January 12, 2021

When the Seven Pines Fire broke out in early November, it quickly consumed acres of scrub oak and mountain laurel along steep terrain near Swiftwater, Pennsylvania. Firefighters worked according to COVID-19 distancing needs and used live maps to concentrate containment efforts and protect homes. After four days, and with 812 acres burned, the human-caused blaze was out.

“This is 2020, so we’re managing the fire while we’re managing COVID-19,” said Shawn Turner, forest fire specialist supervisor in the Pocono Mountains for the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). “We couldn’t have a whole lot of people on the fire, because then we’d have to deal with increased exposure.”

The response effort included a regional team of firefighters and equipment such as a bulldozer to scrape the ground for fire breaks, a helicopter for targeted water drops, and reconnaissance aircraft to relay photos of the fire’s extent. Firefighters mobilized this response via a live map application called the Fire Mapper app, built with a geographic information system (GIS).

The Fire Mapper app let them see the work of others and report their own actions while keeping everyone away from each other because of the pandemic. It helped the teams orchestrate efforts as the fire and weather patterns changed moment by moment.

“We had very low humidity for two nights after the fire started,” Turner said. “This was in a remote area with dry conditions that hadn’t burned since the early 1970s, so the fuel load was high. We knew the fire could get large on us.”

Firefighters knew that if the fire crested a ridge beyond the state game lands where it originated, people in the 1,000 homes of the Pocono Farms East neighborhood would be forced to evacuate.

Fortunately, humidity increased, and the fire kept advancing in a northern direction, staying below the ridge and moving toward a more mature hardwoods section of forest with fuels that don’t burn as readily. “As soon as nighttime humidity recovered, like it normally does, it slowed the fire growth and gave us the time to get it,” Turner said.

Turner, who functions as an incident commander, has been enthusiastic about using Fire Mapper to guide field operations.

“When I started in 1990, we still used a compass to do surveying for wildfires,” Turner said. “We moved to GPS and GIS, but we still waited for a day or more to get a map out to the field. Now people are seeing what we can do with the live map.”

The Fire Mapper app was first created during the 2014 fire season by Matt Reed, operations and planning section chief for DCNR Division of Forest Fire Protection, with help from Chad Northcraft, a fire forester turned air tanker base manager. The two shared a vision for a live map that could help teams efficiently fight fires. Reed built an app using Esri’s ArcGIS Collector technology.

“There are four things that we’re constantly aware of in fighting fire that we call LCES—lookouts, communications, escape routes, and safety zones,” Reed said. “One of the first things we want to do is see where the fire is at and just pay attention. We always strive to have someone up in the air to relay information through the map.”

Fire mapping was used selectively during the first year, but it caught on and was rolled out statewide in 2015. Anyone involved in wildfire or prescribed fire activities within DCNR has access to the app so they can record their work.

“You know the saying, ‘a photo is worth a thousand words’? It is,” Turner said. “When somebody’s describing something to you, sometimes you’re not exactly sure what it is they’re talking about. But if they can take a photo and attach that to the map, then you get a really good idea of what’s happening.”

In 2016, dry conditions sparked 850 wildfires in Pennsylvania. In April of that year, the 16-Mile Fire burned 8,000 acres in the Pocono Mountains in northern Pennsylvania, requiring 130 firefighters who finally got it under control after two weeks.

“The 16-Mile Fire got very complex; it started as two fires that then came together,” Reed said. “Fire Mapper got a lot of use and a lot of exposure because we had people from all over the state responding to that one, and even people from outside the state.”

In 2020, five million acres across the western states of Washington, Oregon, and California were consumed by fires, including blazes that scorched more than 800,000 acres in California alone. The fires have been called climate fires because they reached farther and burned longer due to warmer and drier conditions.

Climate fires also threaten eastern US states, putting the 1.1 million acres of the Pinelands that span eastern Pennsylvania and western New Jersey at high risk. Recent droughts and dead trees from gypsy moth infestations have also heightened concerns for large fires in the Poconos.

Contrary to this year’s Seven Pines Fire, it’s not typical for a fire to burn for long or far in the Poconos in November. More than 80 percent of wildfires in Pennsylvania occur in March, April and May. It’s during those months when winds are higher and the sun hits the forest floor and dries out the leaf litter that conditions are the worst for wildfires. In 2020, dry conditions created an unusually high number of fires in February—161 compared to 11 a year earlier. Scientists expect ongoing shifting seasonal patterns due to climate change.

The region’s devastating 2016 fire season reinforced the need to invest in new fire lookout towers in the Poconos, replacing 16 towers built in the 1920s with new modern structures. While most states are shutting down and reducing fire towers, Pennsylvania has found lookouts to be cost-effective and superior to other monitoring methods in remote areas, so it’s building more.

“There are a lot of places where if people see smoke, they will get 10 calls to the 9-1-1 center,” Mike Kern, chief of the DCNR Division of Forest Fire Protection, told National Public Radio. “There’s other places in north-central Pennsylvania especially where no one will see a fire for a couple hours.”

The towers are a front-line defense to spot smoke quickly and keep fires small. The live Fire Mapper app collects all inputs and displays data for everybody, including key inputs from lookout towers.

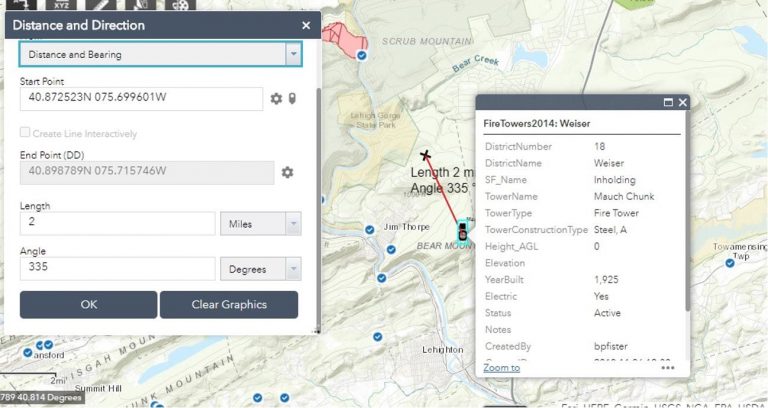

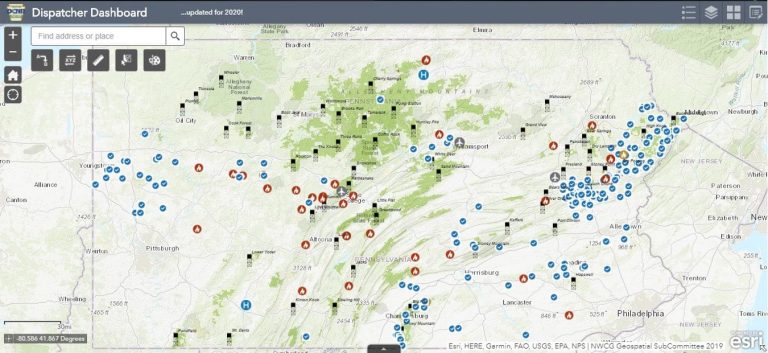

“I recently talked to one of our dispatchers who uses the tool in a district where towermen call in with the bearing and distance of smoke columns they see that she then pops on the map,” Reed said. “Next she sends the call out to see who she’s got in the field. I’m working on a dispatcher dashboard so she can see where her personnel are, see where the fire is, and dispatch the closest person automatically, sending them a location via the map.”

Yearly review sessions help Reed and his team hone the solution after each fire season and tailor it to meet the needs of more users. Despite the live map’s strong success over more than five years, some Pennsylvania fire districts have yet to adopt it.

“We seem to be battling the ‘that’s not the way we’ve always done it’ crowd,” said Chad Northcraft, incident management specialist and Mid-State Tanker Base manager at Pennsylvania DCNR. “Anybody that puts their hands on it sees the way we’re using it and its capabilities, and they’re immediately dialed in and know it’s the way to move forward.”

Fire Mapper spans a broad number of users who each view the map and use it for their own needs while contributing to the shared awareness of others.

“We have a recon plane in the air anytime it’s a fire day, and they’re up there mapping fires,” Northcraft said. “The more time I spend at the tanker base, the more I realize how the tool can be used in different ways.”

Incident management teams use Fire Mapper to track the location of firefighting assets, look at vulnerable properties and structures, and figure out how to access a fire. Leadership also shares the information to keep the governor and the public informed.

“I was on the Seven Pines Fire, but my supervisor was not,” Reed said. “He could just pull this right up on his screen and see what’s going on and give his report to the state forester.”

“It is important to have quick and accurate information when dealing with dynamic incidents such as wildfires,” said Ellen Shultzabarger, Pennsylvania’s state forester. “It’s beneficial to have this nearly real time data coming straight from the field for reporting and decision-making needs.”

Before calling in resources, on-the-ground response teams put a virtual pin on each fire, get an idea of each fire’s direction and how fast it’s spreading, and draw a polygon around the fire on the map.

For the Seven Pines Fire, the response team achieved a new level of awareness because a larger group of responders recorded their actions using a new tracking function.

“I couldn’t believe how simple it was to have the dozer boss mark his points,” Reed said. “We were able to just convert the dozer line to the controlled fire edge. We had another guy scouting to guide the dozer. It was so simple to say, ‘Hey, Greg, can you draw a line in where you’re proposing that dozer line?’ Greg says, ‘Yeah, here you go.’ And there it is on the map.”

Learn more about how GIS aids wildfire response.