August 18, 2020 |

November 2, 2020

Climate change and the novel coronavirus are adding to already difficult wildlife conservation challenges and harsh human conditions across conflict zones in Africa. In response, local ranger teams with Chengeta Wildlife are finding new ways to approach threats to human and wildlife sustainability.

“In places like the Central African Republic, the people literally live hand to mouth,” said Rory Young, president and cofounder of Chengeta Wildlife, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting and promoting harmony between humans and nature. “The work you do feeds you tonight or tomorrow. If they are in lockdown and can’t work, they are literally starving.”

The nexus between poverty, poaching, and wildlife trafficking causes ongoing problems across Africa and around the world. According to a recent report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, the annual illicit income generated by elephant ivory is estimated at US$400 million. Poachers get just a small fraction of that take, but in places of high poverty the income and the meat provide motivation for opportunistic killing. Often this takes place outside parks where there’s less risk of detection and a dire need for food.

“I go into dead forests where there isn’t a living thing,” Young said. “People have eaten the birds, the insects, all the termites. I remember seeing these places thriving with wildlife. There is mass slaughter on the ground, and I don’t think that gets conveyed.”

Desperation is a major reason people poach. Networks of criminals are also taking advantage of COVID-19 restrictions that make it difficult for rangers to go on patrol.

Chengeta Wildlife maintains a permanent presence in the Central African Republic, Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Mali, and Burkina Faso—all countries currently experiencing some level of violence.

“We don’t specifically seek out conflict zones,” Young said. “We go where the need is greatest.”

The organization takes an intelligence-driven approach to thwart poaching, training rangers to track and apprehend poachers by anticipating their movements.

“When we deal with a problem in a given area, analytics and actionable intelligence inform our planning, coordination, and execution of missions,” Young said. “Improving the technology allows for improved command and control.”

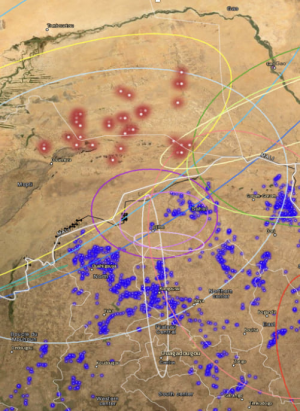

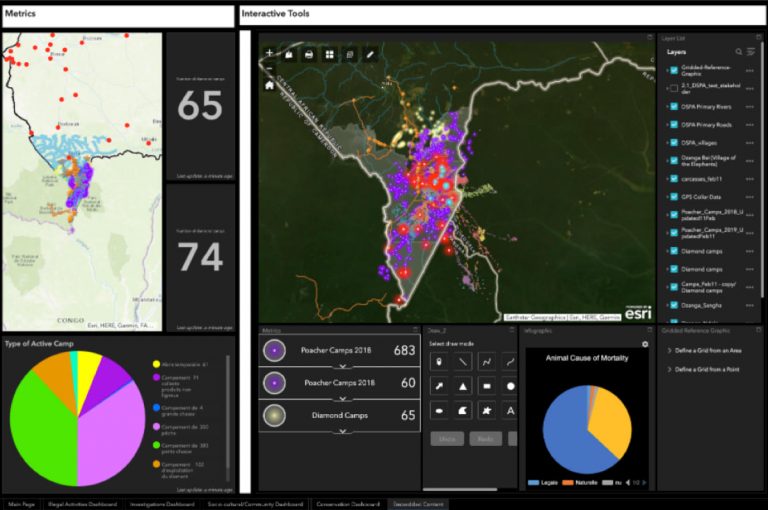

Chengeta Wildlife uses smart maps and apps based on a geographic information system (GIS) to aid rangers and park managers.

“We teach rangers to use GPS and put information on a map to visualize the situation—situational awareness is critical,” Young said. “The rangers are either collecting data or absorbing the analysis, and they pick it up incredibly fast. They have a keen understanding of geography and appreciate the importance of improving that understanding all the time.”

Rangers collect data and share it with the Countering Wildlife Trafficking Institute in Saint Louis, Missouri (see sidebar). There, geospatial intelligence experts combine all the collected information to target poachers, prioritize missions, and provide tactical support.

“These situations are too complex to be understood in any way other than by visualizing via mapping,” Young said. “The better rangers understand their environment, the more they are able to ensure their own safety and succeed in their mission.”

Chengeta Wildlife works in places where there’s fierce competition between humans and wildlife for resources, space, and habitat.

“That’s where the real battle’s being fought,” Young said. “The solution is not just less people or to create more parks. It’s really about understanding the conflict generators.”

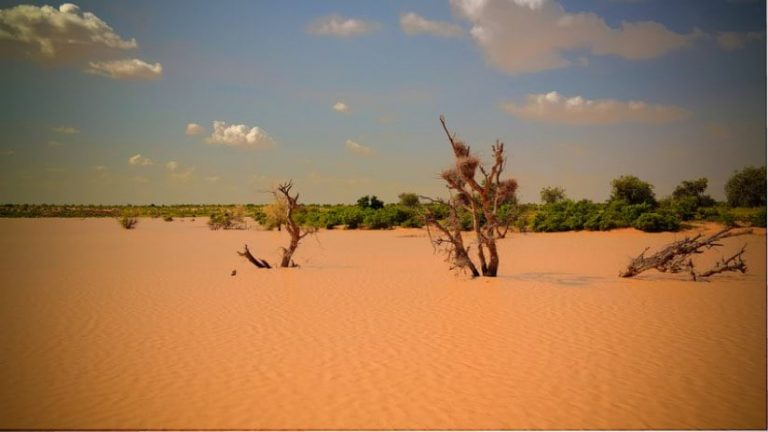

In the Sahel region of Africa, desertification is shrinking arable land. The Fulani nomadic herders have moved south as the desert has grown, putting their cattle in competition with wildlife as well as sedentary ethnic groups that grow crops. Often, these groups have different religions, beliefs, and nationalities.

The Sahel is ground zero for climate change because two completely different environments—rain-free desert and low-rainfall savanna—meet here. The area has seen extreme temperatures, fluctuating rainfall, and decades of drought. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that 80 percent of the land in the region has been degraded, causing more than 30 million people to suffer from severe food insecurity.

“It should be seen as a prophecy,” Young said. “It’s going to happen on a larger scale in more places in the world. When the environment is destroyed, people go hungry and they’re forced to move, putting pressure on someone else.”

Chengeta Wildlife works to understand what’s needed. If the problem is hunger, the answer isn’t necessarily more arable land. The solution might be to teach new farming practices. If the problem is a lack of water, drilling for water or managing the environment to capture runoff during the rainy season may be the answer.

“Our community experts point out that the problem is often not a lack of money, it’s how to manage money and having a place to put it,” Young said. “We try to figure out how to help people so that we can help the wildlife.”

Despite overwhelming challenges, Chengeta Wildlife has had success. It takes a pragmatic approach—determining where there’s need, where people want help, and where the group’s solutions will improve the situation.

“When we take on a project, we really believe we can make a difference, and then we go for it,” Young said.

On one project in the Sahel, Chengeta Wildlife staff are busy training 900 rangers to protect an area of a quarter-million square kilometers. In Mali, staff curtailed the poaching of desert elephants—which had seen a loss of 45 percent of the population from 2015 to 2016—and achieved a zero percent loss by 2019. Now, that region’s elephant population is growing, despite escalating security problems.

Young and others at Chengeta Wildlife are working hard to repeat a pattern of success. They forge partnerships with like-minded organizations and use GIS to understand the movement of elephants and poachers to predict activity at a particular time and place.

“The geospatial analytics is very important to determine where, when, and how we should move to avoid confrontation or conflict,” Young said. “It allows us to disrupt the opportunity—getting there, stopping the poaching, and exfiltrating safely to keep our rangers alive.”

Learn more about how location technology is contributing to conservation efforts.

August 18, 2020 |

March 7, 2018 |

September 4, 2019 |