June 4, 2020

By Maryam Rabiee

While geospatial data and technology are helping governments worldwide answer critical COVID-19 questions, each country deals with unique but related constraints that impact response efforts. Many world leaders are forging partnerships and creating collaborative strategies to gather data and analysis to address their constraints and deliver data-driven responses.

This work builds on a 2015 commitment from nearly 200 countries to strengthen resilience to environmental, social, and economic challenges—outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals, the Sendai Framework, and the Paris Climate Agreement.

Five years later, the world confronts a devastating pandemic that could significantly hinder these efforts and alter strategies moving forward.

Before an agency or government can act, it needs accurate information about population count, movement, and accessibility to essential services. But, gathering robust data during a pandemic is no easy feat.

Several sources for global population data help fill in the gaps. The Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (TReNDS), part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network, prepared a recent report detailing data resources that are essential to estimating impacts in times of natural disaster and crisis.

Data that’s based on location, or geospatial, along with technology, including a geographic information system (GIS) play a key role in preparedness and response at local and national levels.

Hindered by insufficient testing, economic sanctions, and inadequate health infrastructures, the available data for COVID-19 cases only covers a fraction of what is happening on the ground. Leaders are rapidly trying to curate datasets that can help assess the situation with more precision. Here we explore the pandemic response work of four organizations to learn more about their pandemic response efforts as well as the wide range of data requirements, and challenges related to policy or technology.

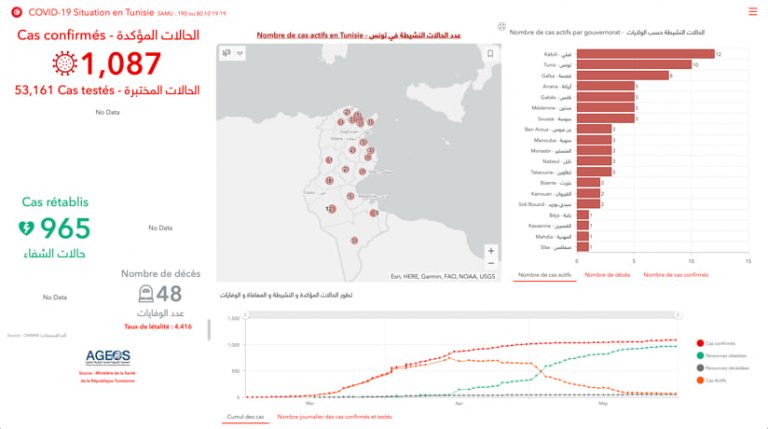

In Tunisia, the Ministry of Public Health built a georeferenced database of hospital bed capacity, necessary medical equipment (including functional respirators and monitors, syringe pumps, and personal protective equipment), and the number of corresponding medical staff. The team worked with Esri distributor, Graphtech, and the African Association for Geospatial Development (AGEOS) to create maps for real-time monitoring of resources, featured on the Tunisian Ministry of Public Health’s website. They also created maps to connect residents with essential services.

“We deployed initiatives for local communities to organize local aid between people, service providers and volunteers, and social NGOs based on location and type of needed services,” said Omar Gaafar, Disaster Response Program lead at Graphtech.

The integration of geospatial databases and maps in the ministry’s COVID-19 response plan was not straightforward for Graphtech and AGEOS. They worked together to show Ministry leaders what could be accomplished with GIS, especially the ability to translate data into easily shareable visuals. Ministry leaders were hesitant to share data for the maps and dashboards until they understood the functionality of GIS platforms.

Despite these challenges, the Graphtech and AGEOS team successfully delivered GIS applications to support the Ministry of Health’s COVID-19 response efforts, improving responsiveness for all stakeholders.

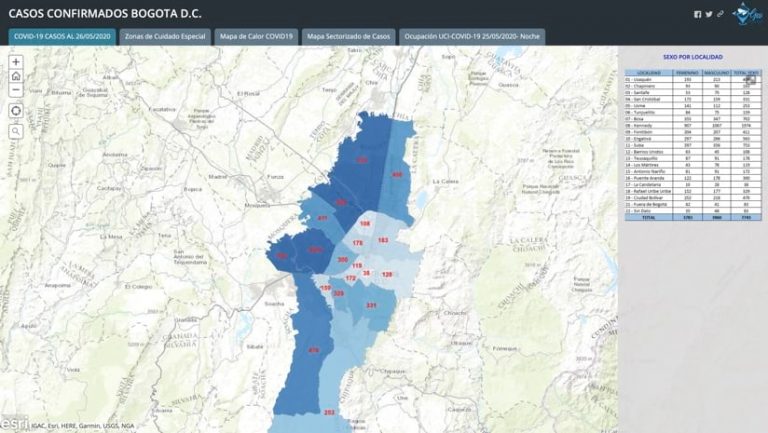

In Colombia, representatives from Cepei, a think tank working directly with national statistics offices, found the majority of reported COVID-19 cases in urban areas. Data on the number of infected individuals, deaths, and other health statistics in Colombian cities is georeferenced, making it easier to map and analyze. Unfortunately, local governments in rural areas lack access to the data and tools necessary for identifying vulnerable populations and responding in real time.

Despite the information gap between urban and rural areas, groups are working together to apply geospatial capabilities for better preparedness and planning across the country. Staff at Cepei, for instance, are reviewing the COVID-19 impact on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), working closely with the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

“The lockdown has caused an interconnected chain of events: school closures have limited students’ access to education, school meals, and other services, impacting measures related to the SDGs of poverty, hunger, and a quality education,” said Fredy Rodríguez, data coordinator at Cepei.

Staff at Cepei refer to an interactive map created by ECLAC that makes public policies from 33 countries available from Latin American and Caribbean regions to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, such as restrictions in movement and school closures.

The Mayor’s office in Bogotá is monitoring the spread of the virus in each neighborhood based on movement in the city, travel history, and contact tracing. The data, disaggregated by age and sex, are presented on a map to encourage transparency in evolving policies and regulations.

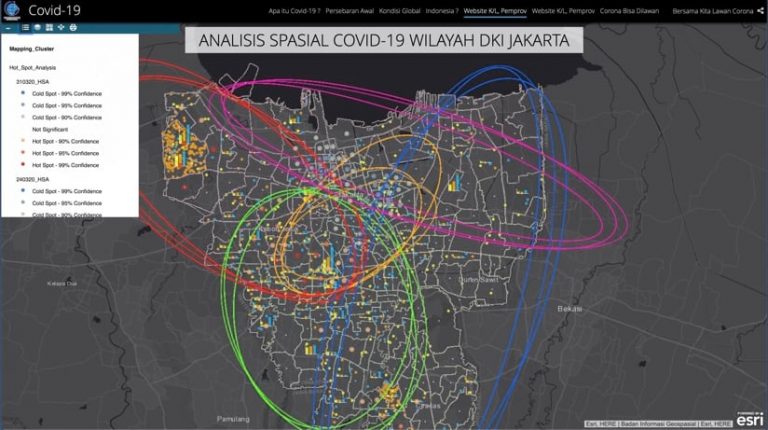

In Indonesia, staff at geospatial agency Badan Informasi Geospatial (BIG) report strong spatial analysis and statistical capabilities with daily reports available on the BIG website. But insufficient real-time data, due to reporting lags, affects the outcomes of their GIS models and analysis. BIG staff also say they need a data framework that can ensure accuracy and effectiveness for their analysis. “How can we fully distribute services to the people when we can’t guarantee the accuracy of the data we have to the public?” said Ferrari Pinem, head of the disaster mapping division at BIG.

Another factor in BIG’s work is that the local and the central government may have different approaches and tools for policy making, generating different data and outcomes. Although Indonesia has already launched the one data policy, it seems the stakeholders should be more committed to implement the policy. “We are still trying to be transparent about georeferenced data and create an open system while protecting the privacy of COVID-19 patients and affected individuals,” said Ratna Sari Dewi, senior researcher at BIG. The Lack of a standard framework in data collections will affect the effectiveness of COVID-19 response. Without cohesive policies or access to geospatial and health data, it’s difficult to determine how effective certain measures are for keeping communities safe.

The pandemic has underscored the importance of accurate, timely, and comprehensive data not only to overcome COVID-19, but also to advance global sustainability agendas. As regions and agencies band together, they can avoid duplicate efforts and ensure resources are directed toward data gaps.

For example, representatives from ECLAC are trying to create a space where geospatial information can be used to inform policies and help manage the pandemic across Latin America. They are facing three major challenges: assessing the geospatial capacity in each country in order to contribute the appropriate support and resources; implementing central platforms (such as spatial data infrastructures) to enhance coordination among mapping agencies, health ministries, and other government bodies; and minimizing long-term impacts of the pandemic on critical events such as delays in the collection of 2020 census data.

ECLAC and the United Nations Global Geospatial Information Management for the Americas conducted a survey to identify geospatial gaps and requirements in the context of COVID-19. This effort is raising levels of awareness and understanding about GIS capabilities.

“ECLAC’s encouragement to implement geospatial data and technologies has created an opportunity for countries to showcase geospatial information to a wider audience,” said Álvaro Mauricio Monett Hernandez, regional expert in geospatial information management at ECLAC. “In Chile, for example, the national news outlet displays a geospatial platform during COVID-19 reporting.”

Challenges faced in Latin America, Tunisia, Indonesia, and elsewhere demonstrate a need for more collaborative, cohesive operations using GIS to organize, analyze, visualize, and share crucial data.

As the global pandemic reveals strengths and weaknesses in each nation’s data ecosystem, it presents a chance to work together to rebuild stronger systems and reduce adverse impacts on sustainability plans.

Learn more about how GIS supports sustainable development.

Maryam Rabiee

Maryam Rabiee manages the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network’s Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (SDSN TReNDS). Her work focuses on exploring new methods and approaches to strengthen the data ecosystem for sustainable development. Current projects include the POPGRID Data Collaborative, an international community of data providers, users, and sponsors concerned with georeferenced data on population, human settlements and infrastructure, and Data For Now, an initiative that aims to increase the use of robust methods and tools that improve the timeliness, coverage, and quality of SDG data.