I came back to the public sector because it’s where the most work is needed. It’s where you can solve the most important problems.

June 3, 2020

When California Governor Gavin Newsom issued the state’s first stay-at-home order in March, Maria MacGunigal faced a dilemma. MacGunigal, chief information officer for the City of Sacramento, had spent months leading an overhaul of the local 311 customer service system. She and her team were just adding finishing touches.

In response to COVID-19, MacGunigal had to decide whether to postpone the re-launch until everybody involved was back in the office or attempt the delicate task of making the shift while everybody was sheltering in their respective places.

Overhauling a city government program—especially one designed to connect residents with municipal services—is an intricate proposition in the best of times. In the middle of a pandemic, the success of that transition is crucial.

Sacramento is primarily known for being the home of California’s statehouse. Those who live in the capital city know it as a thriving community in its own right. Located in the agriculturally rich Central Valley, Sacramento is a quintessentially American crossroads—the country’s fourth most ethnically diverse city, by one recent reckoning.

Sacramento’s 311 system, first launched in 2008, logs around 500,000 interactions each year—or one for every Sacramento resident, a high level of engagement.

I came back to the public sector because it’s where the most work is needed. It’s where you can solve the most important problems.

Soon after MacGunigal took the CIO job in 2013, 311 came under her purview. “That isn’t typical for a city’s IT department,” she says. “But the 311 system was struggling under heavy demand. So the whole unit was assigned to me to revamp the call center from an operational standpoint, and also to provide it with appropriate technology.”

Much of the challenge involved the unusually ambitious scope of Sacramento’s 311. Although most major cities have a 311 service where people can call or go online to report problems or learn how to contact municipal agencies, the majority structure 311 as an adjunct city service. In most models, 311 has a primarily ombudsman role.

Sacramento’s 311 is more like a connective tissue—”the front door to Sacramento,” as MacGunigal puts it, “the highest touchpoint for all the interactions the city has with the community.”

Besides linking Sacramento residents with city services, 311 also serves as an internal hub linking many city departments. If somebody uses Sacramento’s 311 to report a stray dog, for instance, 311 logs the call and routes it through a system that sends a notification for animal control officers in the area. It also generates a ticket that provides automatic updates on the status of the problem.

“Most cities don’t have that kind of back-end integration through all those business lines,” she explains. “It doesn’t have nearly as much of an impact on the community if we’re just taking notes and handing off the requests.”

MacGunigal grew up in Southern California’s Riverside County, at the midway point between Los Angeles and Palm Desert, California. While attending college in Sacramento, she worked as an intern at the city’s Department of Information Technology, which she now leads. With a few brief detours into the private sector, MacGunigal has spent most of her career in that department.

“I’m a super-corny nerdy kind of person,” she says. “I believe fundamentally in public service. I came back to the public sector because it’s where the most work is needed. It’s where you can solve the most important problems. To impact more than a thousand people in a city in one day is very gratifying.”

MacGunigal studied geography in college, fascinated by how the subject touched on nearly every other discipline. It led her to become adept at geographic information systems (GIS), software that gathers, processes, and displays spatial data on digital maps.

When she was tasked with leading Sacramento’s 311 overhaul effort, MacGunigal had two major objectives. She wanted to broaden the program’s scope even further, to eventually become “a foundation upon which we can build all other portal access to the public.” And, she wanted to use GIS to improve the system’s real-time interface.

“Geography—the spatial relationships between things—is the easiest way to convey these kinds of complex data to people,” she says. “Having GIS embedded in 311 is really important to improve the average citizen’s experience.”

“From a technical perspective, 311 has always had a strong integration with GIS in Sacramento,” says Dara O’Beirne, Sacramento’s GIS developer. In the past, he explains, GIS was mainly used as part of the 311 system’s backend, rather than its user interface.

The new City of Sacramento 311 Customer Service Help Center website and mobile app setup accomplishes both objectives. Salesforce customer relationship management software (CRM) connects to a server running ArcGIS, the GIS software platform engineered by Esri.

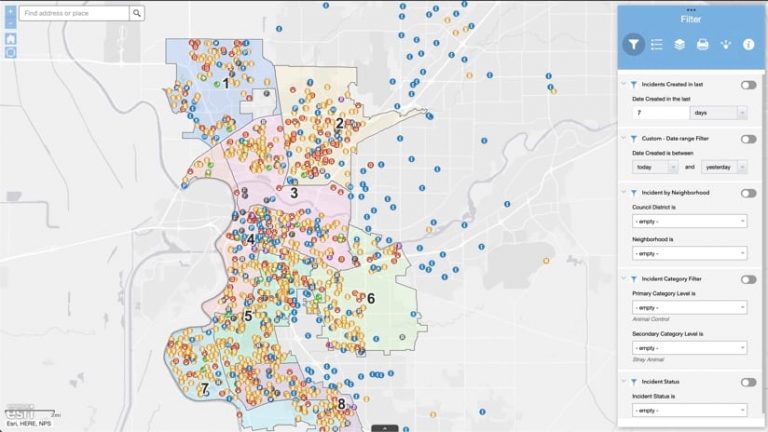

When a community member submits a 311 ticket, the GIS component first verifies the user’s issue pertains to an address within the Sacramento city limits. It then situates the location relative to 35 different map layers. “Like, for example, what council district is it in?” O’Beirne says. “What’s the animal control district, or the police district, or even the police beat? All these values get pulled in from just one address entered into the system.”

For the 311 site, Salesforce integrates with GIS maps provided by Esri’s cloud-based software. “We now have data from GIS maps and layers, and we take the Salesforce data and start building dashboards around it,” explains Ivan Castellanos, Sacramento’s 311 manager. “There’s even more value in the data now because it can be used to help various City departments drive their strategies and make data-driven decisions.”

As MacGunigal and her colleagues absorbed the reality of sheltering in place, the issue of full 311 implementation loomed large. With something as public-facing as 311, initial impressions are key. After all the work they’d put in, was the effort to push the project over the finish line while the team was scattered worth jeopardizing it?

After some hectic video-conference meetings, the team decided to forge ahead. Sacramento’s new 311 debuted April 15, a mere month behind schedule. All feedback suggested any hiccups, inevitable in this kind of launch, were minor.

The changeover also required surmounting a new hurdle. Operators trained to answer calls in the 311 call center were among city employees who had been sent home. In addition to launching the new system remotely, the team also had to figure out how to make the 311 call center function remotely.

“It’s not unheard of in the private sector to have call centers that have a lot of distributed locations, whether that’s at people’s homes or just multiple locations for call-taking, but we’re one of the first public agencies to have a mostly remote call center,” MacGunigal says. “Everyone was remote—the development team, the GIS team, the infrastructure team—and we pulled it off without a hitch. So that was pretty awesome.”

Discover the many ways that cities use GIS to improve local government operations and enhance public services.