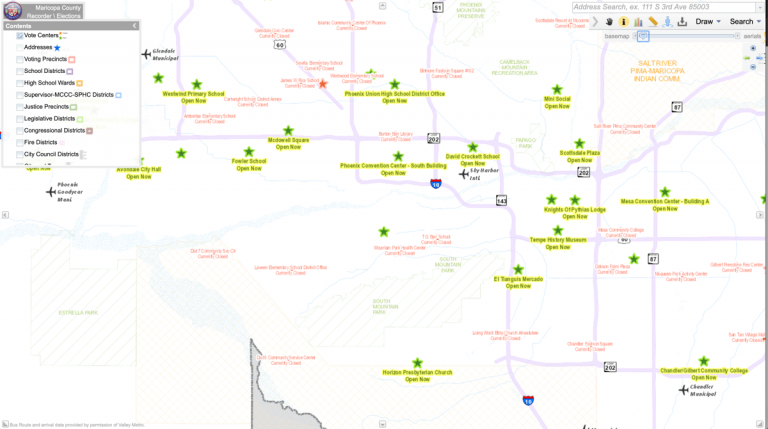

We can display them on the map, overlay them with heat maps [showing the location’s likely voters], and see where it made sense to put more locations.

July 30, 2020

During the two weeks leading up to Arizona’s Democratic presidential primary in March 2020, the daily tally of COVID-19 cases in the United States increased sevenfold. In Maricopa County, which includes most of the Phoenix metro area, officials were aware a storm was coming. They quickly shifted to implement new protections for voters and poll workers. Adding to the challenge, protective gear and cleaning supplies that were ordered had been diverted to California, leaving too small an amount for the recommended safety protocols.

Across the country, states with primary elections that month were faced with the same dilemma, as new cases ballooned from nearly zero to upwards of 25,000 every day. As the term physical distancing entered the lexicon, it was clear that voting, which attracts large crowds to centralized locations, needed an emergency reassessment.

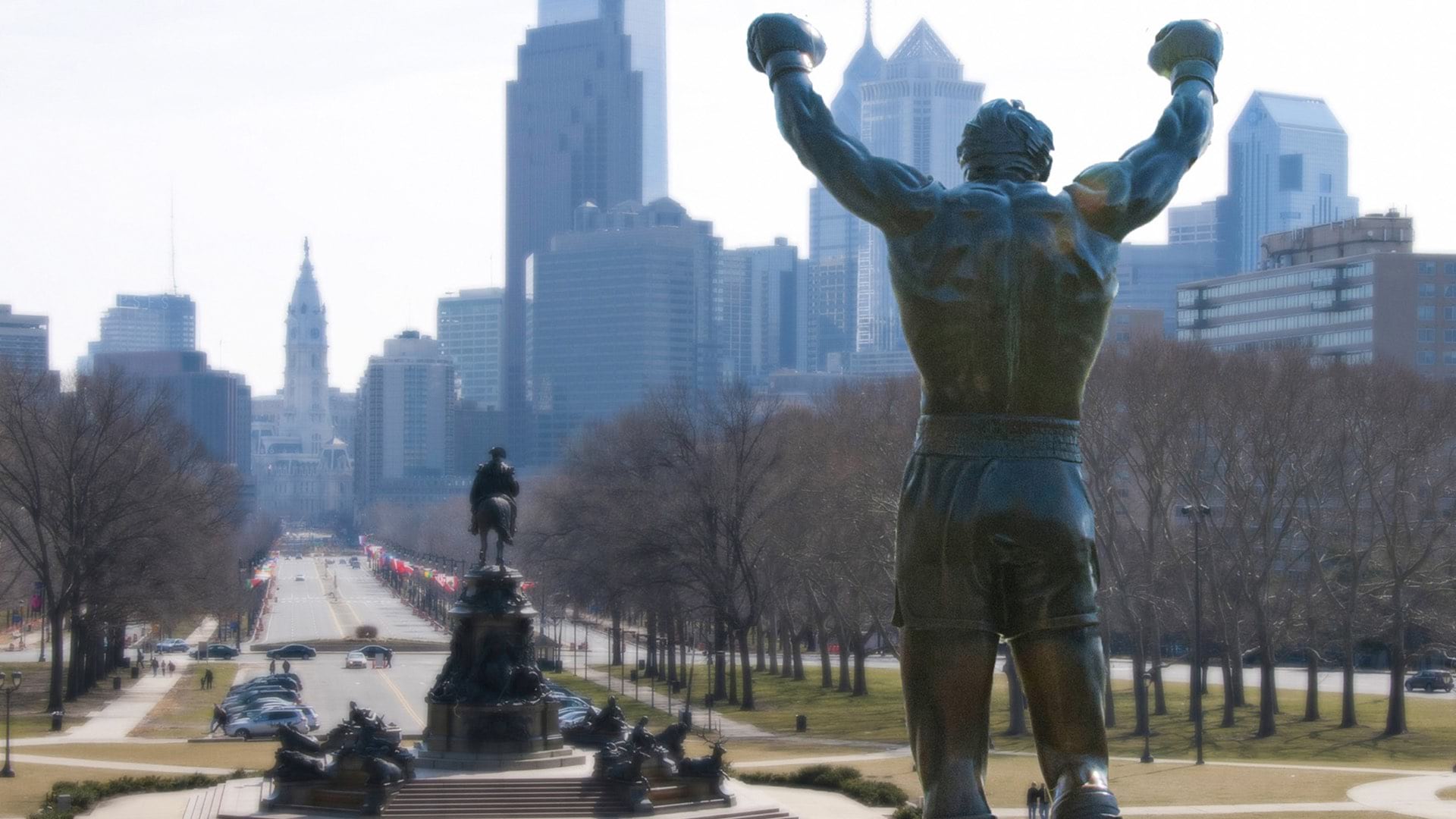

In Maricopa County, the logistical challenges were especially acute. Of the more than 3,000 counties in the US, Maricopa ranks fourth for population and fifteenth for size. Only California’s San Bernardino County has a comparably large combination of people and geographic area—and only California’s Los Angeles County has more registered voters.

Furthermore, Arizona has emerged as a solidly “purple” battleground state. The ability of Maricopa County’s voters to participate in free and fair elections during an historic pandemic carries consequences far beyond the Salt River Valley.

The majority of Maricopa County voters take advantage of the state’s robust mail-in ballot system. Although the March election was only for the county’s 800,000 registered Democrats, officials predicted around 100,000 would arrive at polling places to vote.

Many traditional polling locations were no longer viable. Senior centers were now closed, their clientele at severe risk for coronavirus infections. Any locations with spaces too cramped for adequate social distancing were also out. As the primary date approached, Maricopa officials engaged in an increasingly frantic attempt to close some locations and establish new ones.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis began, state law required Maricopa to consolidate polling places so that the total was half the number typically used in a general election. This was a meticulous process that considered in-person voting trends, population centers, and input from community advocacy groups. In 2016, Maricopa had garnered unwanted national attention after miscalculations forced voters to endure long lines at the polls.

In the years since, Maricopa election officials had begun to use smart maps, built with a geographic information system (GIS), to visualize the locations of likely voters and calculate travel times.

We can display them on the map, overlay them with heat maps [showing the location’s likely voters], and see where it made sense to put more locations.

For the March election, Maricopa County leaders were able to retool the system of in-person voting by moving to a Vote Center model, which allows voters to choose from any of the county’s polling locations. GIS allowed election officials to ensure equal access throughout the county, while also reducing the risk of further closures at schools and senior living facilities.

Faced with the public health emergency, election officials have found a new use for their GIS technology, as the county prepares for Arizona’s primary election in August.

“We’ve started acquiring space in places like strip malls,” said Gary Bilotta, director of IT and GIS for Maricopa County. “We can display them on the map, overlay them with heat maps [showing the location’s likely voters], and see where it made sense to put more locations.”

In modern elections, GIS is already common. For instance, voters use GIS web apps to find their legislative district based on their address.

But the most innovative uses of GIS for elections often occur on the back end, never glimpsed by voters. As the act of voting has itself becomes more political, with battles over the placement of polling stations erupting in states such as Georgia, Wisconsin, and Kentucky, municipalities are using GIS tools to ensure fairness.

“When we select a polling location, it’s not just ‘here’s a good building,’” said Carly Koppes, clerk and recorder for Weld County in northern Colorado. “It’s also ‘here’s a building, and here’s how many potential voters could use it.’ We integrate information on a map with overlays. We can even look and see how many people have used it in the past, and if it’s low, we can see if maybe it’s because there isn’t a lot of population density, or maybe it’s because of transportation.”

The process has helped Weld County find optimal locations for 16 ballot drop boxes for voters to use in lieu of polling stations, adding a layer of social distancing to the voting process.

In Utah County, in central Utah, officials use GIS to promote a shift away from in-person voting. “Because of COVID-19, we’re trying to get people to use mail-in ballots, instead of voting on Election Day,” said Andrea Befus, a GIS analyst for the county. “So we have a whole system that I built for tracking ballots from drop-boxes.”

During a period leading up to an election, voters are allowed to use the drop-boxes, a process that Befus believes adds a layer of credibility for voters wary of sending their ballot through the mail. A few times a day, officials check the boxes, using Esri’s ArcGIS QuickCapture and ArcGIS Survey123 to register the time and leave documented proof of their location. When they return to the election office with ballots, they once again register the time and location.

“We’re more accountable this way,” she said. “If people worry that their ballot wasn’t counted, we can say, ‘well, we were at this drop box at exactly this time, so if you dropped off your ballot it was in there.’”

The convergence of COVID-19 and primary elections has proven so disruptive that some counties are changing the focus of the GIS tools they already use.

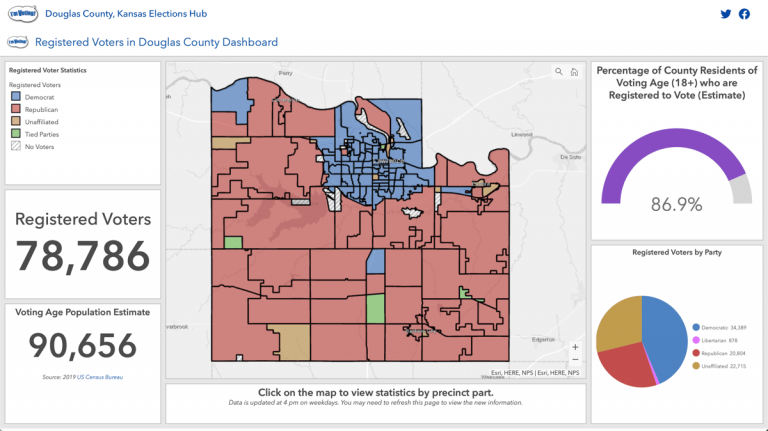

In Douglas County, in northeast Kansas, officials were in the midst of building a GIS-based election hub to coincide with the state’s Democratic primary in May. “We started building it in January and February, when things were still quiet and before we knew what was going down,” said Amy Roust, a GIS analyst who worked on the project.

One of the most prominent features of the hub was a map of polling places. “That’s still the most popular way to vote around here,” Roust explained. “But as we got closer to unveiling it, the decision was made to remove that app altogether. With the pandemic, we had no idea if we were even going to have any in-person voting.”

The team decided to use the hub to display maps of the county, with information regarding the number of registered voters and mail-in ballot requests in each election precinct. The idea, Roust explained, was to give candidates a better sense of the electorate, since the need for social distancing has made door-to-door canvassing a riskier proposition. Organizations involved in voter registration, such as the League of Women Voters, can also benefit from the maps.

As in Maricopa County and others around the country, Douglas County officials also discovered the GIS that drove their maps also helped them change polling station locations to reflect the realities of COVID-19. They could block out nursing homes, and also take schools out of the running—the county had stopped using schools for polling locations after the 2018 shootings at Stoneman Douglas High—while also discovering alternative spaces, such as a local art gallery, that the analysts might otherwise have overlooked.

As the pandemic’s timing coincided with primary season in a major election year, around the country, these mapping tools stood ready for repurposing.

“When we first created the map to figure out where to put polling places, we weren’t thinking specifically about using it for this,” said Bilotta. “But it came in handy right when it needed to.”