January 11, 2022

These are worrying times for the monarch butterfly. Droughts; climate change; pesticides; and the decline of milkweed, the plants on which caterpillars feed, have placed these important creatures in mortal peril.

Monarch numbers are down on all major migration routes. Monarchs migrating to coastal California plummeted by more than 99 percent in recent years, before experiencing a modest recovery this year, surprising scientists. The monarch also exists in regulatory limbo. On December 15, 2020, the US Fish and Wildlife Service determined that listing monarch butterflies under the Endangered Species Act is warranted, but has been delayed due to higher priorities.

Citizens and industry are taking action. Since 2015, a coalition called the Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group has been creatively employing mapping tools to rally energy and transportation partners—railroads, electric utilities, pipeline companies, state departments of transportation (DOTs)—to utilize long, narrow swaths of land to give the butterflies flight paths with the right plants to fuel their journey.

The Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group includes scientists, foresters, land managers, activists, attorneys, and educators who are fighting to save the monarch with a geographic approach.

Over the years, the group has engaged with conservation and natural resources agencies to foster best preservation practices alongside industry partners that have been building the business case, budgets, and collaborative action plans to improve pollinator habitat. The group has been growing its reach, partnering with more than 400 organizations across private and public sectors in the US and Canada.

The group’s plan involves linking butterfly travel corridors by connecting thousands of easements and other managed lands for purposes of transportation or energy generation or transmission. The total amount of energy and transportation lands available for habitat is unknown, but it’s estimated that there are roughly 17 million acres of land in the US next to state and interstate highways; 3 million acres of railroad rights-of-way; and 21 million acres of electric transmission and pipeline corridors.

“The insect apocalypse is going to have dramatic effects on our ecosystems, and our economy, and all sorts of interrelated issues,” said Iris Caldwell, program manager, Sustainable Landscapes at the Energy Resources Center, University of Illinois Chicago. “The vegetation managers, the folks out on the rights-of-way, take a lot of pride in creating habitat and providing positive benefits.”

The Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group combines map data from participating organizations using geographic information system (GIS) technology. In the Chicago region, habitat collaborators include the Illinois and Indiana departments of transportation, the Illinois Tollway, ComEd and NiSource (the regional utilities), and Nicor Gas (the area’s gas company).

“They all can see who’s doing habitat projects in which areas,” Caldwell said. “That helps them identify opportunities for collaborative projects—sharing capacity, resources, and hopefully having greater success.”

The Keller Science Action Center at the Field Museum in Chicago is a key technical partner that’s working on the geospatial database to visualize habitat areas along rights-of-ways throughout the US.

“Our current goal is for our rights-of-way partners to capture and maintain data for over 1 million acres of rights-of-way land that supports pollinators,” said Mark Johnston, lead GIS analyst and conservation ecologist at the Field Museum. “As the database grows, we’re now starting to see the role and collective benefits of these habitat areas.”

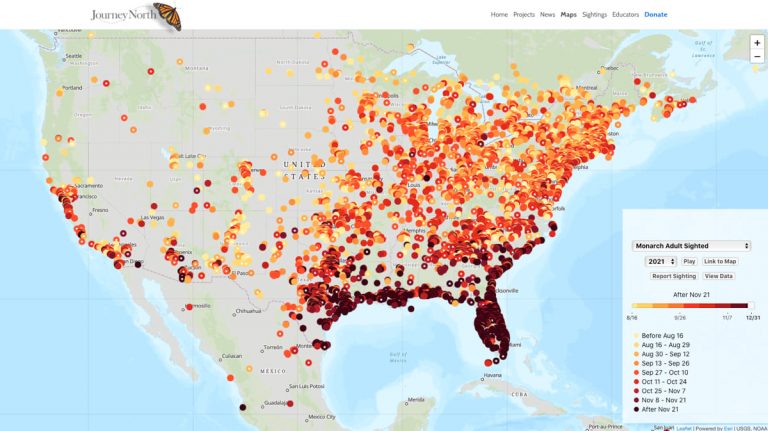

Every year, monarch butterflies undergo a northward journey that starts in the spring, moving from wintering grounds, mainly in Mexico. Three times along their route northward, monarchs lay eggs, and later caterpillars transform into butterflies. Then in the fall, a fourth “super generation” is born that makes the whole journey south again where they overwinter.

“The super generation lives longer and travels farther than the previous generations,” Caldwell said. “If it’s born in southern Canada, the journey could be close to 3,000 miles.”

This longest-journey generation gets a lot of attention and concern, because there are a lot of factors that lead to these monarchs’ success and survival. Climate change has become an increasing factor for the spring populations.

“When they’re heading north from overwintering in Mexico, they normally stop in Texas and lay their eggs there,” Johnston said. “In a warmer year, they go right past Texas, and it puts them up north too early when there isn’t enough milkweed yet, and a spring ice or snow storm can wipe out big portions of the population.”

It is estimated that five times more milkweed is needed to support existing monarch migrations. That’s why Johnston and colleagues conducted a study to document where milkweed exists and determine where more should be planted.

“Monarchs have to lay their eggs on milkweed because it’s the only plant the caterpillars will eat,” Johnston said. “Ideally, milkweed should be mixed with other native plants not only to provide additional nectar resources, but also to provide cover so the monarch caterpillars can keep hidden from predators.”

The milkweed habitat research led to the creation of GIS-based tools and planning guidance, which help cities and other landowners decide where to expand the planting of milkweed and other pollinator habitat measures.

“The idea of unmanaged nature is becoming less and less viable,” Caldwell said. “We have to intentionally create natural areas and take into account climate change to know where we are going to need this habitat 10, 20, and 30 years down the road.”

Proactive planting is part of future-proofing practices.

“Some land managers like to source their prairie seeds further south where plants are already tolerating hotter weather,” Johnston said. “That way, they’re getting plants that are a little more adapted already to an environment that’s getting hotter and hotter.”

The desire to improve pollinator habitat has caused many members of the Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group to reexamine vegetation management practices that are costly and labor-intensive. Regularly, utilities must survey and trim any trees that might fall on a transmission line during a high wind or ice storm, and railway and roadway managers similarly must provide a safeguard against trees and large shrubs that may halt mobility or block visibility. What many land managers are finding is that they can save money while improving wildlife habitat.

“Our members have begun applying the practices of integrated vegetation management, including the use of targeted herbicides, timed mowing, brush removal, and planting low-growing shrubs and broadleaf vegetation that outcompetes the trees that are problematic,” Caldwell said.

Up front, the cost of changing vegetation management practices may be higher, but studies are showing that cost savings accrue as the amount of tree trimming and other intensive vegetation management decreases over time. DOTs are also saving millions of dollars by just mowing a 10- to 30-foot swath of roadway, known as the safety zone, next to highways and leaving the rest of the roadsides and medians more natural. In Iowa, for instance, the Iowa Living Roadway Trust Fund is working to plant roadways with native prairie grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs, and has converted more than 50,000 acres to native habitat since 1990.

The Rights-of-Way as Habitat Working Group also instigated collaboration with the US Fish and Wildlife Service to help future-proof the members that are doing habitat restoration work. The group came together to develop a conservation agreement for the monarch that outlines the steps needed to adopt and document best management practices. Companies that take these conservation measures receive regulatory assurances that additional requirements won’t be mandated if the monarch is protected under the Endangered Species Act.

The agreement has already had more than 30 organizations apply that each make a substantial commitment to improving pollinator habitat. The Texas Department of Transportation alone has enrolled 450,000 habitat acres, and 10 other state DOTs have also enrolled in the program. Eighteen energy companies have made similar commitments, with more coming.

“This is a mechanism that rewards industry for voluntary conservation and also helps create and protects habitat on the ground,” Caldwell said.

Learn more about how GIS is applied to preserve biodiversity.