January 16, 2025

In Pennsylvania, where roughly 1.5 million white-tailed deer roam, the hunting seasons running from September to January is based on firearm type.

Hunting is big in Pennsylvania. In fact, every Pennsylvanian has state game lands within a 20-minute drive of their home. The Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) manages the state’s 1.6 million acres open to the sport. Hunters can view interactive maps and dashboards on the PGC app or website to see when and where to hunt, state regulations, and how to report their harvests.

Staff at PGC keep this information accurate and widely available using geographic information system (GIS) technology. With GIS as part of its larger IT enterprise, data flows easily from apps to maps to dashboards.

“We used to just have a list of Wildlife Management Units (WMUs) and a black and white map,” said James Whitacre, GIS Services Division chief at PGC. “Now we have harvest dashboards for the four big game animals of deer, turkey, elk, and bear to keep track of what hunters are taking. We have a hunter notification map they can use to stay in touch with changes and plan their hunting and recreating.”

In addition to big game, the agency uses GIS to manage hunting zones and habitats for a long list of small game, furbearers, and migratory birds. It regulates different seasons for hunters using rifles, bows, traps, falcons, and muzzleloaders—a throwback to pilgrim times.

Hunters have a significant impact on the state’s economy with purchases of guns, ammunition, clothing, and other equipment. Hunting license fees and wildlife restoration grants fund the maintenance of healthy forests.

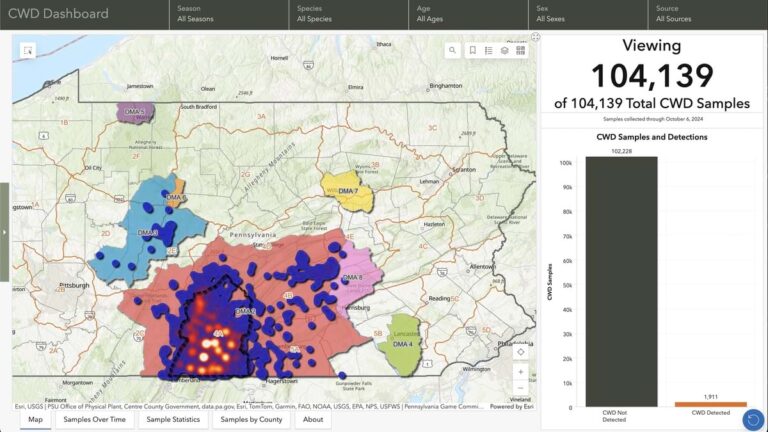

To keep wildlife and human activities in balance, PGC biologists analyze species numbers, hunting impacts, and disease mortality using GIS. The PGC also uses GIS to identify areas critical for conservation and to implement conservation plans and policies.

The PGC modernized its maps in the mid-2000s, examining research and statistics using GIS. They determined large-scale WMUs based on habitat and human-related land characteristics. Other considerations included human population density, public/private land ownership, recognizable physical features such as major roads and rivers, and land use practices such as agriculture, timber, and development.

The management units largely line up with habitat and species variability. The new system simplified areas to be monitored from as many as 67 units down to 21. This made it easier for hunters to access information and collect and analyze data for management recommendations. A constant flow of data helps the Game Commission guide periodic reviews of WMUs.

The PGC creates species-specific maps to guide where to hunt depending on what the agency is managing. For instance, hunters have 23 WMUs to choose from for deer—delineated based on deer population and the capacity of the land to support it. Deer thrive in Pennsylvania, and the state has the highest deer hunter density of any state, according to the National Deer Association.

PGC teams adjust management practices inside each WMU based on the latest knowledge about how animals behave, their lifecycles, and habitat conditions. As part of the modernization effort, they focus on creating one authoritative GIS dataset across the state that each region can edit in a central place.

“One of the reasons we always struggled with central data is that we’re a distributed workforce,” said Daniel Jones, GIS project manager at PGC. “We have six regional offices, 40 habitat crew offices across the state, lots of home offices, and biologists that are working in remote locations. So being able to tie all that data together into a central data source was always really a challenge for us, and it impacted data quality for decision-making.”

The shift to mobile devices and apps has helped accelerate data access and knowledge sharing. Statewide GIS services have consolidated local data to ensure transparency and awareness of trends.

For instance, the PGC combats invasive species and improves forest health with prescribed fires on nearly 20,000 acres of state game lands each year. GIS is integral to planning and implementation phases. Because this data originates in GIS, it can be easily transferred to apps for those conducting each burn and to the public.

Bird nest boxes provide another work-in-progress example. The PGC manages a network of more than a thousand across the state, placed in sites suitable for foraging by different species. Field crews added each box to the map to help ensure they are maintained and cleaned after each nesting season.

Nest boxes also act as a data collection point to monitor species’ health or improve distribution. The PGC added nest boxes for barn owls to reintroduce them to their natural range, and for American kestrels to monitor their health and declining population.

An app-based approach guides each foray into the field and informs an ecosystem-level awareness of how each species is faring.

“Getting tools into the hands of our field staff who know and can share the boots-on-the-ground information is critical,” Whitacre said. “It also aids researchers who are going out to make observations and do any sort of monitoring.”

While the PGC focuses primarily on bird and mammal species, staff work closely with other state agencies that also focus on conservation and the environment. The Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission manages fish, reptiles, and amphibians. The Department of Environmental Protection manages water quality.

The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources oversees habitats, with forest and parks divisions tasked with managing one of the largest public forest land expanses in the eastern US and more than 100 state parks.

The PGC takes on projects to support these other agencies. A recent project, the Aquatic Organism Passage program, converts a large number of culverts into bridges. Culverts work well to divert stormwater and keep roadways clear, but they cut off the movement of aquatic species. Bridges restore streams to their natural state and improve connectivity for fish and other aquatic animals.

“We put a lot of funding into that, even though fishing is outside of our realm, because it increases the overall value of that recreational space for hunting and fishing,” Whitacre said.

The PGC’s habitat crews are also involved in restoring lands reclaimed from old strip mines and other industrial activities.

“We use GIS to plan how to properly restore habitat,” Whitacre said. “We determine whether to rebuild a forest or create a grassland.”

When a deer population grows too large, they can overgraze an area and disrupt ecosystems. This happened in Scotland to the point where fences were needed, and trees and plants had to be reintroduced to the landscape. Hunting can prevent such problems.

“Hunting is a sustainable practice if it’s done correctly and managed well,” Whitacre said. “There are plenty of people in Pennsylvania who rely on a yearly harvest, and we rely on hunters to manage species numbers and their impacts.”

To encourage potential hunters and ensure the sport continues, organizations such as Backcountry Hunters & Anglers and the Ruffed Grouse Society have invested in marketing efforts.

“It’s a priority for us too to recruit the next generation of hunters,” Jones said. “Not only a younger generation, but a more diverse population of hunters, including women and minorities who historically weren’t involved in hunting. We have different mentored programs, going into the inner cities to get people involved in hunting.”

The state’s GIS app is helping, particularly for those who didn’t grow up hunting. On dashboards, hunters can see trends and learn where other hunters are succeeding. The app sends alerts to hunters about what to be on the lookout for and places to avoid—such as areas scheduled for prescribed burns.

“When the snow melts and the trees haven’t greened out yet is when we have an opportunity to burn. But that happens at the same time of year when hunters are trying to get out in the woods after being cabined up all winter,” Jones said. “With the hunter notification app, we can share where we’re going to burn so they can plan accordingly.”

Learn how conservation organizations use GIS to streamline natural resources management.