July 25, 2023

The above aerial photo shows peatlands in the Hudson Bay Lowland. (Photo credit: Lorna Harris)

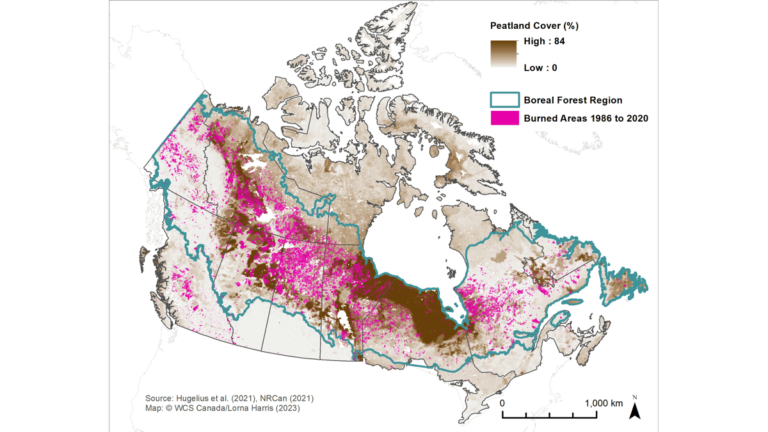

Canada’s 1.1 million square kilometers of peatlands—one of earth’s largest natural carbon stores—are a little-known but crucial aspect of the country’s current wildfire crisis across the boreal forest region. In 2023, between January and mid-July, more than 24.7 million acres of forest burned, spanning from Alberta to Quebec. The wildfires were so expansive, the smoke blanketed most of the East Coast of North America, from Nova Scotia all the way south to Florida. The worst air pollution in the world on June 6, 2023, was in New York City. The health impacts of the wildfires across Canada sent a clear signal about the costs of climate change.

Peatlands are wetland ecosystems where waterlogged conditions capture plant material and keep it from fully decomposing. Peat is essentially young coal. When wildfire approaches, if the ground is wet and spongy—as it is when healthy—it can slow or stop the fire. But when it dries out, it can do the opposite and be a potent fuel for fires. Many degraded and disturbed peatlands across Canada have been drying for some time, extending the firefighting challenge.

Remarkably, Canada contains 25 percent of the world’s peatlands, which hold a stunning 150 billion tons of carbon. Due to human encroachment, industrial disturbances, and the ongoing impacts of climate change, the critical carbon storage and climate-mitigation capabilities of peatlands are in danger. Permafrost thaw and greater fire frequency and intensity add to the threats to these vital but vulnerable lands.

Wildlife Conservation Society Canada (WCS Canada) is working to ensure peatlands continue to serve an essential climate change mitigation function. The organization applies geographic information system (GIS) technology to foster a fundamental shift in how peatlands are assessed and managed in Canada.

“Over the past couple of decades, GIS has become a useful tool for peatlands work, especially for these large landscapes,” said Lorna Harris, director of the Forests, Peatlands, and Climate Change Program at WCS Canada. “Having an idea of the different peatland types, where they are, and how they connect can help us understand where the water is flowing across the landscape and what plant communities are within an area.”

WCS Canada uses GIS to measure peatland cover and carbon storage, record the lands’ protected status and risks from development (e.g., mining claims), inform fieldwork, and prioritize conservation efforts. Researchers take maps into the field to verify map accuracy and add on-the-ground observations in a process that achieves what is called ground truth.

Only 13 percent of Canada’s peatlands are protected. The remaining 87 percent are at constant risk from development and industrial activities like peat extraction, logging, and mining.

The Hudson Bay Lowlands, which spans the northern portions of Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec, is the second-largest peatland complex in the world, and it’s under pressure. Within the Hudson Bay Lowlands sits the Ring of Fire, a vast mineral-rich region with deposits of chromite, nickel, copper, gold, zinc, and other minerals. Mining in this region is subject to ongoing debate, with the possible economic benefits being weighed against globally significant environmental concerns and the rights of Indigenous communities.

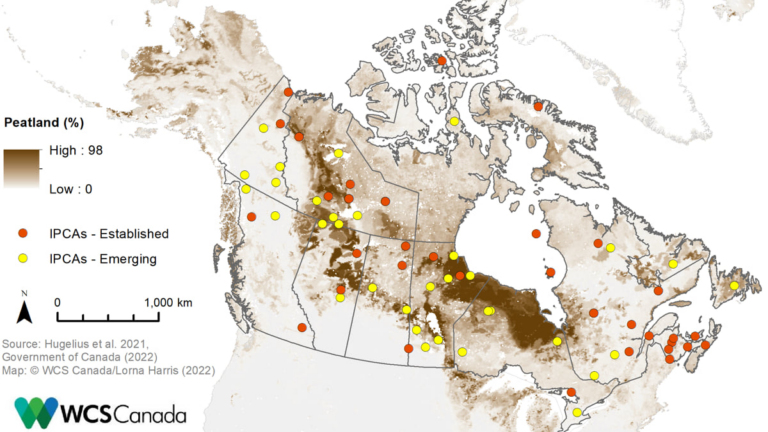

Indigenous peoples have been the stewards of the vast peatland landscapes across Canada from time immemorial and are working to establish research and community-based monitoring programs to continue this work. Peatlands across Canada are part of cultural landscapes of importance to many First Nations. In recognition of this essential connection, there’s a push to expand Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) across Canada’s northern peatlands.

Peatland destruction causes the loss of carbon and takes away the future carbon absorbing capacity. It turns the world’s best carbon sink into a carbon source. And peatlands can’t rebound like forests.

“We can’t re-create peatlands,” Harris said. “You can restore them, but you often get something completely different, and you can’t recover the lost carbon. Peatlands have taken thousands of years to absorb all that carbon and build it up. Even if you give it 10, 20, 30 years, that’s nothing in the lifetime of a peatland.”

Canada’s peatlands can keep that carbon stored for many thousands of years. That’s much longer than other carbon sinks, such as rainforests, which can release carbon relatively quickly—over decades and centuries.

WCS Canada’s goal is to work with partners in the Hudson Bay Lowlands to track changes as they happen, including mining activities, permafrost thaw, and wildfire damage. The data collection will give a clearer idea of what’s happening across Canada’s peatlands, an area too vast for achieving comprehensive ground truth.

Building this knowledge is a challenge; the areas are distant and secluded. “There aren’t research stations,” Harris said. “The only settlement is small communities, hunting camps, mining camps.”

Even maintaining a charged battery for a computer, tablet or mobile phone is nearly impossible. “It’s a very difficult place to work,” Harris said. “It’s swarming with bugs most of the time, blackflies and mosquitoes, so we’re all in the peat bog with our bug jackets, sealing up any gaps so they can’t get through.”

The expense of reaching these remote regions is high. The annual cost of using a helicopter to cover even a small lowland area starts at $60,000. “That makes it very challenging to get baseline data, do the monitoring, and get back,” Harris said.

WCS Canada is working with partners to set up remote monitoring, using sensors and satellites to learn more about peatlands across Canada and make the most of the organization’s limited budget. WCS Canada plans to expand its use of technology to track peatlands, including the use of drones, aerial imagery, and lidar data.

“We’re determining what’s going on in each area based on the data we have available,” said Meg Southee, lead geospatial data analyst at WCS Canada. “We’re using remotely sensed data, and we’re modeling based on that.”

Canada still has a long way to go to protect the vulnerable forests and peatlands of the boreal region. “I’m currently looking at oil sands expansion in northern Alberta, and a fen [a type of peatland] that’s taken close to 8,000 years to develop and could be destroyed in an instant,” Harris said. “Some restoration would be possible with a lot of work, but you can’t get back these landscapes that are thousands of years old.”

In WCS Canada’s recent policy brief on protecting northern peatlands, GIS-driven opportunities for conservation action are described, including developing a complete inventory of current peatlands and potential dangers. This effort to enhance the mapping and monitoring would include tracking relevant industrial activity to develop a full picture of what’s happening to the peatlands, and where.

With the current wildfires, Canada’s vulnerability to climate change is at the forefront. WCS Canada is working with global partners to get peatland conservation on the global climate action agenda to free up funds to tackle this important challenge.

“The United Nations Environment Programme has been working to bring all the major peatland countries together,” Harris said. “Peatlands only cover about 3 percent of earth’s land surface, but they store nearly 30 percent of the total soil carbon. It’s a very small area relative to forests, but they store more carbon than all the world’s forests combined.”

Learn more about how maps inform intelligent conservation efforts.