Suddenly we had this sensor that was so sensitive that she was picking up things that our other tools couldn’t see.

November 15, 2017

Interactive Maps and Traps That Talk Provide a Tactical Advantage

New Zealand has always been home to many unusual species of birds and lizards, but too many have steadily lost ground to human settlement and the mammals that humans introduced. Their plight has grown increasingly dire due to growing numbers of three predators—rats, stoats, and possums. At stake is the country’s biodiversity, including many unique animals, not least of which is the flightless Kiwi that serves as the nation’s symbol.

Already, more than 40 species have gone extinct. Seeing the expanding threat, the government of New Zealand has declared an ambitious goal of ridding the country of all three of these predators by 2050. On an island larger than Great Britain, that’s a bold objective and it will require advancements in science and technology to pull it off.

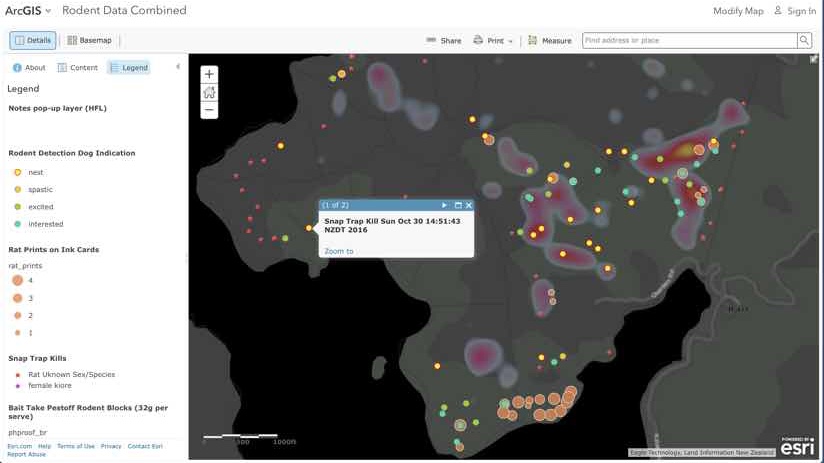

Experts from Ethos Environmental, a small conservation company that has been at the forefront of this fight, have taken a new tact that’s seeing great promise. They have deployed sensor-equipped traps, connected these sensors to a network, and then configured a geographic information system (GIS) to display real-time signals from the traps. When the traps catch something, the map lights up with the trap’s exact location.

“Up until now, the greatest number of traps any one person can check each day has been 50,” said Scott Sambell, manager of Ethos Environmental. “Now that we only have to check the traps that have caught something, a single person can manage thousands of traps.”

Living Laboratory

The government’s Predator Free 2050 program provides the overall framework and guidance for the ambitious plan. It invests in innovative predator control tools and techniques, and connects communities, businesses, philanthropists, scientists, and local governments who are making the vision happen.

Ethos Environmental gained a great deal of expertise on the problem of predators by working on a variety of different conservation contracts. The organization has also been hard at work bashing through the bush to eliminate rats from the Glenfern Sanctuary on Great Barrier Island.

The Glenfern Sanctuary is a 240-hectare parcel on a peninsula that has provided a testing ground for a variety of approaches. It is one of many private conservation efforts. A two-kilometer predator-proof fence was erected to cut off the peninsula in 2008, and then the hard work of ridding the predators within, and stopping anything from swimming around, began.

The sanctuary was started by the late Tony Bouzaid, a conservationist and legendary yachtsman, who had a vision to restore the land and to share the experience of native wildlife. The Sanctuary is the result of 20 years of hard work with over 10,000 native trees planted, an extensive trail network, and a swing bridge that allows visitors to climb into the crown of a 600-year-old kauri tree.

Ship rats eat the eggs of birds, and they multiply quickly. Stoats, a member of the weasel family, were brought into New Zealand to address a rabbit problem but have had a devastating impact on birds, reptiles and invertebrates. Possums eat an incredible amount of native bush every night, reducing bird habitat and food sources. Getting rid of these three predators will have a restorative impact on the forest, and leave a legacy for future generations.

“I’ve been setting traps and laying bait to try and capture the last rat, possum or stoat in the forest for years,” Sambell said. “Over time, I’ve realized how incredibly inefficient we have been.”

The conservationists tackling this country-wide problem work collaboratively and share what works. What has already become clear is that, for each species, a small number of traps is proving to be effective. Ethos Environmental helped to develop and test a SmartTrap system that is now manufactured and marketed by EcoNode, with Scott Sambell as co-founder. EcoNode makes sensors for each of the proven traps so that this remote sensing solution can be deployed to catch any animal.

Suddenly we had this sensor that was so sensitive that she was picking up things that our other tools couldn’t see.

Can Do

As residents of a remote island country, New Zealanders pride themselves on their ability to make do and innovate with the materials and solutions at hand.

“We have a term in New Zealand about the No. 8 wire methodology,” Sambell said. “All of the stock fences are made with No. 8 wire. If you break a fence, break a tractor, or something goes wrong, the saying is that any New Zealander can fix anything with No. 8 wire and a pair of pliers.”

The EcoNode team researched and deployed a wireless network, built a maker lab with electronic components and a 3D printer to create their sensor, and have harnessed the online software-as-a-service GIS platform ArcGIS Online to put their sensors on the map.

The ability to create maps, and apps, has been a force multiplier for both Ethos Environmental and EcoNode.

“I was in a meeting with the Glenfern trust board, and they expressed a wish to have an app to provide a self-guided tour of the sanctuary, because it’s hard to find tour guides and it’s expensive,” Sambell said. “While they were talking, I was writing the app, and I was able to show it to them online before the meeting was finished.”

Sensing to Control

At one point, workers at Ethos Environmental thought they had captured every rat in Glenfern Sanctuary; however, they were still seeing rat footprints on the ink cards in their tracking tunnels. This problem led to the first purchase of a sensor in the form of a specially trained conservation dog, Milly the Terrier.

“Suddenly we had this sensor that was so sensitive that she was picking up things that our other tools couldn’t see,” Sambell said. “It was kind of defeating.”

Milly’s sensitive nose helped the sanctuary rid itself of ship rats (rattus rattus), and she soon helped Sambell discover that they also had Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) on the property. While these are smaller rats with less of an impact, he decided to rid the sanctuary of these as well.

“It just blows people away when I can show them how many rats there are in the forest,” Sambell said. “Because I have a rat detecting dog, I know better than anyone how many rats there are, and their devastating effect on birds.”

Living Map

Glenfern Sanctuary has proven to be a very helpful laboratory to get a handle on the complexity of the predator problem. The work there has attracted many scientists who are finding the predator-free practices and species conservation efforts helpful for their research.

The sensors have the added benefit of providing excellent data on where, when and what has been caught. By making that data available, scientists are able to conduct analysis to learn additional details regarding predator behavior, which in turn helps advance New Zealand’s predator-free goal.

“Whatever we design has to be scalable,” Sambell said. “We’re not talking about Glenfern here or even Great Barrier Island, we’re always talking about all of New Zealand.”

One of the primary benefits of the live map is to make the problem real to all New Zealanders.

“A lot of people don’t get out in the bush,” Sambell said. “The average person looking at the live map will see the millions of rats moving throughout the forest across New Zealand and will understand what is happening.”

With GIS, the ‘Digital Earth’ vision is becoming a reality, and is driving community engagement, shared understanding, and collaboration at all levels of society.

View a story map about how Ethos Environmental has become smarter in solving the predator problem in New Zealand. Learn more about ArcGIS Online, the collaborative and flexible online GIS that forms the foundation of Ethos Environmental’s live trap-status map and community engagement.

The concept of a ‘Digital Earth’ has inspired citizens, scientists, policy-makers, academics and businesses from around the world to work toward creating a truly global network of systems to share information on issues critical to planet Earth. The concept of ‘Digital Earth’ is built on the idea that individuals, local communities, national, and international agencies can share environmental, scientific and spatial information seamlessly, freely and in near-real time. It’s only now, with developments in technology and geographic information systems (GIS), that many organizations, large and small, are organically creating that very ‘nervous system’ for the Earth. This three-part series highlights organizations in the Asia-Pacific region, from small environmental conservation groups in New Zealand to international agencies such as the United Nations, that are using spatial technology to realize this global vision of interconnectivity, collaboration and shared understanding.