February 18, 2025

England Prioritizes Nature in Development, with Maps Guiding Biodiversity Gains

A bold new initiative, dubbed Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG), requires land developers in England to create 10 percent more biodiversity than was there before the land was developed. To plan, measure, and track projects will take a modern mix of science and technology.

“Development is not just going to be nature neutral. It will be legally required to be nature positive. And this is a huge shift for both the natural environment and our own as well,” Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, said in a recent Esri webinar.

If a developer cuts down trees on their project site, for example, they must make up for that tree loss—by planting trees or creating other habitat somewhere else, on site or off-site—plus 10 percent more. The 10 percent gain will be measured by quantifying standardized units of biodiversity net gain (BNG), based on a habitat’s size, quality, location, and type—both before and after development.

Developers, landowners, and land regulators will use geographic information system (GIS) technology for making and data management to document habitat areas and help measure BNG units. Regulators will also rely on GIS to manage a marketplace for habitat restoration areas and landowners will use it to monitor habitat over time.

Since 1970, species in the UK have declined by 19 percent. One in six species is threatened with extinction, according to a 2023 report produced by Natural England. This new initiative could turn back this dramatic biodiversity decline and bring new vitality to the UK.

Understanding What’s Where

Adherence to BNG legislation typically begins with an assessment. Developers and landowners first need to inventory the value of the nature on their land. This includes the habitats on a site and their conditions, said Andy Wilkins, a senior GIS consultant with engineering firm Mott MacDonald.

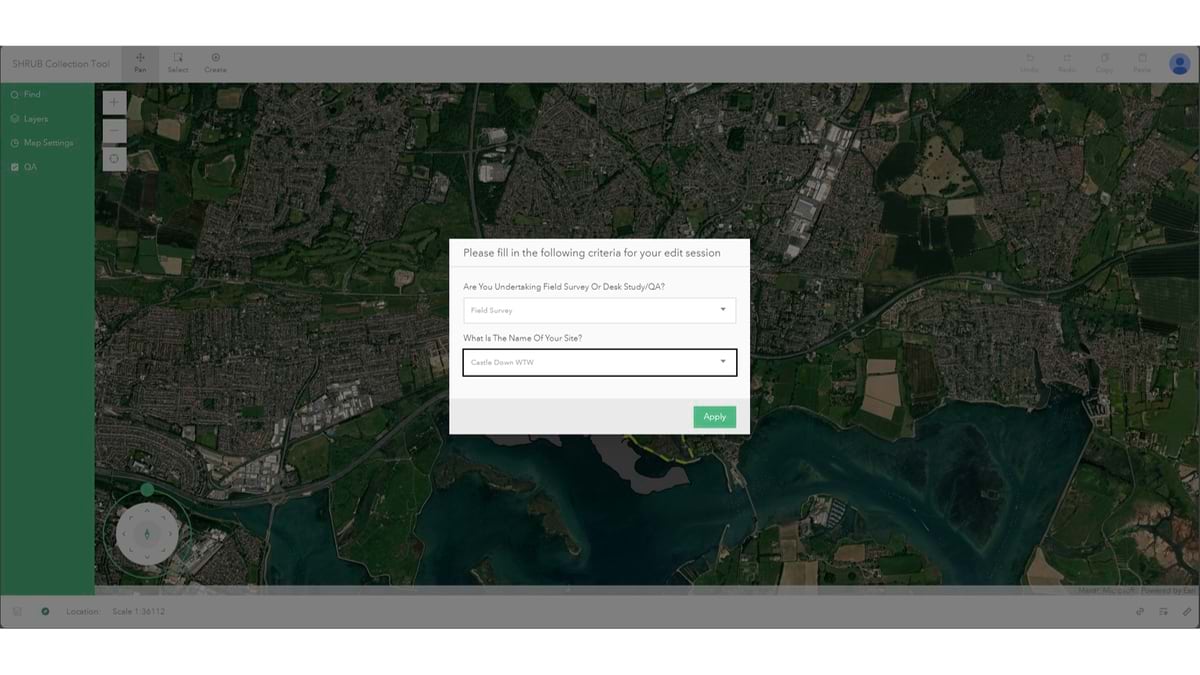

The firm developed a habitat data collection application, containing tools to enhance efficiency and accuracy within the surveying process and to help client assess habitats, using a solution from Esri UK called Sweet for ArcGIS. “We save time, both for the ecologist and the client,” Wilkins said.

For government regulators, the ensuing deluge of data can be onerous. “Applicants are now required to tell us about every square meter of habitat on their site, and then demonstrate to us, in detail, how they’re going to increase that by 10 percent,” said Chris Cole, senior planning policy officer with East Riding of Yorkshire Council.

With 40 planning officers and just three ecologists, Cole said there is a huge need for “help making quick and effective evidence-based decisions.”

The council considers about 2,500 development applications annually. Of those, Cole estimates about 1,000—including major developments, small developments, and infrastructure projects—will require consideration of biodiversity net gain. Exemptions from the new law include applications from homeowners making simple additions to their home or properties, developers building a small number of custom homes on sites less than a half hectare, and projects involving land needed for high-speed rail expansions.

The visualization and analysis tools in GIS maps are already helping East Riding of Yorkshire Council planning officers see available habitats and where applicants are proposing to preserve or create other habitats.

Next, the council hopes to create an environmental digital twin—a living online map that planning officers can use to record which habitats are being restored or created, validate applications, identify nearby constraints, and report on gains and losses in habitat types.

Measuring the Impact and Sharing Data

In another region of the UK, Hertfordshire County Council assists developers willing to pay for needed BNG units by connecting them to landowners with land ready for biodiversity enhancement or preservation. Landowners fill out an online form built with ArcGIS Survey123. Answers to intake questions help assess the size of the land, how many BNG units it may contain, and what types of species might be there.

Many landowners, including those with properties of significant size, started cataloging their BNG habitats in anticipation of the new UK requirement.

The Anglian Water region covers approximately 2.75 million hectares across the UK, and the utility owns about 7,000 hectares of land. Of that, about 2,800 hectares are protected. Emily Dimsey, Anglian’s biodiversity manager, said the utility is voluntarily going beyond delivering the statutory 10 percent through Anglian’s own biodiversity net gain performance commitment.

Teams at the water utility started to track its voluntary commitment in a spreadsheet in 2020. They quickly discovered this method was time-consuming for extracting needed information and was prone to error. In 2023, they worked with Esri UK to develop a tool hosted in ArcGIS Online that can better track the information for a higher level of confidence in reporting. The teams can now produce reports, collect data on-site about habitat and biodiversity, and manage the end-to-end process of enhancing biodiversity on the utility’s land. Information is shared internally with management and externally with stakeholders.

“We now have a single point of truth for our biodiversity net gain data,” Dimsey said.

Helping Nature Flourish

Designers are also using GIS to create project plans that enhance biodiversity. They can model and see the location-specific impact of nature-based solutions, such as planting trees or expanding wetlands to manage floodwaters.

As Lara Salam from Oxygen Conservation put it, “We’re kind of hoping for this messier, more exciting landscape that’s going to provide a greater variety of habitat and plant species.”

Oxygen Conservation, which buys and protects tens of thousands of hectares of land across the UK, starts each of its projects with a habitat survey and assessment of its BNG units. Seeing it all on a map helps the organization better understand where disconnected habitats might be joined, or where to prioritize efforts to add wetlands, woodlands, or scrub.

On much of the land it manages, the organization is working on river restoration that may ultimately help diminish one of the UK’s biggest environmental threats: flooding.

“We like to use the term ‘re-wiggling’ for the rivers, turning them from straight lines—where the water just flows very rapidly through and potentially can go on and flood downstream—to having curves; to having trees which can soak up some water; having areas where the water moves faster [or] where the water moves more slowly; [and] wetland areas,” Salam said.

The result does more than rewild habitat. It can mitigate flooding and the ensuing damage to homes.

“Nature is an incredible engineer,” she said.

Learn more about how GIS protects biodiversity and puts nature on a path to recovery.

Related articles

-

February 27, 2024 |

February 27, 2024 |David Gadsden |Conservation -

January 28, 2025 |

January 28, 2025 |Brooks Patrick |Urban Planning Digital Twin Technology Drives Nottingham's City Center Renewal

-

January 14, 2025 | Multiple Authors |

January 14, 2025 | Multiple Authors |Resilience Restoration Project Builds Climate Resilience in the San Francisco Bay