We don't want to gentrify or displace people. We want to help people be better where they are, because that's where they want to be.

December 10, 2019

Cletus Cashman, a World War II veteran who has lived and worked his whole life in the North End neighborhood of Dubuque, Iowa, spoke of the years he spent bailing out his basement whenever there was a big rain.

“I’d get up at all hours, 1, 2, 3, 4 o’clock—and stay down there until I got it under control,” he related in a video interview from the City of Dubuque. “I’m a stubborn old Irishman, and a Marine, and I never give up on anything.”

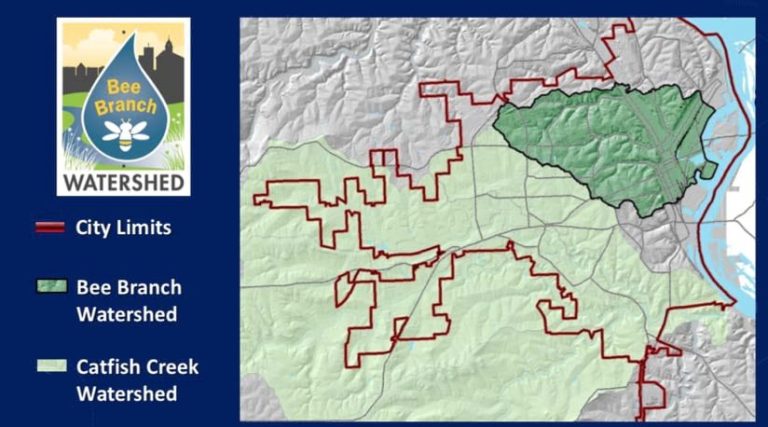

Across decades, he logged hours of cleanup work through anxious nights as he and his neighbors dealt with undersized storm sewers not large enough to handle even a moderate rain event. Dubuque’s steep slopes and bluffs shed water quickly from the west to the east into flat areas adjacent to the Mississippi River. As a result of increasingly intense and localized rainstorms, devastating flash flooding became a recurring problem.

“We get a lot more rain than when I was a kid,” said Nikki Rosemeyer, geographic information system (GIS) coordinator/analyst with the City of Dubuque. “We had six inches of rain in one storm this summer. If we get an inch and a half of rain, you see a river two-feet-deep flowing through the streets of our downtown.”

As Dubuque expanded to higher ground away from the Mississippi River, the problem worsened. Recurring property damage from frequent flooding prevented homeowners from building equity. During the five-year period from 2005 to 2009 when the assessed value of commercial property in Dubuque increased by 39 percent, it decreased by 6 percent in the flood-prone area.

Initially the floods affected only basements, but with growing development and climate change, the magnitude and frequency of flooding increased.

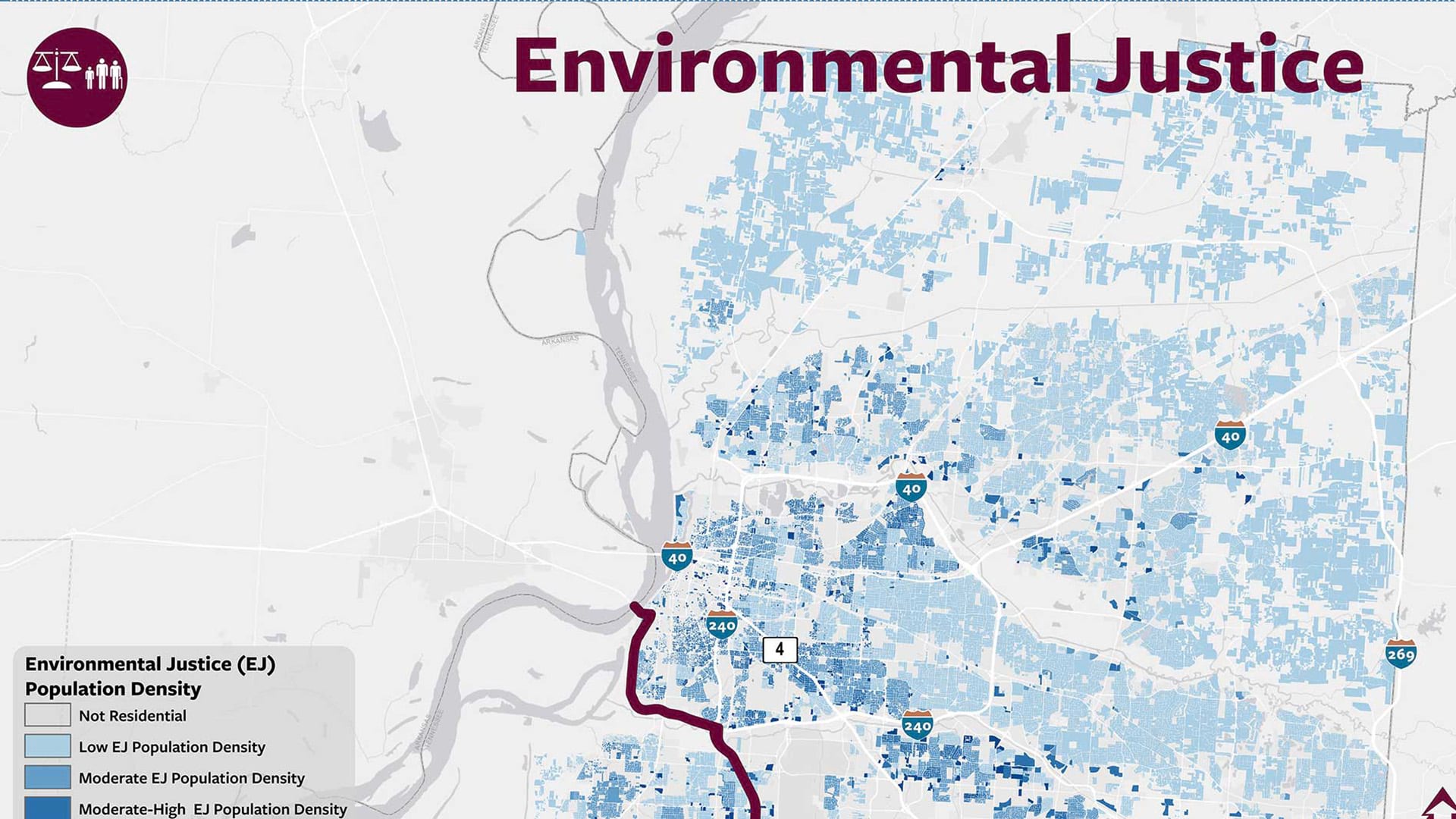

Dubuque has a series of limestone bluffs above its low-lying downtown. Rosemeyer imported lidar data into GIS to visualize the city in 3D and identify the drainage basin causing stormwater runoff problems.

“There are a few different funnels that force a lot of water at a very high rate of speed through residential streets,” Rosemeyer said.

Six presidential disaster declarations were declared between 1999 and 2011 when repeated flooding caused an estimated $70 million in damages to public and private property. It became clear that something needed to be done because people were suffering.

The city applied for grants to mitigate the severe and frequent flash flooding.

“We spent probably 15 years trying to put funding together for the storm water problem, but that doesn’t help the folks in the homes that have been getting flooded for the last 50 years,” said Sharon Gaul, grants project manager for the city’s housing and community development department. “We decided to address both the public infrastructure and the housing structure.”

The Iowa Economic Development Authority received a $96-million-dollar Community Development Block Grant through the National Disaster Resilience Competition funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development and Rockefeller Foundation. Dubuque was one of nine watersheds to receive Iowa Watershed Approach funds, with $23.1 million for infrastructure improvements and $8.4 million for housing improvements.

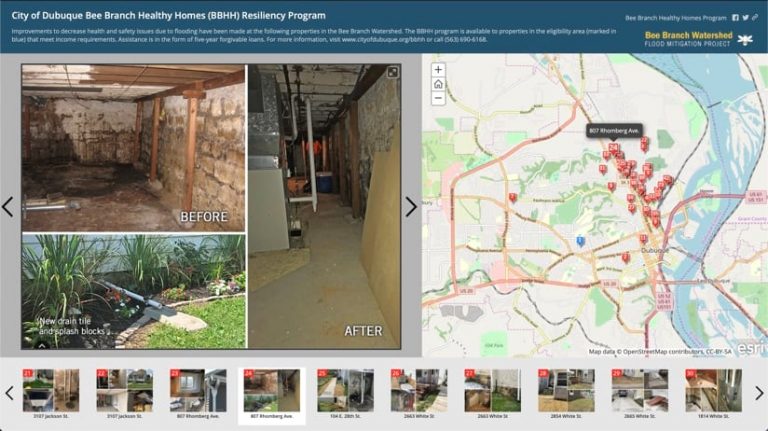

By the end of June 2021, the city will have completed 275 housing unit restorations and three major storm water improvements for the multi-phase work of the Bee Branch Watershed Flood Mitigation Project and the Bee Branch Healthy Homes Project. The flood mitigation project has been under way since 2003 and the homes project since 2016.

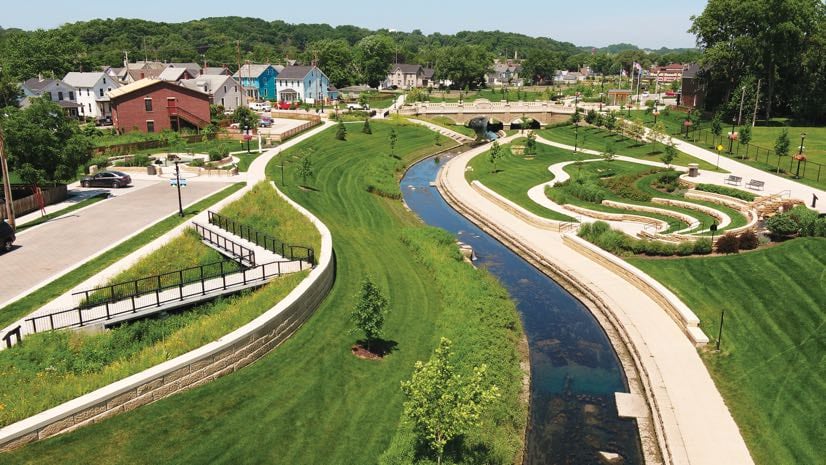

The city uncovered and restored an eight-block stretch of the creek, which required the purchase of more than 100 properties.

“It’s a beautiful waterway and park now,” Rosemeyer said. “It has playground equipment, a garden, and an amphitheater. When it rains, the creek rises out of the channel and fills the green space, keeping water away from homes. It’s unfortunate we had to tear down all those houses, but we needed a safe way to channel storm water through the neighborhood.”

For the 275 refurbished homes, crews working for the city applied a mix of strategies that include repairs to foundations and basement windows, adding sump pumps and perimeter drains, installing gutters and downspouts, replacing furnaces and water heaters, and improving yard drainage with landscaping and soil modifications. They also remove mold, mildew, lead paint, and asbestos from homes.

The infrastructure improvements encompass the major expansion of three culverts that drain into the uncovered, or daylighted, creek, including the culvert under the railroad, which was damaged during the 2011 flood.

While these projects address the hard infrastructure of homes and stormwater channels, the healthy homes effort also addresses the soft infrastructure of community services.

“We look at resiliency as a triangle, addressing the public infrastructure in the street, the housing structure, and the social situation of the family or occupant to identify barriers to success in their lives,” Gaul said.

Social workers from the Visiting Nurse Association in Dubuque took on the social resilience aspect of the projects, visiting with families during home refurbishment and after completion to address any underlying health and welfare issues.

“We’re in their life for 6 to 18 months from application, verification, inspection, bidding, and construction,” Gaul said. “Then we do follow-up visits at 6 and 12 months, working to make a positive outcome to make sure each person or family is resilient, thereby creating a more resilient neighborhood and community.”

The city collected data for all aspects of the projects and imported it into GIS to visualize, analyze, and monitor progress on all fronts.

“We wanted to collect all the information related to the people who were living in each house to determine if they had health problems, if they had asthma issues, if there was mold in the house,” Rosemeyer said.

We don't want to gentrify or displace people. We want to help people be better where they are, because that's where they want to be.

Every single contact was entered in the GIS to record all the work that was done and all the issues that were discussed with residents.

“Some houses have dozens of visits, because the social workers got them connected to the local community college for classes or training for jobs, or to the food pantry, or Goodwill for furniture or clothes, or something from the school district,” Rosemeyer said. “I’m proud of the social workers because they are so involved and so caring.”

The work on these projects has shifted the thinking on all infrastructure improvements in the city, motivating officials to look at who’s impacted and how.

“We don’t want to gentrify or displace people,” Rosemeyer said. “We want to help people be better where they are, because that’s where they want to be.”

The work spanned many different departments in the city, from public works, to health, and planning.

“These projects helped each department learn what the other departments’ concerns are,” said Rosemeyer. “I feel like I do my job a lot better because I know where people are coming from and what they need.”

They also delivered hope for the city’s more vulnerable citizens.

In 2018, Cletus Cashman’s home was modernized. His kids rest much easier knowing their 90-year-old father isn’t down in the basement bailing water during dark and stormy nights.

“This is going to be good for the future of anybody on the North End,” Cashman said. “We lost a lot of stuff over the years, but we’re still here.”