October 20, 2022

Researchers who study climate change impact—from rising temperatures and sea levels to dwindling biodiversity and new migration patterns—share a common problem: They are expected to investigate a phenomenon in person before they can speak with authority. But advances in technology are altering this bias towards in-person fieldwork.

Leaps in the precision and coverage of satellite imagery plus abundant on-the-ground sensors, location-aware 3D models, virtual reality, and modern geographic information system (GIS) technology to collect and map the data are working together to enable evidence-based research from afar.

This approach provides new vantage points—the ability to analyze across space and time at varying scales as well as time and cost savings—offering researchers a solid alternative to “going there.” The effects of travel on the environment and the need to be inclusive in research are other weighty factors being considered.

“Not going there” is such a big topic that The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) (RGS-IBG) in the United Kingdom adopted new principles for fieldwork that include guidance to consider carbon footprints and equality. The goal isn’t to do away with first-person observations, as leaders at RGS-IBG believe field experience is fundamental to geographic education. Instead, the RGS-IBG lays out ideas for balancing the needs of students and the planet.

At the same time, satellite images and sensors allow for remote monitoring under all conditions, whether indoors, outside, or at locations too hazardous to visit. Sensors also capture activity that would otherwise escape human sight or perception.

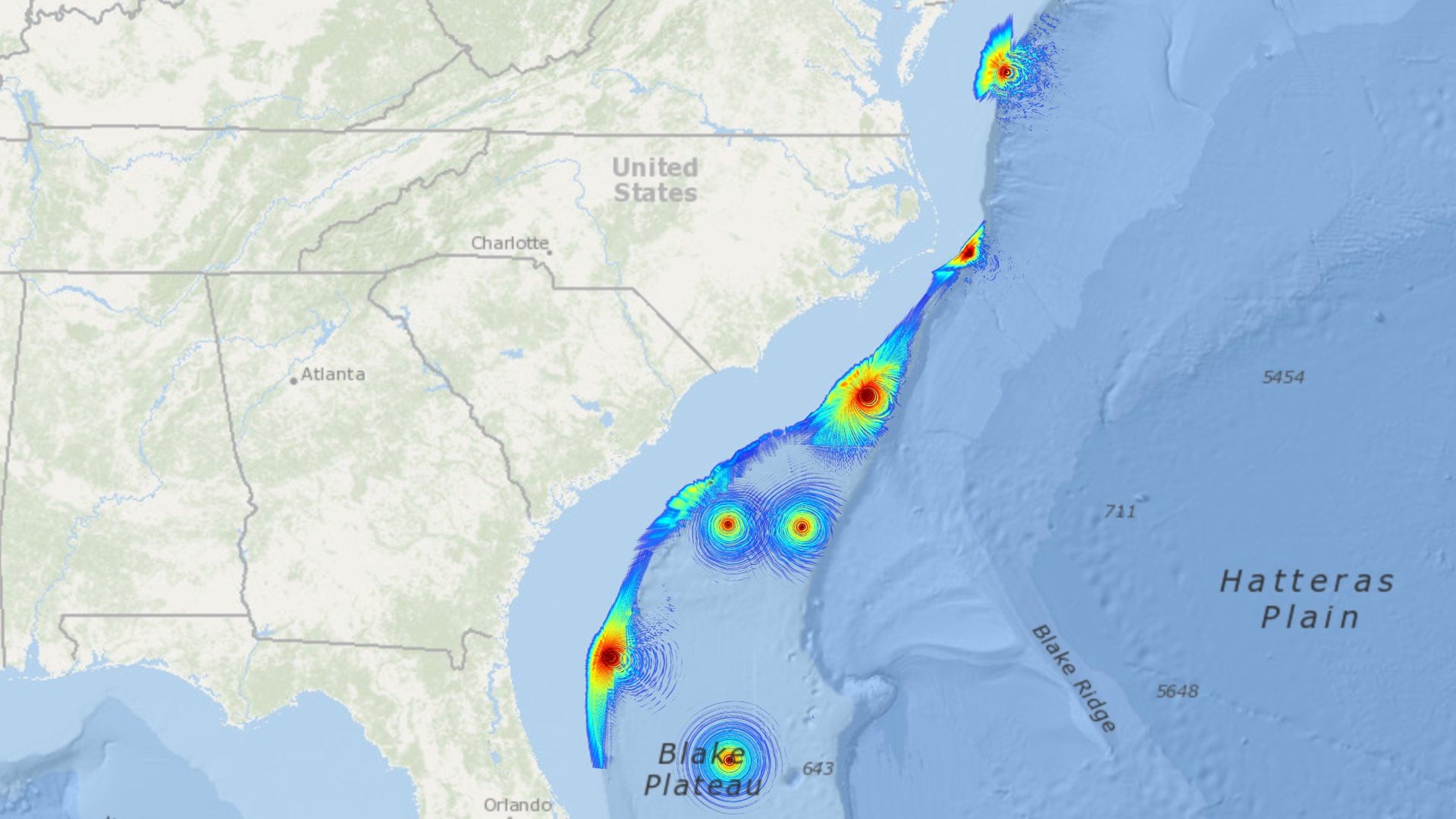

Layers of satellite and sensor data can be viewed and analyzed in the context of a specific location via GIS maps and dashboards. Using GIS to tap into these steady data streams allows for a level of analysis and insights well beyond what could be observed in the field.

A technology-forward approach to field research also expands the pool of researchers who can help move science forward. For people with disabilities or without financial resources, technology makes scientific investigation more accessible.

“As we recognize the privilege that enables such fieldwork—whether based on finances, reproductive and caring status, health status, levels of employment, or being concerned about one’s carbon footprint—we might elevate alternatives that negate the importance of those privileges,” wrote University of Notre Dame anthropology professor Susan Blum in“Fieldwork From Afar.”

Anna Guasco, a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge, pushed back on expectations for fieldwork in her studies as she dealt with chronic illness and limited mobility. She wants to see institutional change that moves fieldwork from its central position in geography.

“Fieldwork should have to be justified in the same way that not doing fieldwork is expected to be justified,” Guasco wrote in The Geographical Journal.

The scale and pace of global shifts make it more difficult for researchers to get a first-hand account of how places of interest are evolving. They often need tools to discern where change is happening and how. The combination of satellite and sensor data fed into a GIS proves essential to remote monitoring.

For instance, researchers are remotely monitoring patterns in bird migration and shrinking elephant habitats in Africa. They are studying human movement due to climate pressures, including following the flow of people toward clean water and abundant food.

Remote monitoring also helps in observing at scale the health of the oceans, to see the die-off of coral reefs at a geographic scale impossible to survey through in-person research.

Scientists can now detect and quantify even slight changes in events such as volcanic activity, sea levels, average temperatures, and rainfall. Data-driven GIS analysis helps them connect what’s happening to the landscape in one region and the impact on species in another place—all from afar.

Building on the work of GIS maps and data is the dynamic 3D model known as a GIS-based digital twin.

One place this next-generation technology is being deployed is the 25,000-acre Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve in California, where the digital twin allows researchers in any location to explore, measure, document, study, and learn from California’s last coastal wilderness. Scientists have compiled 90 layers of data in GIS about the archaeology, wildlife, and vegetation of this place.

“There’s a real opportunity to develop a new model for conservation, using open science to establish legacy datasets that can be brought together with other data streams to create a true interdisciplinary collaborative effort,” said Mark Reynolds, director of the Point Conception Institute, which oversees the science and management at the preserve.

The work also involves big data analysis, with the aid of artificial intelligence to decode troves of camera trap and drone images and other large volumes of data from sensors that record measurements across the site.

Virtual reality (VR) experiences can also help fill research gaps, Bethanne Tobey, a lead instructional designer at North Carolina State University, said in “Field Research From Afar.” Tobey is using VR and 360 videos in field and lab instruction, particularly for students in online courses who are less likely to get field experience.

Tobey and her colleagues at the university’s Distance Education and Learning Technology Applications division are creating VR experiences from GIS web scenes for learning exercises. With VR, students can learn such things as how to use fire to clear fields, aimed at preventing more destructive wildfire fueled by climate-related drought.

Rather than compromising quality in research, many experts see technology as providing additional tools for understanding what is happening and where. The remote monitoring made possible by sensors, satellites, GIS, digital twins, and VR expands knowledge and understanding. It opens the field of research to all participants, ensuring that the best minds, near and far, can help tackle the impacts of climate change.

Learn more about geographic information science.