November 5, 2024

Louisiana is sinking into the sea. Or rather, the sea is engulfing Louisiana. Both are true; the combination of sea level rise, subsidence, and land degradation has claimed 2,000 square miles of coastline in the state. Since 1932, a landmass the size of Delaware has slipped under the Gulf of Mexico.

Following the brutal one-two punch of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, the State of Louisiana created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) and tasked it with safeguarding communities from the grim circumstances of rising waters. Projects include restoring barrier islands and marshes, constructing flood protection systems, and implementing coastal land-building techniques.

Tackling the big questions involved in land-loss mitigation is a responsibility that falls on CPRA’s team of coastal scientists, project managers, and engineers. The team includes Eric White, a research engineer specializing in hydrology projection models; and Rocky Wager, a senior coastal resources scientist with extensive geographic information systems (GIS) expertise. And the big questions include these: Where would be the safest locations to build the infrastructure? How much will it cost? What is the cost of inaction?

To predict the impact of rising sea levels on the Louisiana coast, CPRA has modeled potential coastlines 50 years into the future. Projections depict varying scenarios, each contingent on the completion of specific project proposals. The models help answer important questions: What does the coastline look like if the new levees aren’t built? How will building marshland impact the economy of this parish?

These models factor into the types of projects CPRA pursues. Decisions are codified in the Coastal Master Plan, which guides the work of the agency. The plan is updated every six years, most recently in 2023.

Projects are backed primarily by disaster relief funding, which means that the money to build tends to fluctuate based on catastrophic events. Following the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster, for example, about $15 billion in funding was made available from legal settlements, fines, and penalties, and $8.2 billion of that funding was dedicated to Louisiana. Every time a major storm hits—which has been about once every two or three years—the state receives finances to rebuild and harden the coastline.

“This idea of having a master plan is so that we are ready when funding becomes available,” White said from his office in Baton Rouge. “We’ve done this foundational work to set our priorities and do the initial triage of knowing what to go after.”

There are hundreds of potential projects that CPRA could create to lessen the effects of sea level rise, which is one of several tipping points the world’s coastal communities face. Strategies include nature-based solutions, such as marsh restoration, and hard infrastructure, such as levees and sea walls. Leveraging GIS applications, CPRA can effectively map historical, current, and future coastal conditions. This enables the testing of intervention scenarios within GIS, which assists in prioritizing efforts to vulnerable coastal areas. The adoption of model-based GIS approaches have proved to be successful, offering optimal solutions to address Louisiana’s worsening coastal crisis.

In Louisiana, community input plays a significant role in the plan framework. Concepts are solicited from the public and members of advisory groups to address key coastal concerns. These groups consist of local officials, community leaders, scientists, and residents who provide input on the challenges and priorities of their respective regions.

“All the complexities of our coast—the small waterways, bayous, ridges, and levee system—they could navigate it on a boat in the dark,” White said of community-led collaborators and their depth of knowledge. “Sometimes people mail in drawings of changes they want to see, or areas of concern.”

Digitizing and georeferencing proposals with GIS technology is often the first step of analysis. Then, CPRA uses geographic data to make cost projections. Land cover dictates the materials and structures the organization will build. Existing elevation determines the volume of material that is needed. Sediment density indicates the amount of dredging required. The distance between dredging sources and project areas impacts the project cost.

Sediment stabilizes coastal landscapes and protects them from flooding. Moving sediment to create marshlands is one of many nature-based solutions that CPRA employs. Marshes shield infrastructure from storm surge and provide many ecological benefits such as filtering pollutants and fostering biodiversity by creating healthy habitat.

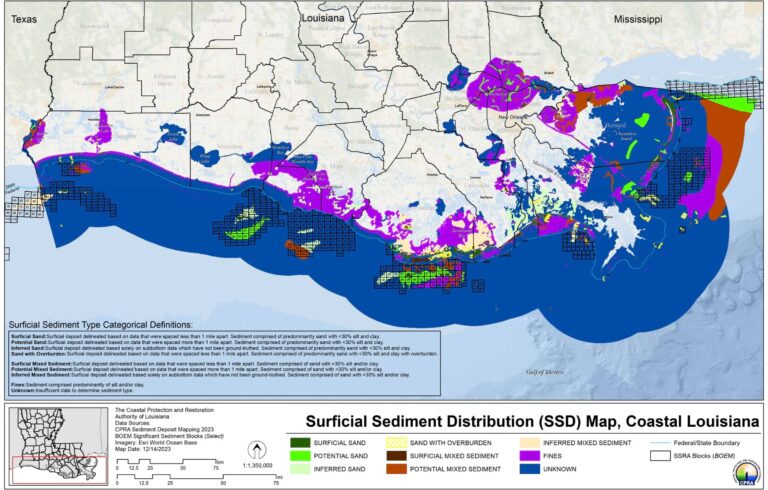

Much of the coastal restoration work involves moving sediment from one place to another. The process demands big-picture thinking and a high degree of precision to achieve the intended effects. The team uses GIS technology to determine how much sediment is needed for a project and where it will come from, and to track the logistics of transporting it from a borrow pit—where it is sourced—to the restoration site.

For this, CPRA relies on its sediment management team along with the GIS expertise of their internal and external partners that include the US Geological Survey (USGS). Wager and team work with USGS developers to manage the Coastal Information Management System (CIMS), which offers access to many Louisiana GIS datasets pertinent to coastal protection and restoration. Licensed surveyors and geologists routinely collect this geophysical exploration data to be included in the CIMS database. Side-scan sonar imaging and other survey data are collected to view 3D contours of project borrow pit areas. These images assist project teams with planning efforts and to help identify a suitable borrow pit sources.

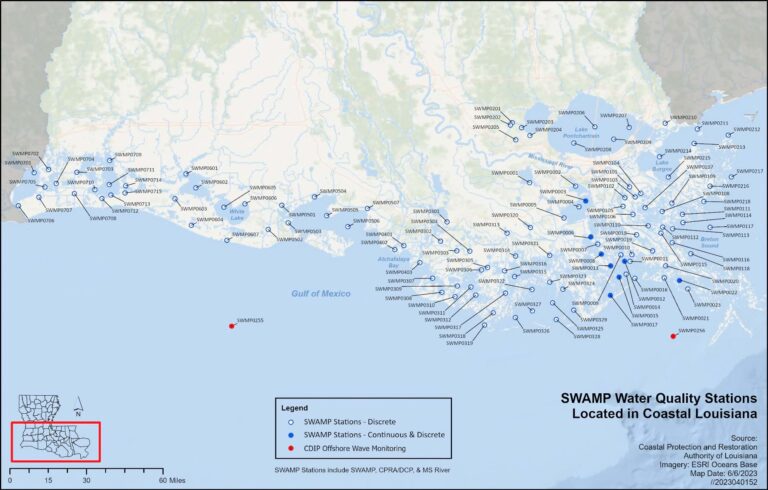

CPRA staff also continually monitor conditions at 391 stations along the Louisiana coast. This network, collectively known as the Coastal Reference Monitoring System (CRMS), keeps track of land-loss indicators like the direction of water flow, vegetation, soils, and land elevation.

Data from the field is uploaded to CIMS. For the sediment work, a custom web application created with ArcGIS facilitates the workflow. Data undergoes quality checks and is joined with basemap layers to show current conditions on a map and denote changes over time.

CPRA and USGS utilize GIS databases to store and manage spatial aspects of their projects. After data processing, the GIS data is ingested into the CIMS database so that it can be shared with planning and construction teams and project stakeholders. “This data is consistently used to develop cartographic products to inform project managers about suitable borrow pit areas and access routes, along with potential project obstructions such as oyster leases and oil and gas wells,” Wager said.

As projects become operational, CPRA staff monitor field data to gauge the impacts of the many resilience and restoration efforts. They watch closely for shoreline erosion, using lidar for detailed 3D maps that inform change analysis. In emergencies, CIMS enhances responsiveness of levee operators who use real-time water level data from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) buoys, US Army Corps of Engineers river gauges, CPRA’s hardened structure gauges, and USGS water gauges. This observational data is critical for emergency events, such a hurricanes and floods.

Numerical modeling has been the foundation of each master plan dating back to 2012. However, with a grant from the National Science Foundation, the 2023 update to the Coastal Master Plan leveraged the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center’s (PSC) immense computational power to build a time-lapse picture of the shoreline, showing projections for 10, 20, and 30 years into the future. These predictive maps help set clear expectations for community stakeholders.

“You can’t really write summaries of all of those dynamics in a succinct paragraph or even a one-pager,” White said. “To see on a map where you have risks being reduced—that’s a much more intuitive way to get our message out and let people explore it on their own.”

Promise and progress abound. Recent headlines describe how redirecting the Mississippi River will create a natural protective wetland for the Barataria Basin. Another controlled injection of river water will restore swamps along Interstate 10. Endangered sea turtles and pelicans have returned to wildlife refuge areas after a 75-year absence.

The situation is not without challenges. Sometimes debates over what to build can last decades. Coastal measures have the potential to disrupt ecosystems and the livelihoods of the people living and working there. The stakes are high.

The work of the CPRA walks the line between the past and the future, the known and the unknown. GIS maps and models paint a clearer picture of what that unknown might look like, helping build consensus and advance the right solutions.

Learn more about how GIS is applied to drive successful climate adaptation and mitigation measures.