September 10, 2020

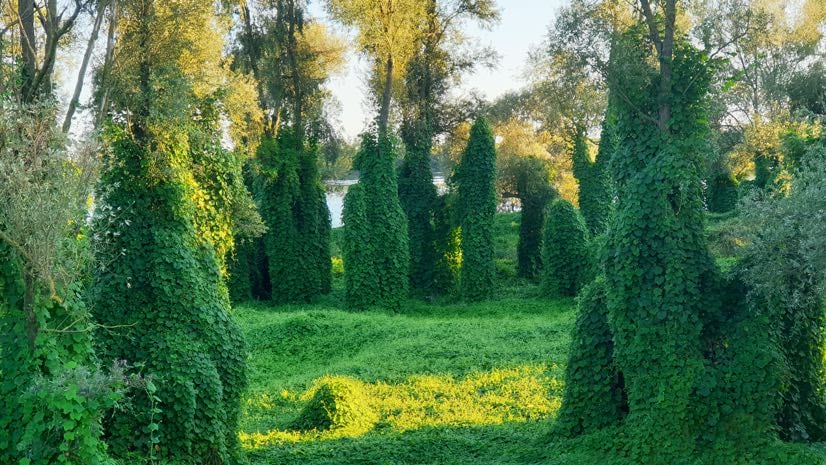

It was one of the stranger twists in an already strange summer. Across the country, thousands of people were receiving unsolicited parcels delivered by the US Postal Service. The parcels, which contained unlabeled packages of seeds, appeared to originate from China.

Federal authorities swiftly determined the packages to be part of a massive “brushing” scam. For many online retailers, an order delivered to a valid address is considered “verified,” regardless of whether the occupant placed the order. The sender can then post a positive review of the product that appears to be written by the recipient.

Although the scam easily revealed itself, there was still the problem of millions of unidentified seeds finding their way into the country with no safeguards. Some people planted them, more simply disposed of them, but quite a few turned to government agencies for guidance.

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS) office in Richmond, received the first reports on Thursday, July 23. By the end of that work week, VDACS counted 50 emails and 75 phone calls. Before staff went home for the weekend, VDACS released a statement to local media, urging Virginians who received the seeds not to plant them.

On the evening of Friday, July 24, a national news organization ran a story on the seed packages. The report named VDACS as a clearinghouse for information. Thus began the deluge. By the following Monday, VDACS had received 800 emails and the main office voicemail box was full.

“We got three days’ worth of people from every state in the country calling us to report that they had received unsolicited packages containing seeds,” said David Gianino, program manager for VDACS’ Office of Plant Industry Services. “We were getting overwhelmed with calls and emails.” By the end of the week, the three or four people who handle calls and emails for the office were struggling to get out from under over 2,500 responses.

One possible solution, an automated email response, had obvious shortcomings. Anyone making multiple reports would receive multiple responses containing the same information. It also wouldn’t be much of a timesaver for VDACS, since there are no easy ways to filter out data, especially regarding whether the sender was reporting from outside of Virginia.

Instead, Gianino and his colleagues used the automated response to direct respondents to a reporting form built on a geographic information system (GIS) online hub. The hub provided guided information for Virginians, instructing them on how to handle the seeds and how to file a report. The hub directed out-of-state residents to their respective agriculture agency.

Once the report was submitted, Virginia residents were instructed to send their packaging and seeds to the Plant Protection and Quarantine division of the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

“As soon as I saw what the reporting tool could do, I said this is what we need,” Gianino said. “We needed a form that people could fill out so our staff could receive the data in a way that helped them get caught up on handling the reports. The tool was what we hoped the reporting email could have been, but the email and its automatic response couldn’t tabulate data or location information.”

The GIS tool bought Gianino’s team some time. “As soon as we made the reporting form public, our staff could shift our efforts towards building a nice landing page or hub where the information could be laid out very consistently and cleanly,” he said.

When people reported their seeds, the landing page walked them through all the steps of reporting, securing the seeds, and sending them to the USDA.

“It provided our staff relief to pivot and say, ‘Okay, now we can take a break from answering phones and emails and focus on what our next steps are,’” Gianino said.

Beyond the immediate logistical relief, the online hub provided an optimal way for VDACS to analyze the unfolding situation. Recipients could even attach a photo of the seeds so the agency can begin to understand what these packages contain, and if there were any discernible patterns in the geographic distribution or in the types of seeds inside them.

With so little known about the seeds and their origins, it was difficult to tell how dangerous they might be. The seeds could contain pathogens such as boxwood blight, a destructive fungus, or they could be harboring invasive insects or noxious weeds.

“If imported seeds go through the right channels, they’re being declared and inspected,” Gianino said. “Authorities can then certify if the seeds are free of disease or insects.”

Whoever was sending the mystery seeds was not even declaring them as seeds, compounding the danger. “Not only do we not know what the plant is,” Gianino explained, “we don’t know if it’s safe to grow.”

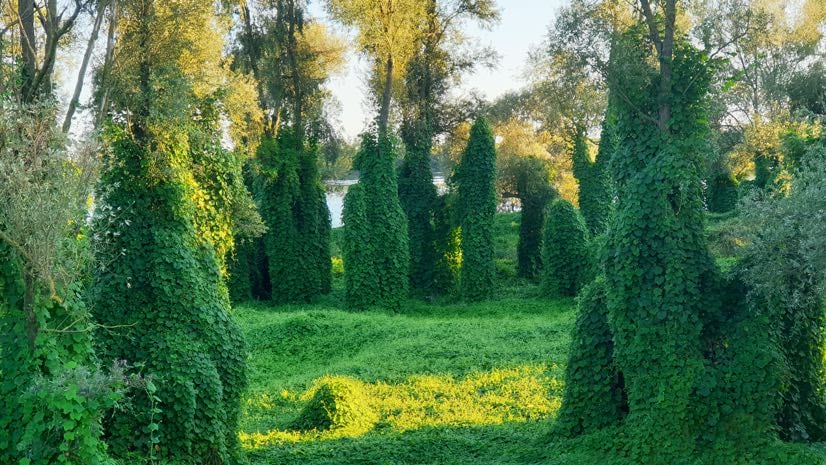

Even without diseases, the seeds posed dangers. Virginia has multiple protected areas with ecosystems vulnerable to non-native invasive plants. These plants could also potentially damage Virginia’s commercial farms.

Using its GIS program, Gianino’s team will be able to assess nearby problem areas when they receive reports of invasive plant issues possibly linked to the unsolicited seeds.

“Without a way to track where invasive plants become introduced, their spread can get out-of-control quickly,” Gianino said. “The more information we have up front, the better we can focus our response if any of these seeds are in fact invasive.”

If any of the seeds that were planted are invasive and they find their way into the environment, an idea of where they were planted will help the department identify locations for survey and control measures.

Gianino explained: “If someone calls to say they have a new and prolific vine growing all over their house now, and they planted these unsolicited seeds, our staff can look at the area and see if there are farms nearby, or a body of water we need to protect, so it doesn’t spread.”

Because all the reports will reside on the GIS hub, VDACS can get a head start on potential problems, even bringing the data into the field. “It’ll make us more efficient, and not just for handling reports,” Gianino said. “If inspectors need to collect survey data, they don’t have to take the data back to their computers and input the data at another time.”

Although the overwhelming reports of unsolicited seed packages have been disruptive to VDACS’ operations—and the seeds themselves pose a threat to state agriculture—Gianino took advantage of the dilemma.

“I used this isolated incident to identify our need for a reporting tool,” he said, noting the department now has a streamlined, long-term solution to handle resident reports and collect and report critical survey data. The hub and contributed data will help his team identify where future invasive species are coming from and where to focus their efforts.

And, Gianino finds another bright side to the whole mystery seed episode: “Some days I wake up and think ‘Oh my gosh, there are 180 more reports in the reporting tool,’ but those are 180 people that are at least paying attention and being engaged.”

See how other state and local government agencies are using GIS to engage and collaborate with communities.