October 17, 2023

A vast, lush grassland stretches to the horizon in Argentina’s Iberá National Park. The gate of a large chain-link enclosure opens, and a jaguar wearing a GPS collar strides into the wilderness for the first time, leading her two cubs. In a nearby office, people beam at the unfolding scene, watching camera feeds from all angles around the jaguar reintroduction center. The release marks another remarkable milestone in Rewilding Argentina’s ambitious effort to repopulate the jaguar—something experts said was impossible.

“This is the first-time jaguars have been reintroduced anywhere,” said Carlos De Angelo, a professor, jaguar researcher at Proyecto Yaguareté (CeIBA-CONICET), and the project’s geographic information system (GIS) technology adviser. “It was an enormous effort.”

The largest cats in the Americas and a keystone species, jaguars were declared locally extinct in Argentina’s Corrientes province more than 70 years ago. Now, Rewilding Argentina is relocating captive jaguars, getting them acclimated to living in the wild, and releasing them to resume their natural roles in Iberá. De Angelo advised researchers on using GIS-powered maps and analysis to track jaguar movements and measure their impact on the ecosystem.

Together, Iberá National Park and Iberá Provincial Park form the largest protected area in the country. The parks are home to 4,000 plant species and a diversity of birds, reptiles, amphibians, and mammals.

Part of the legacy of Tompkins Conservation and its mission to protect and rewild the earth, Rewilding Argentina has reintroduced anteaters , pampas deer, red and green macaws, and peccaries since its founding in 2010. Tapirs and the giant otter will be reintroduced soon. Each time, GIS has been critical to the process. The technology provides a snapshot of the ecosystem before species are released, then it supports monitoring of distribution, behavior, and interactions once the animals are in the wild.

Adding the jaguar—the region’s top predator—required a deep understanding of the area’s complex ecological systems. The team relied on GIS technology to help answer essential questions: Where should the jaguars live? Will they be able to hunt natural prey? How many jaguars can the park support?

De Angelo and his team began by monitoring other animal populations. By inspecting predator-prey relationships, they saw patterns critical to ecosystem health and stability. The researchers also mapped numbers and locations of marsh deer, capybaras, and other prey to determine suitable jaguar habitats.

The first jaguars were released into the park in 2021. Leading up to their release, De Angelo collected jaguar data from the Pantanal, a similar wetland ecosystem in Brazil, to model ideal habitats and predict behavior.

Rewilding researchers use this data as a baseline to draw comparisons and insights about jaguars released in Iberá National Park. They take mobile devices into the field to record information and images with GIS apps such as ArcGIS Survey123, ArcGIS QuickCapture, and ArcGIS Field Maps. The collected data syncs to the team’s GIS database and populates interactive maps. Researchers then use GIS analysis to understand and monitor jaguar interactions with prey, vegetation, and other animals.

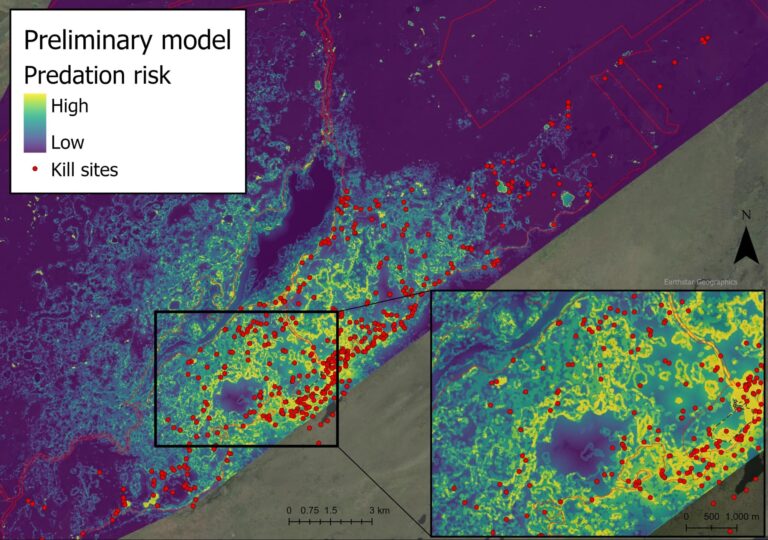

De Angelo leveraged this data to create a risk map for capybaras, the jaguars’ main source of food. Capybaras had been living in Iberá without a predator for decades. What used to be a place for them to freely forage, relax, and sleep is now an area where they need to be strategic amid a predatory threat.

Drone imagery syncs to GIS maps, giving the research team a bird’s-eye view. When the map shows capybaras clustered together—a behavior adopted to protect themselves—the team knows that’s an area where they feel threatened.

This approach delivers a holistic understanding of the jaguars’ impact. “This risk map will help us understand how the capybaras are perceiving risks and how they may change their behavior. That will change the shape of these areas because they will stop eating there and then eat more in other places,” De Angelo said.

To complement inputs collected with drones and mobile apps, researchers set up a variety of camera traps across the park. These cameras collect valuable data about the animals that don’t wear GPS devices. When an animal wanders into a camera’s field of vision, the movement is recorded and can be analyzed with GIS.

“We are using all these technologies to make the process very quick,” De Angelo said. “Every 20 days or so, we analyze everything. We go into the field to corroborate the number of animals that were the prey of the jaguars. This is useful for two main things—knowing that reintroduced jaguars are doing well and understanding their impact and role on the Iberá ecosystem.”

Eleven years into the jaguar project, Rewilding Argentina staff are seeing its benefits. Local pride rooted in a reverence for nature has blossomed along with a robust ecotourism industry in communities along the Iberá National Park perimeter.

“Jaguars are a very charismatic species that are good for tourism. A new economy has been built surrounding the local traditions and the conservation of nature,” De Angelo said.

For centuries in South America, Jaguars were widely respected and viewed as icons of godlike power. Now, according to Diana Frete, the vice mayor of the nearby town of Colonia Carlos Pellegrini, these mighty felines are “symbols of living culture.” Residents have respect for and take pride in the nature of the region. Young people are more likely to stay in their hometowns and participate in the local economy by becoming guides and artisans.

Rewilding Argentina staff members will continue to monitor the surrounding environment, ensuring it will thrive. They are already using GIS to track invasive species, such as feral pigs and deer. Gauchos (cowboys) have been enlisted to keep an eye out for the animals, recording sightings with QuickCapture. That data feeds into the team’s GIS dashboard.

Jaguars have begun to have cubs in the wild. As the jaguar population grows, there is hope that their presence will naturally balance the Iberá ecosystem. A similar project reintroduced gray wolves to Yellowstone National Park and had cascading ecological effects. As the wolves preyed on the overpopulation of elk, which had overgrazed the land and eroded riverbanks, other species—bears, pollinators, birds, and fish—returned to their natural habitats.

In Iberá, jaguars prey on medium-sized predators that have freely hunted birds, lizards, and rodents for decades. De Angelo and his team hypothesize that, as the medium-sized predator population returns to its natural size, smaller animals, such as endangered bird species, will be saved from extinction.

With GIS technology, De Angelo can manage an expansive conservation effort. By adopting a combination of GIS mobile applications and dashboards, “Rewilding Argentina has the power to do more dynamic work,” he said.

Watching the jaguar project unfold has been a rewarding process for De Angelo. He remembers the first conversations about it in 2005: “When the idea was presented, everybody was saying, ‘Yeah, sounds nice, but it’s almost impossible.’ More than 15 years later, now jaguars are there. And the process is working.”

Learn more about how GIS helps preserve biodiversity and achieve sustainable conservation.