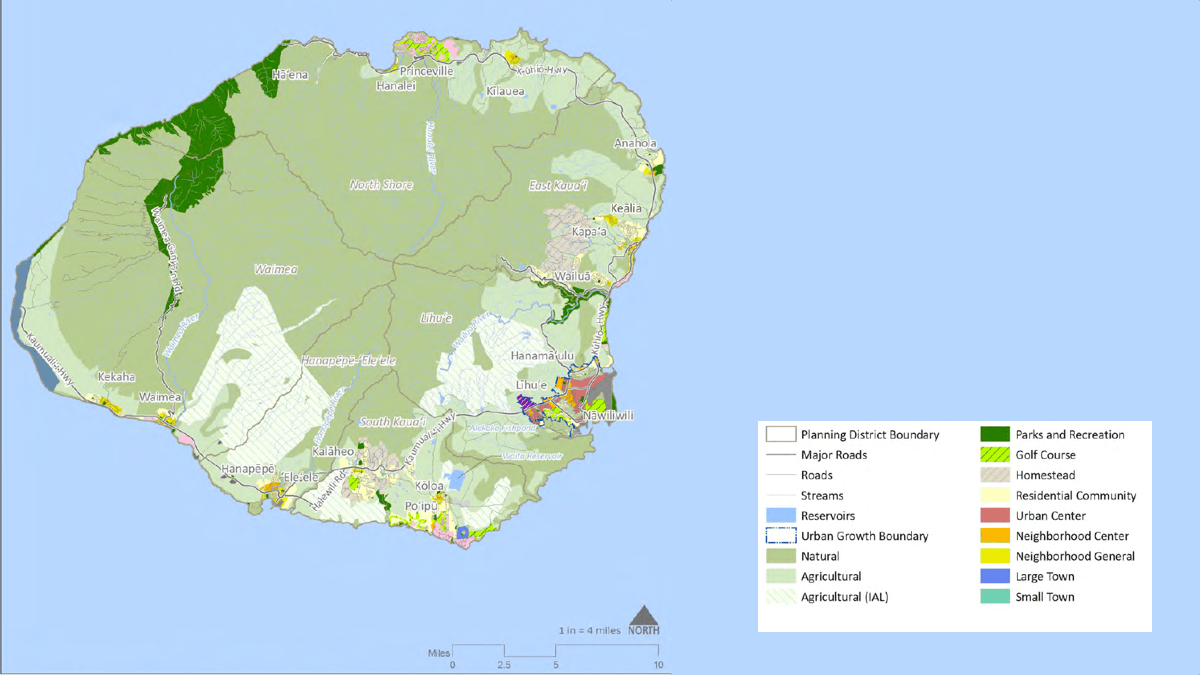

Kauai, known as the Garden Isle because of its lush landscapes, is the fourth largest of the Hawaiian islands and has served as the backdrop of numerous films, including Jurassic Park and Avatar. Kauai is home to less than 5 percent of Hawaii’s people and the population of Kaumakani—around 720 people—is less than 1 percent of Kauai’s.

On any given day, nearly one-third of the people on Kauai are tourists. They have no lasting stake in Kauai’s future, but their connection to Hawaii’s major economic driver can slant the island’s power dynamics, stifling the voice of Kauai’s permanent population.

A small rural settlement like Kaumakani is especially vulnerable. That’s one reason the planning department for the County of Kauai uses maps and geographic information system (GIS) technology to help protect Kaumakani’s unique character. A recent survey of the area gathered details and enshrined them in a new type of building code, protecting Kaumakani’s roots from cultural erosion.

Island Camps

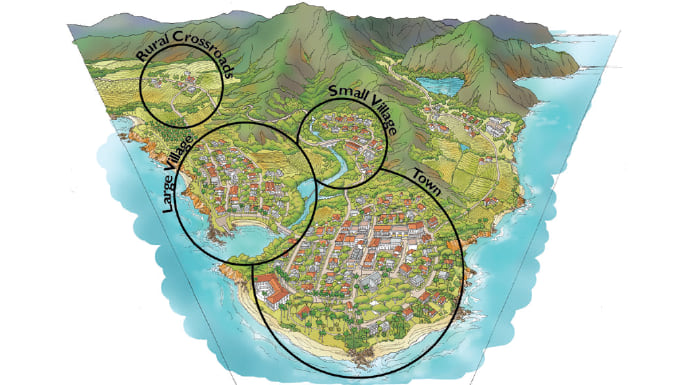

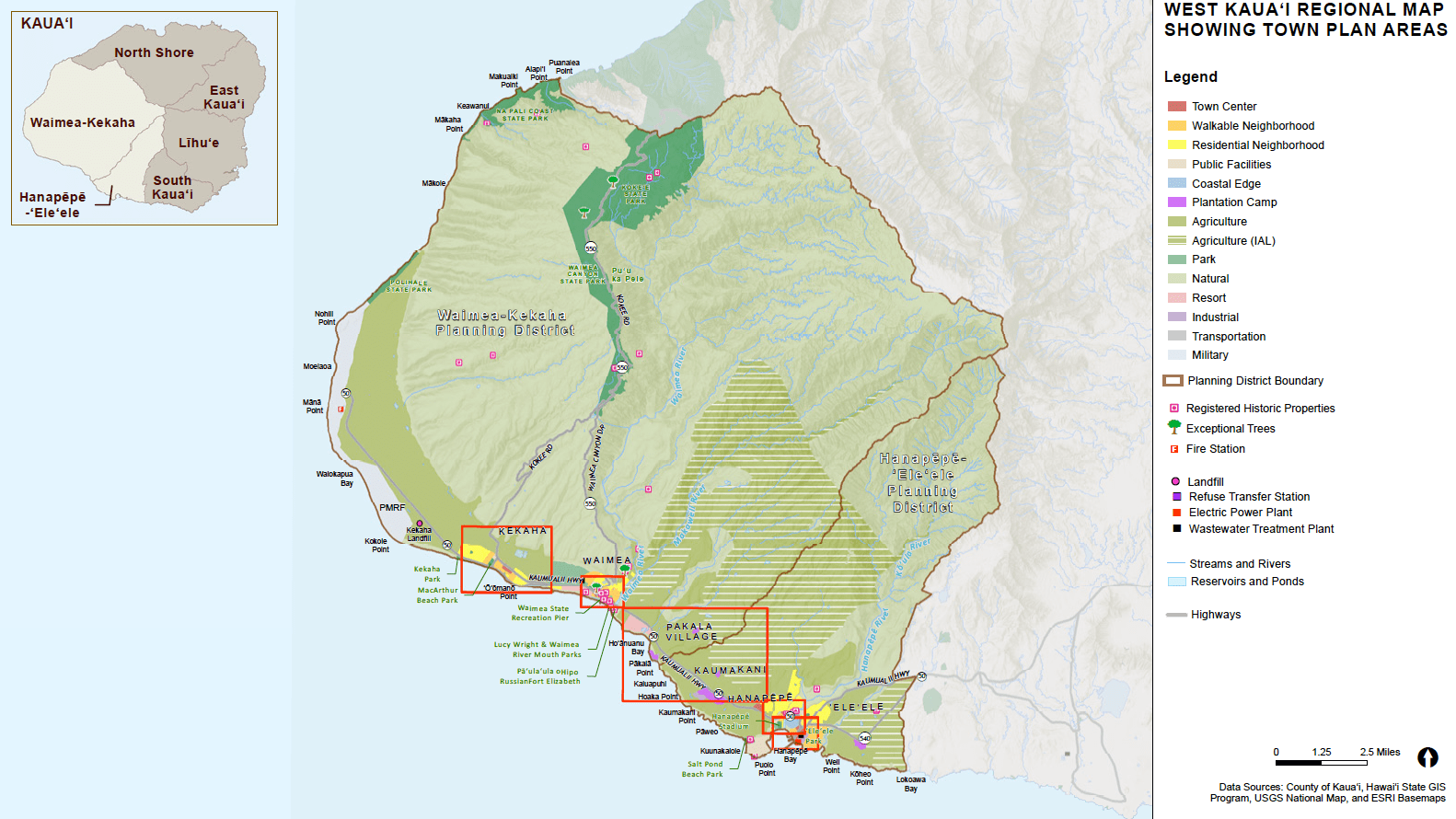

Sugar is no longer a viable industry on Kauai, but several of the plantation camps it generated still survive as contemporary housing. As the County of Kauai’s Planning Department noted in its recent general plan—which received the American Planning Association’s most prestigious award—the camps occupy a unique place in the island’s history and culture.

Their location, surrounded by sugar cane fields, “created a greenbelt that differentiated towns from agricultural and natural areas,” the report noted. “This relationship between built areas and surrounding natural or agricultural lands heavily influences [the island’s] character [and] rural identity.”

The pedestrian-oriented scale of the camps fostered walkable communities, even with the rise of the automobile. That communal feel remains today. However, the camps’ relative isolation and paucity of services—Kaumakani has a single, small retail area—make residents largely car dependent.

The general plan includes a commitment to “revitalize, restore, and celebrate these characterful towns that promote healthy economies and community life.” Kaumakani appears in the plan as one of five priority equity areas, given its makeup of largely low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. Recently, planners had to navigate the tension between preservation and adaptation.

Past and Present

Most of Kaumakani’s modest homes—relatively low-cost rentals—were built in the 1940s, before the sugar plantation changed ownership. In 2022, Kaumakani’s current owners expressed an interest in demolishing and replacing some of the unoccupied homes that had fallen into disrepair. The owners also wanted to build new structures on the camp’s mostly vacant fourth quadrant.

Planners had to look closely to determine what the land owners would be allowed to do—and to detail how they would be allowed to do it.

“The thing that’s so unique about this area, and which required a different approach, is that it’s just one big property with no lot lines, built before there were any complex zoning ordinances,” said Alan Clinton, an administrative planner for the county.

The planning department would have to start from scratch, formulating a code that would articulate what makes Kaumakani Kaumakani.

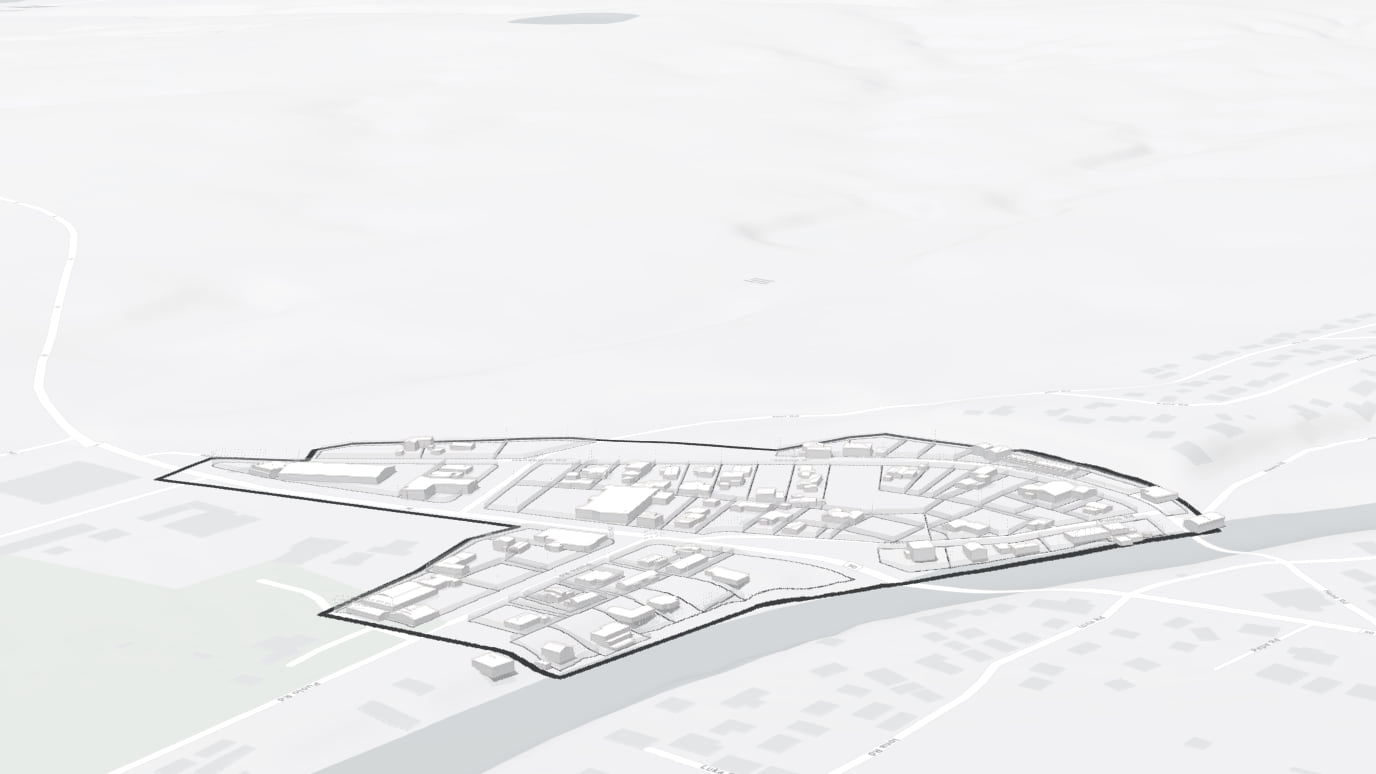

County planners walked the streets, observing the form and layout of the neighborhood. They carried mobile devices loaded with ArcGIS QuickCapture to gather relevant details and place them on a shared map. All information—pictures, notes, data—populated this map.

“To write the code, we made a lot of measurements, took photos of everything, and put together a series of features,” Clinton said.

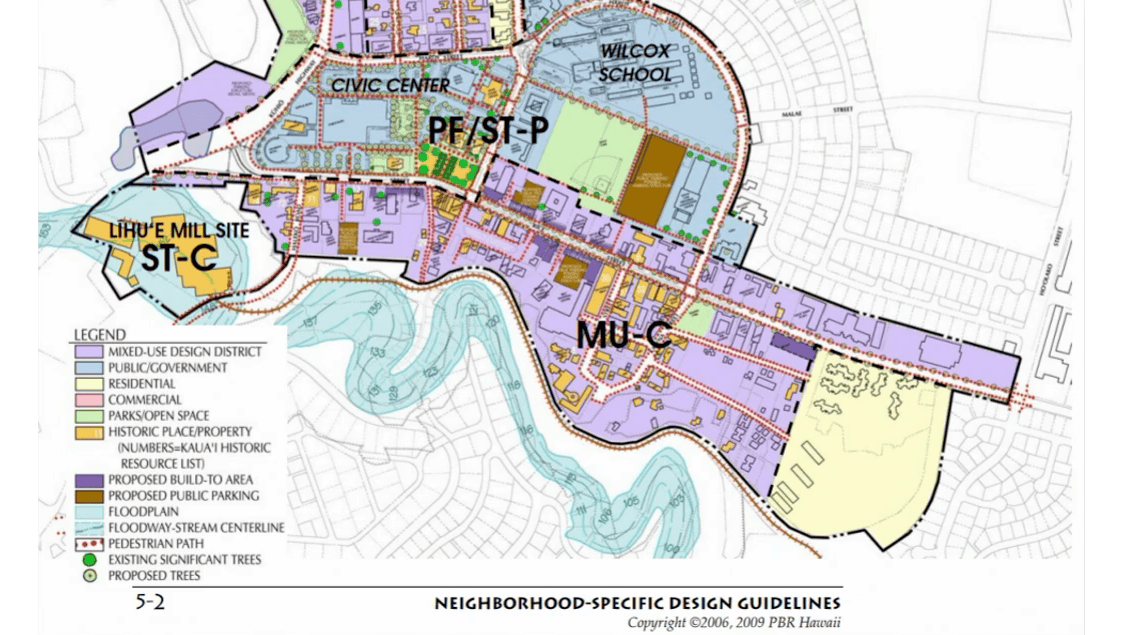

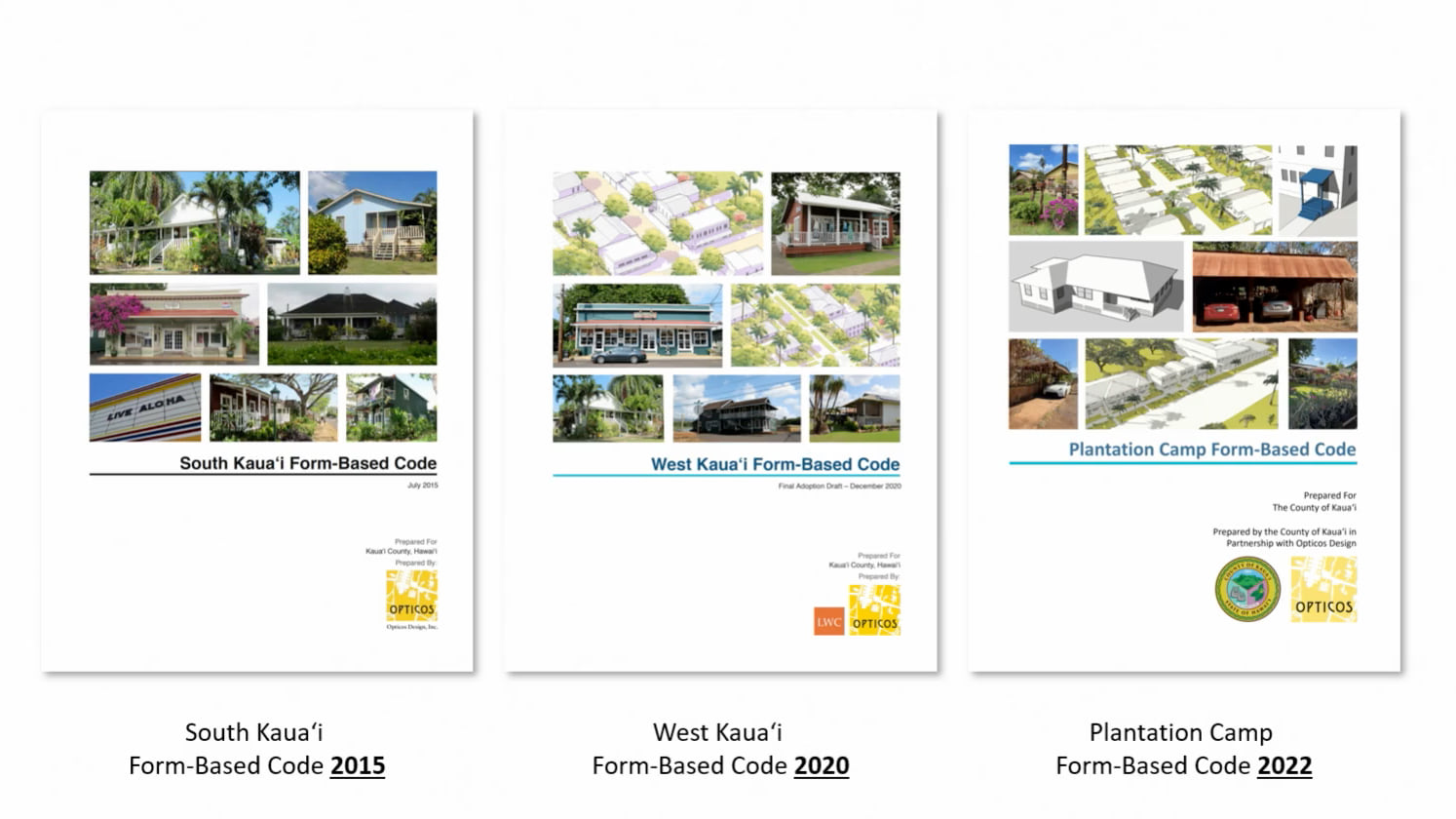

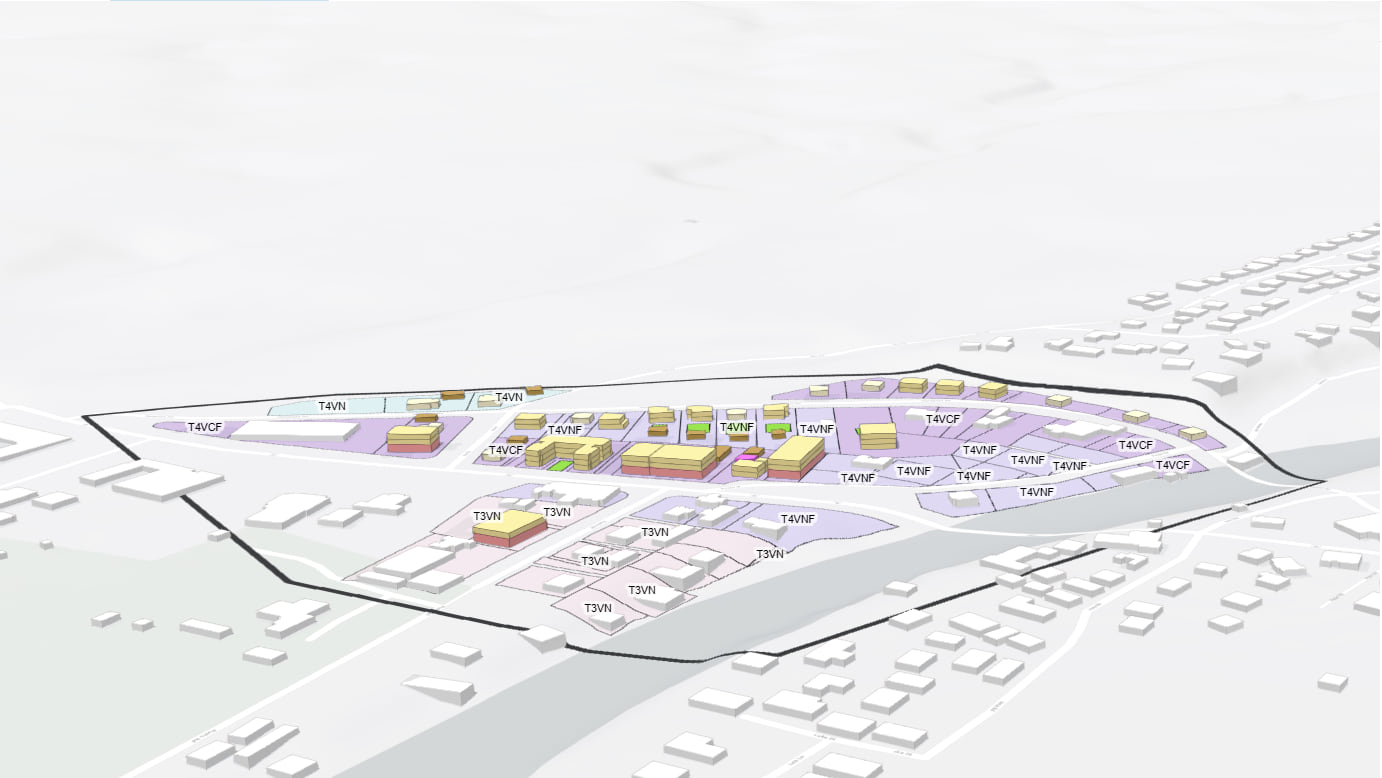

As the map developed, it revealed patterns that helped the planning department define the formal elements the landowners needed to include in their structures. The code was appended to the 300-page West Kauai Form-Based Code.

Besides describing how the homes should look to conform to the plantation architectural style, the planners also wanted to preserve the way private housing and public street life were closely intertwined in Kaumakani. The new code defined the allowed frontage, the maximum amount of space between a building’s facade and the street.

Carport Confidential

The map, and the building forms within it, revealed fascinating details about the essential characteristics of Kaumakani that would likely have gone unnoticed otherwise.

Clinton pointed to an aerial view provided by the department’s Kaumakani map. “You’ll notice that all these homes have a main central body and a carport on the side,” he said. Close observation and an understanding of local culture helped the planners understand the carports’ significance.

“Oftentimes, planners will say parking in the front is bad,” Clinton said. “But these carports are really more like outdoor living spaces. They’re places where people eat, or even live. They’re kind of extensions of the houses’ interior space.”

The carports were never part of the original design of the houses. They had appeared organically, added to the properties over the years by individual tenants.

The property owner, which had already begun to build some of the replacement homes, had missed the carports’ significance.

“We told them, ‘Sorry, guys, but this is part of the form and character of the camp,’” Clinton said. “The carports are a defining element that we wanted to make sure was included.”

Clinton pointed to interesting detail from the map. On one quadrant, the homes had been built with a vertical orientation to the street, while in another, they varied, forming a neat pattern that alternated between vertical and horizontal. As carports had been added over the years, tenants had followed these patterns.

The lack of formal lot lines made this all the more remarkable. The patterns had emerged without guidance and likely without discussion among tenants. They are now part of Kaumakani’s building code.

The Move to Foreground Form

In Hawaii, the concept of land planning taps into a unique historical and cultural vein. In the Indigenous Hawaiian belief system, the concept of land—or aina—implies not just the ground itself but also the connection between people and place. The concept of aloha aina (love of the land) is a deeply rooted tenet with connotations of patriotism. The local word used to describe a resident of Hawaii—kamaaina—translates literally as child of the land.

The general plan for the island reflects the department’s understanding of these ideals. It was assembled with extensive community input, including informal “talk story” sessions, a local term that refers to casual conversation.

These sessions influenced the planners’ approach to applying zoning ordinances to plantation camps like Kaumakani. Feedback from camp residents included the importance of community childcare centers and the interest in adding yurts or tiny homes to increase the amount of living space.

One way the department demonstrates its respect for a historically rich neighborhood like Kaumakani is via a modern approach that runs counter to traditional urban and regional planning orthodoxy.

“Planners have usually divided land into usage categories—like, this area is for industrial purposes; that one is for single-family homes,” Clinton said. “But over the years, focusing on use hasn’t always supported the historic areas people love and enjoy.”

The alternative approach—form-based zoning codes—retains usage categories while adding humanist considerations. Function, to varying degrees, follows form.

“Form-based codes highlight form and character over use,” Clinton said. “We create a whole new zoning code that focuses on building types, how structures interact with the street, and how the form and character of buildings fit an area.”

The philosophy is similar to that of the geodesign movement, which advocates close analysis—often using large amounts of data. The goal is to understand and predict how people will experience a built environment and to minimize human impact on the natural world. Not coincidentally, both approaches adopt GIS as a way to gather and process information.

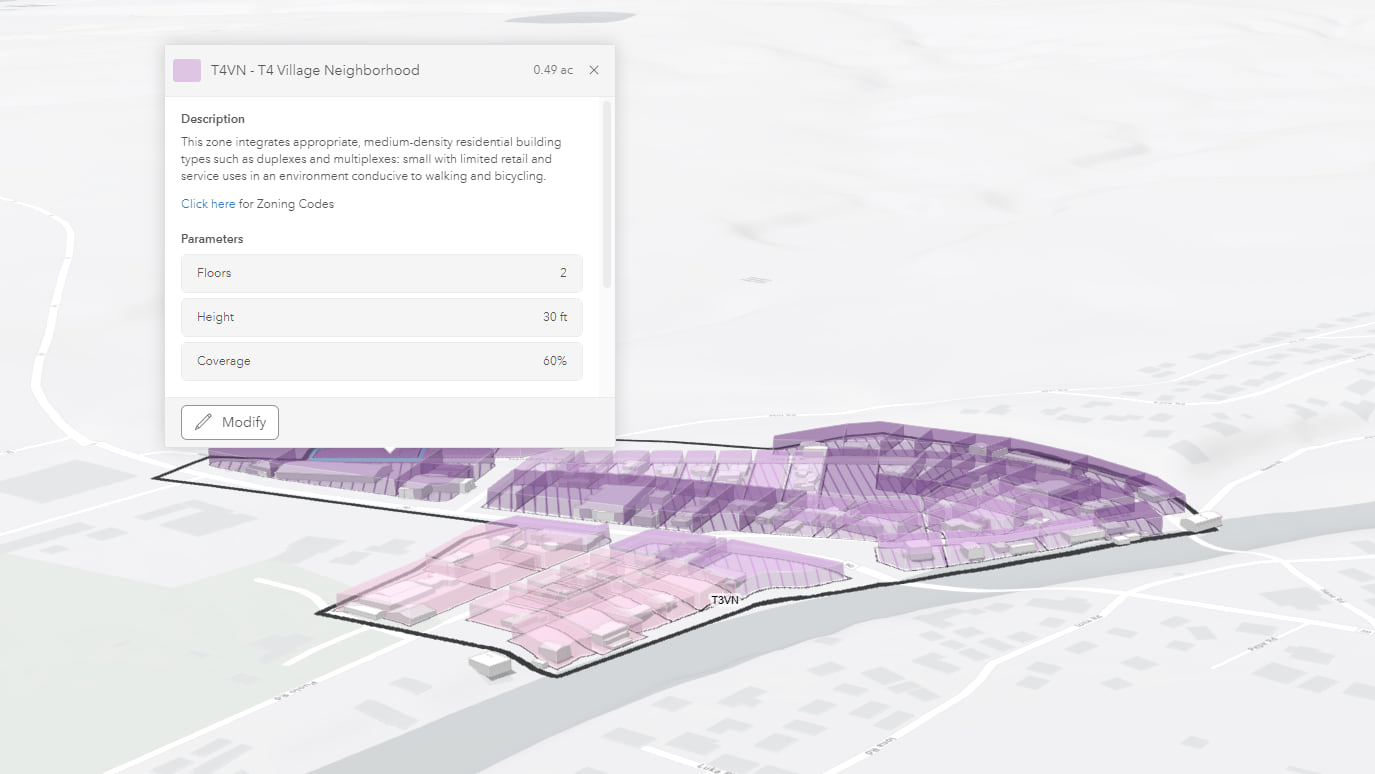

Form-based codes can seem baffling to developers accustomed to thinking solely in terms of usage categories. Now, anyone building land—or making changes to an existing structure—covered by the West Kauai Form-Based code can click on parts of the map to understand which aspects of the document relate to a particular structure or area.

Clinton said that his department has been approached by groups interested in form-based codes as a means of restoring and preserving other Kauai towns and settlements. Since many of the original structures are gone, historic photos will form the foundation of the new codes.

The planners also intend to make GIS maps a bigger part of the community outreach process. They want to use maps to help locals articulate what they consider essential form and character.

“If we were to just dictate usage, it wouldn’t create the kind of developments that communities want,” Clinton said. “Form-based codes take more work on our part, but we’re OK with that.”

Learn how planners review and track development projects with GIS.

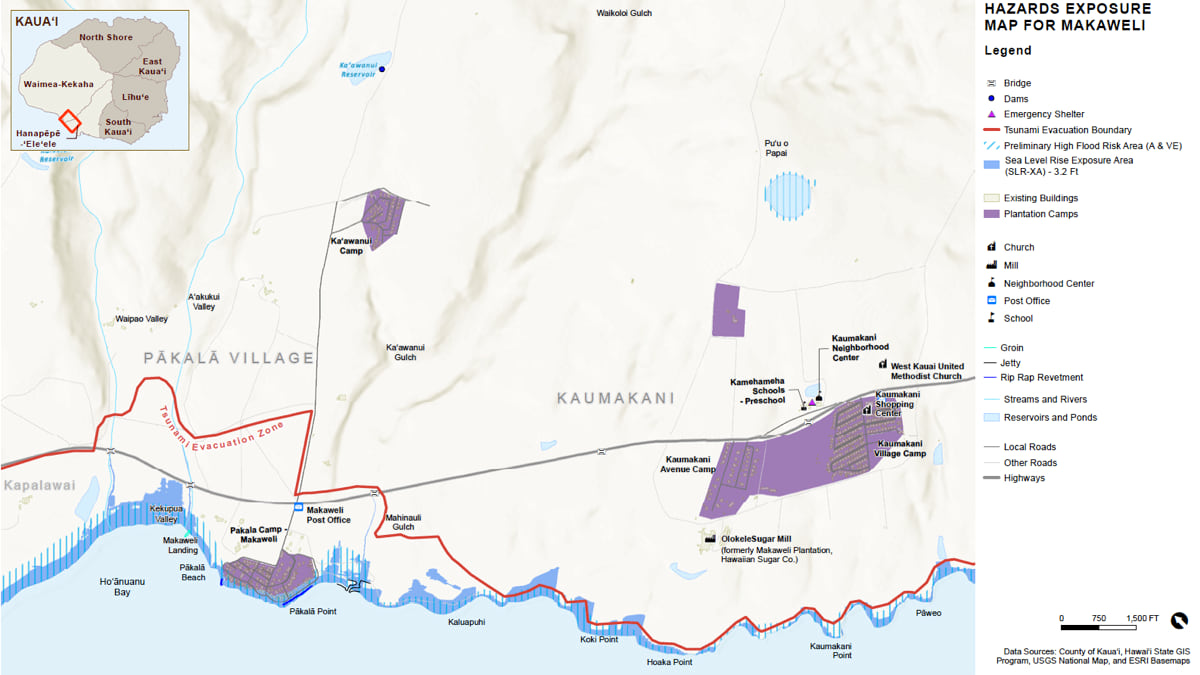

Considering Climate Impacts

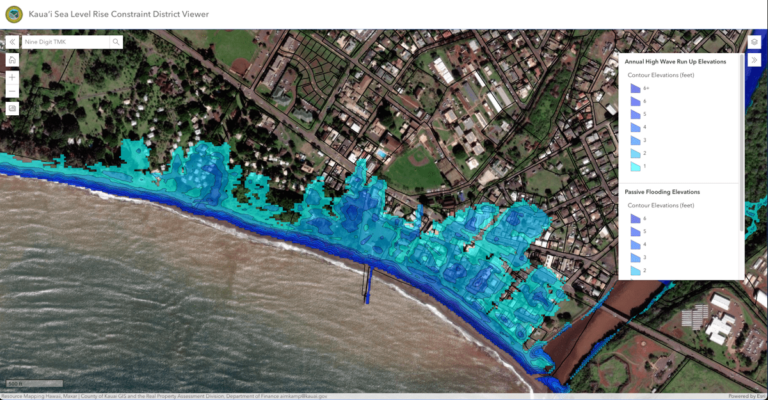

Kauai faces growing pressures from sea level rise. The Planning Department recently adopted the Sea Level Rise Constraint District to prepare Kauai communities and infrastructure for future climate-related hazards. In their effort to help communicate and implement this policy, planners developed the Kauai Sea Level Rise Constraint District Viewer and a Hazard Report Generation tool.