July 5, 2018

When 95 percent of imports and exports move by ship, as is the case in the US, keeping ports open is critical to the economy. The US Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps), which maintains the country’s waterways, must wage a constant battle against the forces of nature. Anytime a storm hits, underwater sediment shifts and threatens to make port water too shallow for cargo ships. The Corps dredges these ports, keeping them open for business. Ship captains and harbor pilots rely on this work, along with related updates about port conditions, to avoid getting grounded in the mud.

With the 2016 Panama Canal expansion, the cargo capacity of ships traveling through the important channel nearly tripled. Along with it came an increase to each ship’s draft—the distance between water line and keel that marks the necessary water depth for safe travel. These “New Panamax” ships have a fully loaded draft of nearly 50 feet, placing constraints on navigation that favor the nation’s deep water ports.

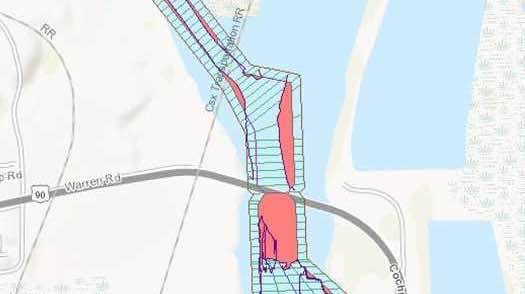

In the deep water Port of Texas City in Galveston Bay, recent storm-related sediment build-up (known as shoaling) reduced the shipping restriction from the typical 45-foot draft to just 41-feet. This four-foot difference had an economic impact to both the port and the industries that rely upon it. The lower draft meant that companies needed to either use smaller ships to ferry cargo into the Gulf of Mexico for loading onto bigger ships or divert their ships to different ports.

The key Brazilian port of Santos experienced similar storm-related restrictions [gated content]. The port estimated that every day a vessel is not operating, ship owners lose between $10,000 and $75,000 per day depending on the size and type of ship. One day of restrictions in Santos collectively costs ship owners $1 million, and this figure doesn’t factor the cost to the port and the overall economic impact to the country’s economy.

Without dredging, many ports would become impassable.

Dredging the Ports

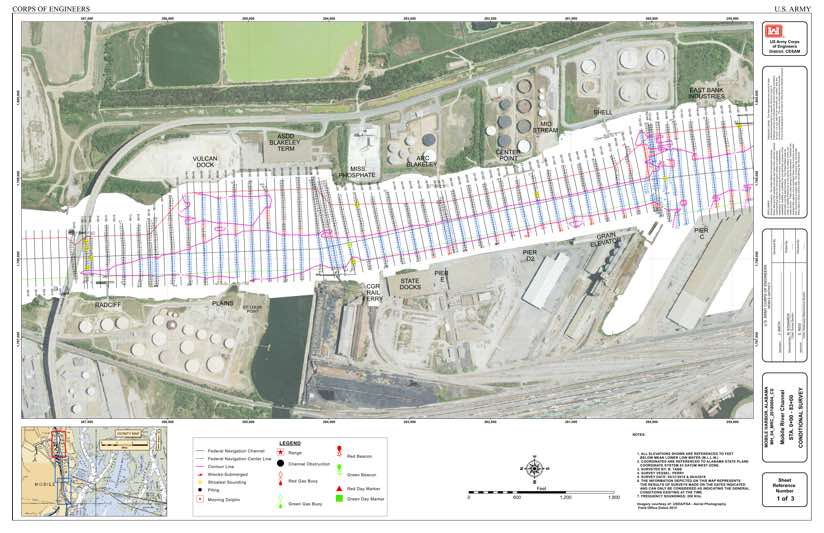

The Corps performs regular maintenance, akin to the paving of roads, in 400 ports and harbors and along 13,000 miles of deep-draft coastal channels and 12,000 miles of shallow-draft inland and intracoastal waterways. Spikes of storm debris add to the Corps workload, resulting in 250 million cubic yards of material dredged from the nation’s waterways yearly.

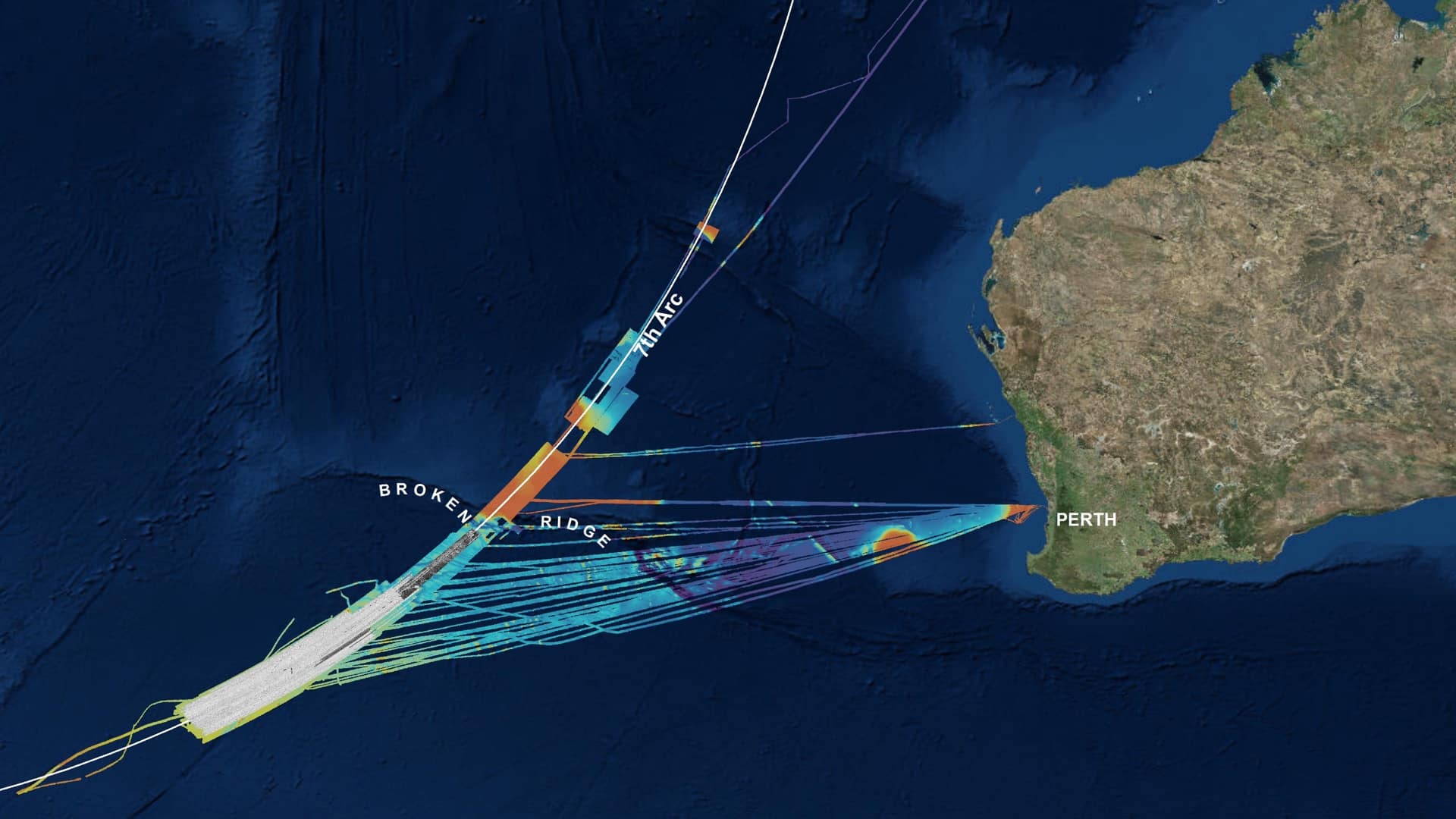

The Corps conducts regular hydrographic surveys across 22 coastal and 16 inland districts to assess channel safety and prioritize dredging needs. Recently they started using an enterprise-wide system, dubbed eHydro, that includes tools and workflows to catalog, organize, and share surveys.

“The Corps is a decentralized organization with districts managing their own programs in their own geographic areas of responsibility,” said Tony Niles, assistant director for Civil Works Research and Development, headquarters, US Army Corps of Engineers. “This structure proves effective for project management, but it poses challenges for pulling together enterprise data.”

eHydro comprises an application and scripts to easily and almost automatically feed the data from each survey into a Corps-wide system.

“We’ve been working to arrive at an enterprise data collection process for 20 years,” Niles said. “We realized this goal by inserting the reporting into existing project workflows—not changing any data collection methods or tools, just changing what they do with the dredging data once the boat is in.”

Free Flow of Information

Each dredging effort is a project, so eHydro acts as a centralized system of projects. It captures the horizontal and vertical dimensions of each dredging project as the work is completed and records surveys periodically conducted to assess current channel conditions.

Since implementing the approach, the Corps has seen marked improvements in the accuracy, consistency, timeliness, and sharing of project information. The streamlined data aggregation allows for automation of regular reports on channel availability and condition.

“Previous to eHydro, channel information was sent to a central location but after it was there a period of time it was stale,” said Mel Littell, engineering technician in the Portland District of the Corps where eHydro originated. “Now, when each district changes something in their channel, they just push a button and it updates the national channel framework ensuring everybody works off the same current data sets.”

The internal data sharing was a big advancement, but the full benefit comes from sharing to all the various stakeholders through the Corps Navigation Portal. Now information can flow to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to update the nation’s navigational charts.

“The Corps data is by far the biggest outside source of data that NOAA uses in its nautical charts,” said Clint Padgett, chief, Spatial Data Branch, the Mobile District of the Corps. “In the past they had to go to every district and normalize data provided in more than 20 different formats. Now, they just consume our data through a web service.”

Knowing the Channels

Dredging projects are constantly in backlog given the workload plus time and budget constraints.

“If we’re going to maintain all of our 25,000 miles of channels to authorized dimensions 100 percent of the time, we’d need billions more dollars,” Padgett said. “We know that we’ll never get that level of funding, so we work to manage impacts with the budgets that we have.”

This means a constant weighing of tradeoffs for the Corps. If one channel is authorized at a 35-foot depth and it’s only 32 feet, the Corps has to balance the $5 million additional cost to get the channel to that depth against other projects. In some cases, it’s more impactful to dredge a deep-water port from 40-feet to 45-feet to accommodate today’s larger ships.

Now, the Corps has a means for evidence-based decisions to clearly compare present channel conditions and prioritize dredging funds against the impacts to commercial shipping.

“We can get surveys turned around quicker to know about changing conditions and prioritize trouble areas,” Littell said.

The Corps works in close coordination with cargo pilots who move large vessels—a group that’s become a big consumer of Corps data even though the Corps doesn’t produce navigation charts on coastal deep-draft harbors. Pilots count on the Corps to know the latest channel conditions.

“The Columbia River Pilots Association depends heavily on this information,” Littell said. “We meet once a month with the pilots to address their concerns. We go over every single chart and look at where material is building up and where we should do more maintenance.”

Over the next 20 years, the volume of cargo traveling by container ships is projected to increase by 65 percent, according to McKinsey & Company. With demand at ports and waterways on a steady rise, the Corps’ streamlined data sharing efforts have an increasing impact on the flow of commerce.

Visit the Corps’ Operations Dashboard to see the number of surveys and survey extents across the country. Visit ArcGIS for Maritime to learn more about navigational charting.