September 15, 2017

Mosquitoes represent a grave threat to human life. Did you know that these winged vectors rack up almost double the death toll as violent crime and war? Worse yet, the numbers are increasing. With more than 3,500 species and the ability to adapt quickly to new environments, mosquitoes have tremendous potential to spread disease-causing pathogens around the world.

In the past 15 years, we’ve seen examples of mosquito-borne diseases that have caused illness, disability, and death at a pandemic scale. Tens of thousands in the US have suffered serious cases of West Nile virus and Zika virus to name a few. Zika virus also has the terrible potential consequence of causing microcephaly, a type of cranial deformity, in the babies of women infected during their pregnancy. In Florida, where the mosquito threat persists year-round, Zika transmission has increased by 60% since 2004—thanks to the Asian Tiger Mosquito whose larvae hitchhiked inside imported tires filled with pools of water bound for Texas in 1985. The wet conditions brought by Hurricane Irma will exacerbate the problem.

Explosions of mosquito vector populations combined with a highly mobile, ‘pandemically prone’ society has raised the attention of the US and other national governments to investigate the crisis and respond to it with equal measures of brains and brawn. The “brains,” in this case, consist of a location technology platform that helps organize, coordinate, and guide the prevention, surveillance, and control activities of an integrated vector-control plan. The “brawn,” of course, is in the applied tactics used by public health and vector control agencies in their efforts to protect human populations around the world.

GIS is core equipment in the fight.

With mosquitos carrying an assortment of ferocious tropical fevers and uncommon viruses, there’s great interest in adopting and applying modern technology in novel and increasingly effective ways. A geographic information system (GIS) is a key example of such a modern platform.

Geographic thinking, or what we call, The Science of WhereTM, is a natural fit for vector-borne disease surveillance and control. We’re seeing its use increase because GIS technology provides a framework for mapping and modeling that can be easily applied to any vector control operation. A location perspective streamlines and coordinates the workflow and approach from surveillance to response.

The foundation of vector control

There’s no way to kick-start proper reconnaissance without knowing the answers to two fundamental questions:

Without a scientific truth source—datasets and databases—tactical response is impossible. Using GIS to address the mosquito threat begins with surveillance activities. Mosquito surveillance involves predicting where the potentially infected flies will be so that counter-assaults can be strategically targeted.

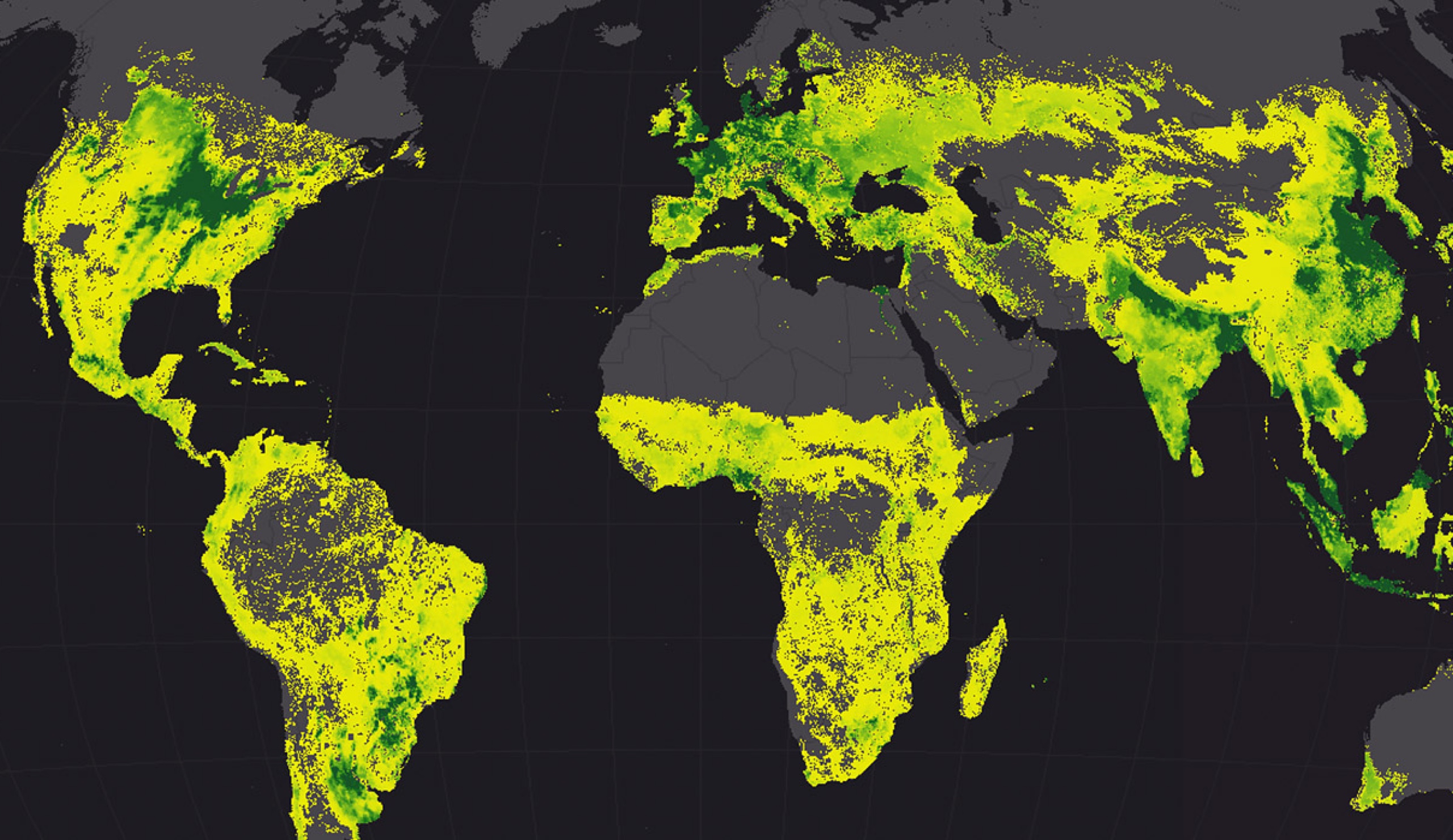

The mosquito is a very delicate fly, restricted by specific biological tolerances. It’s not able to live anywhere it wants. It can’t live on Mt. Rainier, for example, or in Death Valley. Those tolerances are characteristics determined by environmental variables such as elevation, climate, precipitation, and land cover. GIS facilitates prediction of a vector’s preferred environments by visualizing the environmental datasets and databases. Imagine trying to consider all of these factors in a spreadsheet. It would be impossible to detect geographic patterns of habitat suitability.

Engaging the human sensor network

Nowadays, given the spread of smart devices in the population and an appetite for greater engagement in issues that impact us all, crowdsourcing offers a novel supplement to surveillance data in the vector fight. After all, we experience the mosquito bites and see the potential mosquito breeding grounds during our daily commutes and evening walks. But traditional mechanisms don’t necessarily motivate us to report our data. We may get caught up in endless phone loops or struggle to find the right e-mail contact to express our concern. When we do manage to make a report, the precise geographic context may be missing.

The mobile phone provides a fast and easy way to photograph and share our eyewitness accounts. More and more counties, like Atlantic County, New Jersey, use location intelligence to enable citizens to provide the most critical intelligence in the fight through an incident reporter app called Mosquito Service Request. It’s quick work to configure GIS-based incident reporter apps that link to city databases and alert staff in real-time to incidents. This can result in a far more strategic response than sending an e-mail that must go through an extended chain of command before anything is done.

Speaking of real-time surveillance information, there is also the potential to gather intelligence from the community’s passive activity. Social media posts can be collected and mapped, using specific tags, to enhance agency knowledge of potential issues that may not otherwise be reported.

Measured response calms safety concerns.

One can’t discuss the issue of vector control without addressing concerns about the pesticides we use on established vector populations. My first-ever GIS project looked into the effect of aerial pyrethrin pesticide spraying on exposed human populations in Sacramento, California, in 2005. Vector control leadership knew that the treatment was effective against mosquitoes, but it was important to ensure that populations did not suffer harm from pesticide exposure.

Maps oriented and focused that study in a way that raw spreadsheets couldn’t. For example, the flight paths and spraying swaths from planes that spread the treatment were digitally captured and used to develop precise exposure models. Levels of exposure were compared to the addresses of people who visited emergency rooms for any potential complaint related to a pesticide exposure. In the end, we found that the aerial application of pyrethrin pesticides, using the ultra-low volume (ULV) method of spraying, was not associated with any increase in emergency room visits.

I believe that public health pesticide use, when applied to the right areas at the right times, is critical to preventing serious illness from mosquito-borne disease. Using GIS to make those decisions, while also continually monitoring for any potential adverse effects provides people with the dual benefit of reduced risk and safe practices.

Rapid response reduces risk of disease.

Vector control agencies empowered by a location intelligence platform make quick sense of prediction and surveillance information to reduce vector transmission. Such responders can streamline their regular workflows with location intelligence.

Here are just a few parts of the workflow that can be made more efficient

A location-driven approach to vector-borne disease surveillance amplifies counter response and gives us strategic edge in the war. With record rainfall and flooding in Texas and Florida, it’s hard not to think about new mosquito hatcheries causing harm if left unreported. Cities that give the power of surveillance to residents gain important allies in the fight.

Learn more about managing mosquito populations and combat any vector-borne disease that comes your way.