June 17, 2025

The cross-country meet in Fulton County, Illinois, was supposed to be just another fall school event—the kind where parents cheer and runners push their personal bests. Chris Helle was there supporting his son Ryan when the unexpected happened: Two adults got into a fistfight.

Helle immediately called 911. “I’m at the cross-country field,” he told the dispatcher. The response caught him off guard: “Where’s that?” He explained that the field was located behind the high school, but he struggled to think of cross streets or the fastest way to get there.

That moment of confusion—a dispatcher unable to locate a specific location on a school site—sparked school mapping standards that have transformed emergency response across Illinois.

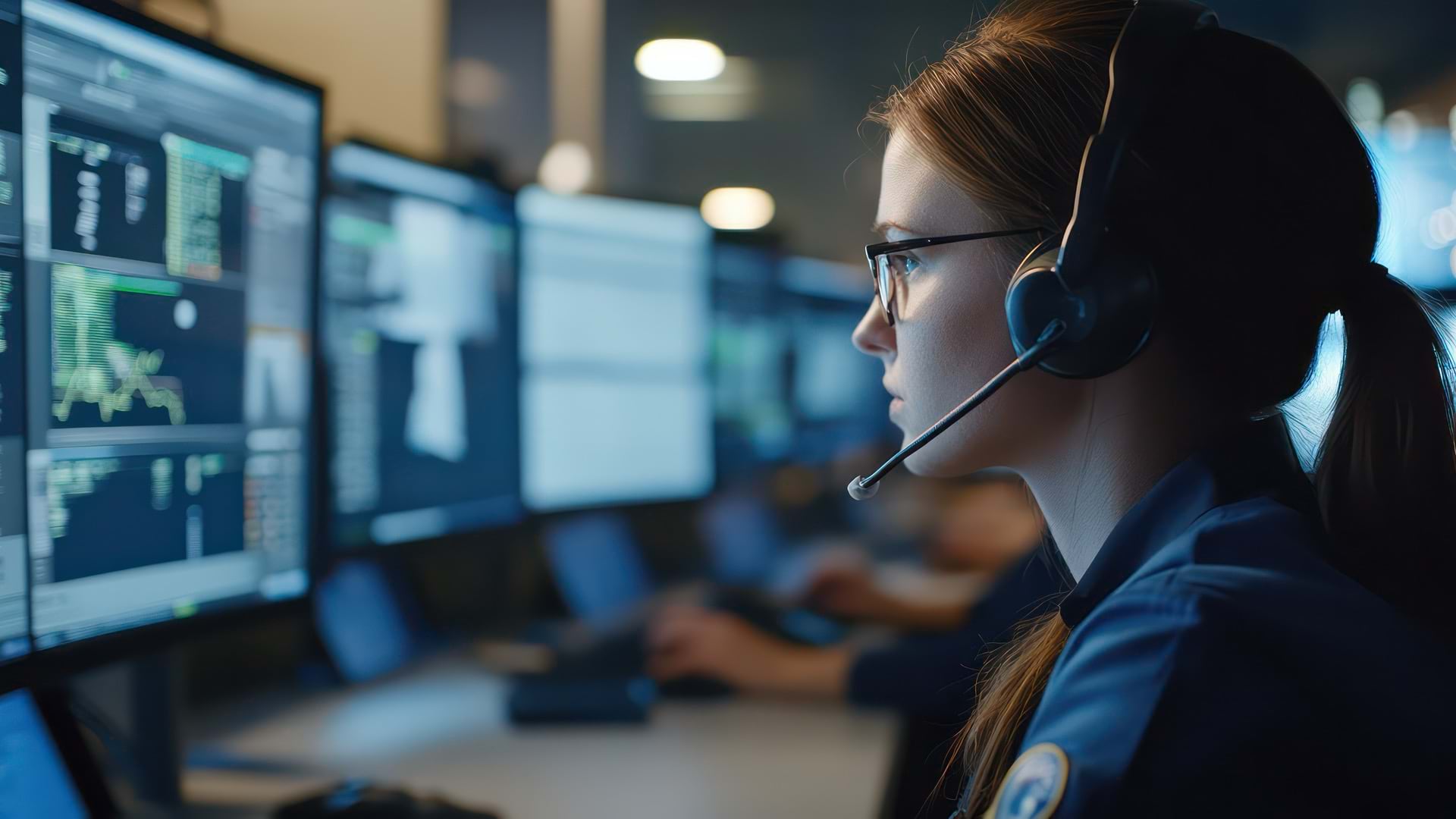

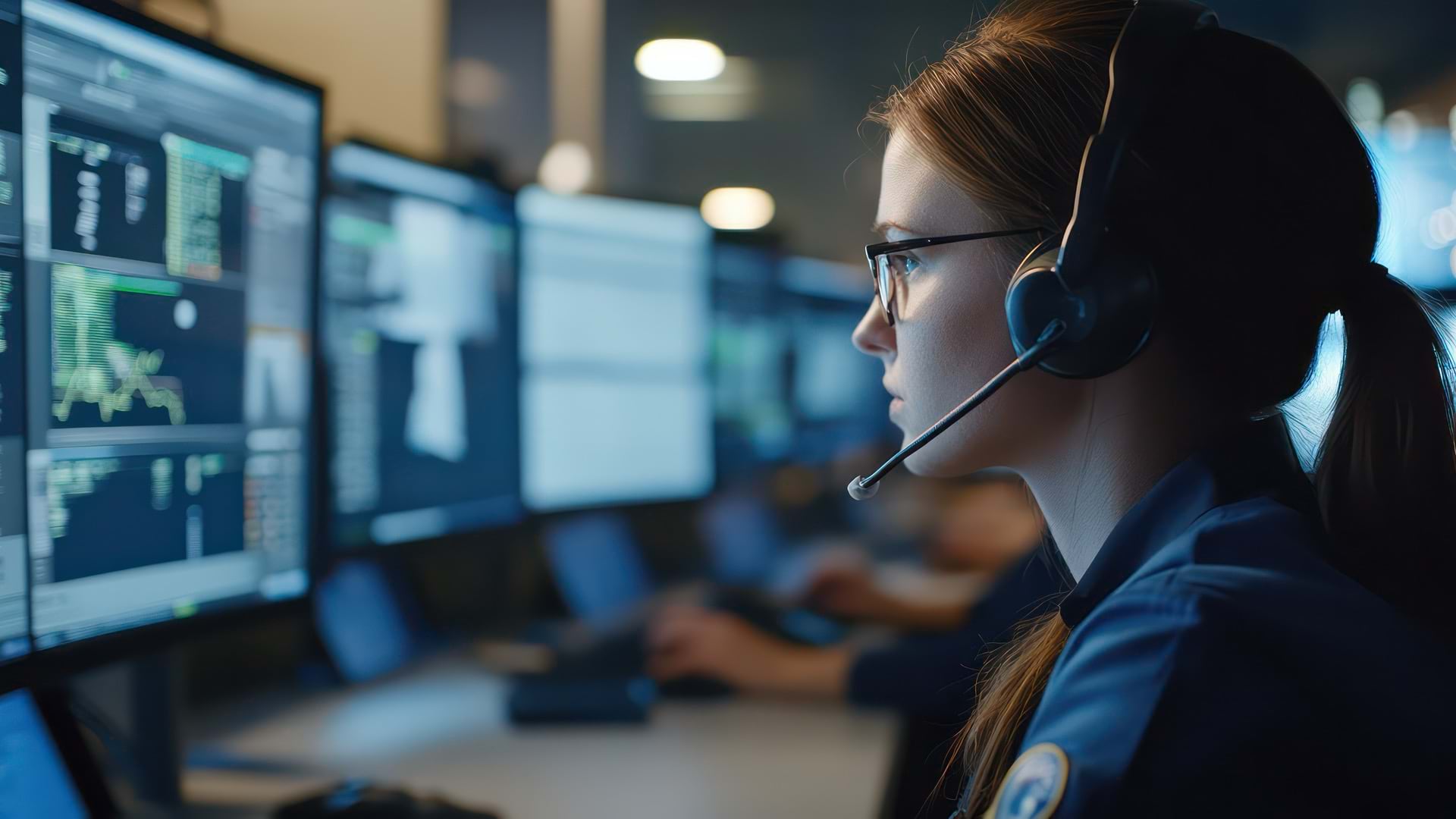

The need for accurate addresses to guide first responders has long been top of mind for Helle, who serves as both emergency management director and 911 coordinator for Fulton County. He and his fellow public safety answering point (PSAP) peers across Illinois have recently rolled out Next Generation 911 (NG911), converting analog systems to digital to improve location validation and emergency call routing.

What seemed like a simple matter—how to quickly find someone in need on school grounds or in a building—revealed a complex challenge emergency responders face daily. Traditional paper maps are often outdated, difficult to read under stress, and impossible to share effectively among agencies responding to the same emergency.

Helle knew the school well, because his kids went to elementary, middle, and high school on the same campus. This event helped him realize how complex navigation directions could be—even for an insider. “When you’re looking at a map, baseball and softball fields look identical,” Helle said. “So if a caller says, I’m near the concession stand, I’m near the football field, at least we’ve got a starting point.”

When he thought about it some more, Helle realized that all PSAP telecommunicators and first responders have a critical gap when it comes to school safety and emergency response. He reached out to two geographic information system (GIS) technology specialists to improve Illinois mapping and addressing systems, enabling faster emergency response.

Phil McCarty, a 911 professional and director of the West Central Joint Dispatch Center, understood this challenge from a different angle. As a former paramedic who started in emergency management services (EMS) in 1995, he knew firsthand how precious time could slip away when responding to a call. “I was lost all the time in Springfield and other places, not only in buildings but on the streets,” McCarty said. “I also understand how important saving time is for the person in distress and for stopping an incident.”

Chad Sperry, director of the GIS Center at Western Illinois University, provided technical expertise and a group of students motivated to work on projects that impact their communities. “The students get hands-on real-world experience, and the harder the problem is, the better it looks on their résumé,” Sperry said.

Helle brought operational expertise from his work with emergency services. McCarty contributed dispatch and EMS experience from managing responses across 1,100 square miles. Sperry brought technical expertise, a workforce, and experience running complex mapping projects.

The trio fueled each other’s curiosity and each lent expertise to come up with a school safety solution that could work anywhere.

The team started with a critical insight: Effective emergency response requires maps that are both extremely detailed and immediately actionable. Traditional paper floor plans, even when available, often sat unused in filing cabinets or were so outdated they became dangerous.

Their solution used a handheld lidar scanner—the same technology that helps self-driving cars “see” their environment—to create precise 3D scans of school interiors. This became a basemap that could be edited in GIS to relate important details.

Every room in each school was identified by a number rather than a teacher’s name. “We don’t want to have a situation where somebody who calls in says, ‘I’m in Mrs. Beoletto’s room,’” Helle said. “Because things change and she may now be teaching on the other side of the school.”

The maps used color coding to distinguish different types of spaces—classrooms in one color, restrooms in another, common areas in a third. The map led to further wayfinding advancements, including door numbers placed not just inside rooms but on exterior windows, allowing responders to identify specific locations even when setting up perimeters outside the building.

Perhaps most importantly, every element of the map became what’s called a “dispatchable location”—meaning emergency dispatchers could route responders to specific points as easily as sending them to a street address. “If a caller says, ‘I’m at the auditorium in Farmington High School,’ we don’t need to put in 108 Lightfoot Road, Farmington, at the high school auditorium. Dispatch can enter Farmington High School auditorium and it will route them right there on the map. We common-named a lot of the more public areas to help callers use more relatable location information which dispatch can also find and use,” Helle said.

These innovations have been tested in a few moments of crisis. The most significant test happened during what initially appeared to be an active shooter situation.

“Someone called 911 and said, ‘I’m going to kill your high school students, I’m headed there now, and I’ve got a gun,’” Helle said. “Approximately two minutes later, he calls back and you can hear shots being fired in the background, and he’s using horribly foul language to describe the students he’s going to kill.”

The incident triggered responses from multiple agencies from across the county—agencies that typically worked outside of this jurisdiction and weren’t familiar with each other’s jurisdictions. “It’s not their community, so they likely didn’t know the schools, and these heroes need to have an immediate understanding of where they are headed,” Helle said.

The indoor mapping system showed all the responders the layout of every building, down to which doors to use.

“It helped coordinate their responses and check off where they had been. They called out every room they cleared. Dispatch and incident command on scene were able to track this in real time,” Helle said. “Indoor mapping becomes an extremely valuable tool when you have agencies who are not familiar with area schools but need to be. This affects law enforcement, EMS, and fire. All of these agencies need to be working with the 911 dispatcher seeing where other units are and using the same room numbers.”

Fortunately, the incident turned out to be a false alarm—criminal harassment known as swatting. But the response revealed how effective the system could be when agencies needed to coordinate quickly across unfamiliar territory.

Another meaningful test came during a medical emergency. A student was choking in an elementary school, and the caller was able to provide a room number where help was needed.

“The room was on the far side of the building near a driveway,” Helle said. “The responding ambulance and fire truck both drove up to that door, went into that doorway, and walked a few feet and found him. If they had used the main entrance, carrying all their heavy gear, it would have likely taken much more time.”

Sperry estimated the system saved five minutes. “I don’t know that it saved a life, but it definitely improved response time, which is how success is measured in emergency response,” he said.

One of the most important components of this effort is standardization—ensuring that all responders, regardless of their home agency, could understand and use the maps effectively.

McCarty explained this concept using an unexpected analogy of the McDonald’s arches. “Why do they look exactly the same around the world? Because they’re communicating to the consumer, this is where you come,” he said. “When you’re communicating to first responders who may be arriving from across the state, standards help because they see the same words and symbols they’re used to.”

One of the most challenging aspects of creating these maps was determining how much information to include. The team realized they could map every fire extinguisher, AED defibrillator device, and electrical outlet, but more information isn’t always better.

“If the map is so busy they can’t find the rooms, then it’s doing more harm than good,” McCarty said. “It turns into white noise, and they start ignoring it. The more standardized we can keep it, and the more streamlined we can keep it, the better chance we have of a positive end result.”

The resulting maps were made to integrate seamlessly with existing emergency response technology. Dispatchers can see the same view as responders in the field, whether they’re using computers in squad cars, tablets in ambulances, or mobile devices carried by individual officers.

“Everybody sees the exact same map,” Helle said. “Everybody sees the exact same points.”

The system also began incorporating new capabilities such as text-to-911, which provides location data that can be pinpointed to specific rooms within mapped buildings. This proved particularly valuable for mental health crises, where a less intrusive response approach is needed.

The success of school mapping naturally led to questions about other complex buildings. The team began exploring applications for hospitals, manufacturing facilities, and municipal buildings like courthouses. Many now have a detailed indoor map.

“Here’s a map of the courthouse,” Helle said, showing how it contains floor plans of all floors. “You could easily have someone call in and say, ‘I’m in the treasurer’s office having chest pains.’ The dispatcher may not know where the office is in that building, but now they do and can see the best way to get there.”

Manufacturing facilities presented unique challenges due to proprietary information and changing floor layouts, but the team sees potential for mapping exterior access points, general building structure, and areas where hazardous materials are kept.

The school mapping project expanded beyond Fulton County thanks to funding from the Illinois NG911 initiative, led by statewide 911 administrator Cindy Barbera-Brelle. “Without Cindy, without her giving us leeway to pilot this, it never would have happened,” Helle said. “Her support, along with the support and leadership of the Fulton County ETSB and work of the team at Western Illinois University, made all this possible.”

The State of Illinois NG911 program provided both funding and a framework for sharing information across the state. This statewide network of PSAP providers allowed the indoor mapping project to scale beyond what any single county could accomplish alone. The project mapped 150 schools initially, with another 400 expressing interest the following year.

The project’s success in rural Illinois highlights an important lesson. While urban areas often have more resources, rural communities sometimes have advantages that enable out-of-the-box thinking.

“Sometimes you can get to a government style where it has to be a certain way, that is, you’re so big you can’t be as nimble,” McCarty said.

The rural setting also provided a manageable scale for testing and refinement.

The involvement of Western Illinois University students added another dimension to the project’s impact. College students who recently left K–12 schools had a fresh understanding of that environment.

“We’ve got 10 students, undergrad and graduate students, that are working on these projects,” Sperry said. “One of our graduate students in particular, Brad Mercer, has really taken a lead role in developing the indoor mapping standards.”

The students gained real-world experience, while contributing essential technical work that made the project sustainable.

The story of rural Illinois’s indoor mapping demonstrates how breakthrough solutions often arise from unexpected combinations: operational expertise, academic resources, student energy, and the freedom to experiment.

“I want to stack the odds in our favor,” McCarty said. “That simple philosophy—using every available tool to improve emergency response—has created a model that’s now influencing emergency preparedness far beyond the cornfields of western Illinois.”

Today, when emergency responders across Illinois receive a call from a school, they’re no longer asking, “Where’s that?” Instead, they’re asking, “Which room?” And in emergencies, that difference measured in seconds and minutes can mean the difference between tragedy and triumph.

The cross-country fistfight that started it all serves as a powerful reminder that innovation often begins with someone asking a simple question: Why isn’t this better? In the case of Chris Helle, Phil McCarty, Chad Sperry, and their teams, that question led to innovation that is now helping protect Illinois students and could help communities across America.

Learn more about how GIS enables a quick response before, during, and after a 911 call.