September 1, 2022

A conservation group helped bring an Amazonian super fruit to market with sustainable practices—and it started with a map.

The buriti, known for its high concentration of nutrients, and its rich moisturizing and anti-inflammatory properties, grows atop 130-foot buriti palm (aka moriche palm) trees in the wetter regions of Brazil and Peru. Before Nature and Culture International (NCI) helped establish a formal and sustainable market for buriti, people would often cut down the palms to harvest the fruit. While this was apparently easier than climbing, the practice wasn’t sustainable because regrowth takes roughly 25 years.

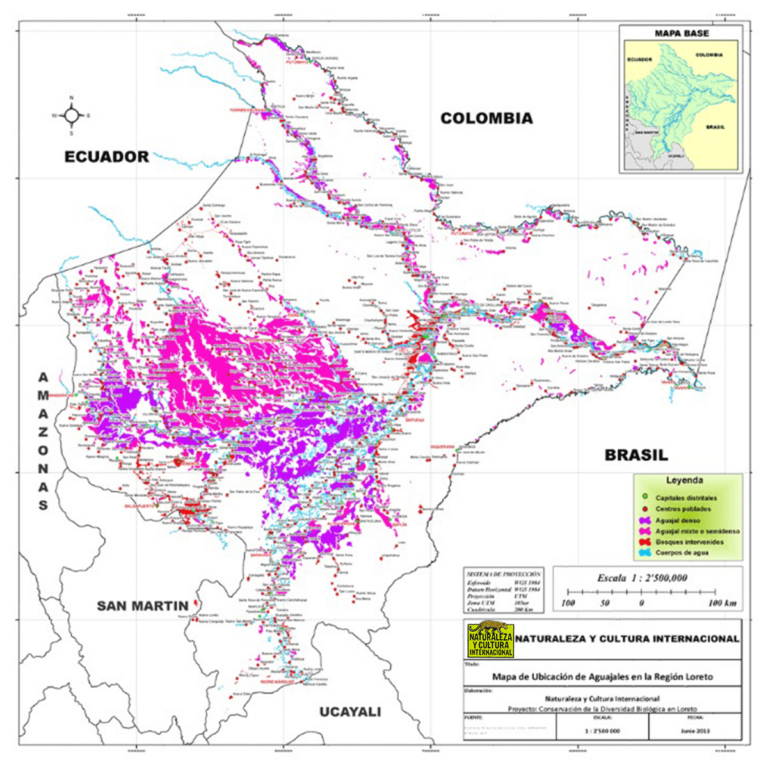

“We started this path of advocacy against practices that generate deforestation,” said Ricardo Rivera, NCI coordinator in Loreto, the region with the most buriti palm trees in Peru. The teams at NCI mapped 7.5 million acres of the Peruvian land near the Amazon, using a geographic information system (GIS) to specify the location and quantity of buriti palms and determine harvesting plans.

“We map the palm trees using satellite imagery and georeferencing,” Rivera said. “Then we transfer the information to many other stakeholders that we collaborate with.”

Aided by data-driven maps, NCI established a supply chain among local harvesters, government agencies, producers, and distributors to get the fruit sold in stores and sent to global markets. The GIS maps also guide strategies to preserve the native forests.

By combining income-generating plans with conservation efforts, NCI aims to set aside more acres of the Amazon forest for sustainable practices, with local knowledge enhancing the effort. Now, for instance, instead of cutting down the trees, local communities use climbing harnesses that they’ve modified for the purpose and for comfort.

Rivera, who works in the Loreto region of Peru where he is from, has a deep respect for the communities along the Amazon. He says that the Loreto city of Iquitos, known as the capital of the Peruvian area of the Amazon, “is the largest city in the world that doesn’t have a physical road connection. Instead, people and goods travel by rivers and planes.”

This isolation has aided conservation, with an estimated 95 percent of the region’s ecosystems intact. But it poses challenges to establishing a market for the super fruit and other sustainably harvested products from the forest.

“The communities around the forest are the owners of the forest. It’s very important to have them in this chain of value,” he said. “They protect the forest, and they are also improving their livelihoods.”

Due to the super fruit’s nutritional benefits and increasing availability, demand for products such as buriti oil has been growing. That exposure can create larger economic impact, leading to a perpetual cycle of what is known as productive conservation.

“It was hard at first, because we were not used to climbing the trees,” said Robert Rasma Marin, president of the Maquizapa Association from the community of San Antonio, Peru. “Instead of stumps where trees were once felled 20 years ago, the moriche palm trees have begun to repopulate the area again, and we’re managing our buriti better.”

Protecting the livelihoods of those who know the forest well is not only a fundamental imperative, but also essential to harvesting buriti fruit because of the labor force it takes to manage and understand the lifecycles of the tree and the ecosystems where they grow.

Harvesters benefit from GIS maps, using them to see the distribution of fruit and track where they have harvested. They also consult the maps when making decisions about where and how to collect, transport, and process the fruit at the point of peak ripeness.

Local communities also rely on their knowledge of lunar phases and the life-cycle of the fruit. They are mindful of factors such as weather shifts and market momentum, which necessitate stockpiling during times of abundance.

“The native people tell us that climate change and cold spells are a risk that we must notice,” Rivera said. “It’s very possible that this year the trees won’t produce the same amount of fruit as in other years.”

Companies benefit from NCI’s experience in sustainable harvesting with communities, which is central to the conservation-oriented nonprofit’s mission. For instance, one of NCI’s partners works with communities to transform the pulp of the fruit through freeze-drying, which makes it easy to store and transport without losing its nutritive value. This process reduces transportation costs and emissions, adding to the sustainability of the forest and the buriti fruit market.

“Our organization name is Nature and Culture,” Rivera said. “The culture relates to the community’s vision for the communities’ forest.”

Learn more about community-led conservation in a new book from Esri Press that highlights Jane Goodall’s work to empower local communities. Read more about how GIS supports sustainable conservation.